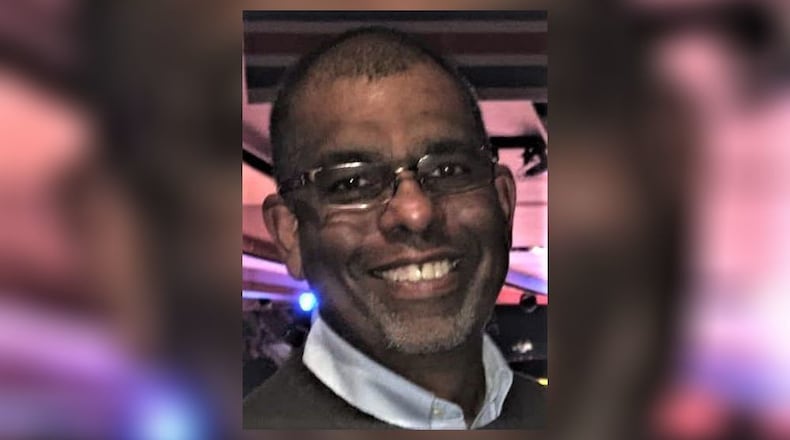

Jones, a Dayton resident, lives and sees the economic strain on people like her. As a single mother of a 5-year-old daughter, she navigates the daily squeeze brought on by rising prices and limited funds. She sees the pain in the faces of the people who visit McKinley United Methodist Church, where she works with two programs that help the needy — a weekly food pantry and Jan’s Closet, which provides free clothes for the poor.

At the pantry, a rainbow coalition of poverty shows up to seek help. Black, White, Latino, homeless, single moms and retirees on social security line up to get a box of food that has gotten smaller over time. Jones said the 60 or so people who come to the pantry each week used to get as much as $250 in food. Now, it’s about half that.

She even sees people with steady, full-time jobs who are so financially stretched they need the groceries to stay afloat.

McKinley is located in the 45402 zip code, one of the poorest in a city in which more than one in four people live in poverty and many of the rest subsist on low incomes.

Single people in the city of Dayton have an average income of about $507 a week, or $26,381 annually, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. In 2000, the per capita income was $15,547, an increase of about 70% in 25 years.

While 70% sounds like a lot, it’s not.

Due to inflation, it would cost $1.85 today to buy what $1 purchased in 2000. That’s an 85% increase. Eggs (+279%), frozen orange juice (+85%), and sugar (+71%) have seen massive increases — since 2019.

When I asked Jones what people don’t understand about how the economy impacts those at the lower end of the financial scale, she said eloquently:

“It’s impossible to thrive or get ahead, with the pay that we get versus how much stuff costs, the taxes that come out, and living expenses. It’s so tough to find a decent apartment that now costs more than a mortgage did 10 years ago.”

She continued: “People think ‘Oh, inflation isn’t that crazy. They need to work harder.’ But the pay has stayed the same since COVID, prices have changed drastically, and jobs are tight. More than anything, I see people my age, millennials, busting their butt to get to the next level to save enough money to get a house so that we don’t have to pay high rent. I hope people will understand that if stuff keeps going up, it’s going to get harder for a lot of people who are either beginning or trying to transition into the next part of their life.”

Donald Trump promised the economy would be the best under his watch. Now, he says Americans will have to undergo some pain before it gets better.

That’s easy for a man with a net worth of more than $4 billion to say. It’s also easy for the country’s billionaires to suck it up and absorb their combined $400 billion in losses since Trump took office. After all, the country’s 800 billionaires have more than $6.2 trillion in wealth, according to Inequity.org.

The pain is far more acute for the poor each week. They’re the ones who were promised a rosy future and have so far been sold a bill of goods.

Jones and the people she serves are the face of the economy, the people who hurt every time eggs go up another dime a dozen. While the administration pays lip service to pain, Jones lives and bears witness to it.

“(At the pantry) I see a mother holding a baby and a baby on her back,” she said, shaking her head and sighing, “What do you do with that?”

Ray Marcano’s column appears on these pages each week.

About the Author