I was excited back in 1976 when President Gerald Ford officially recognized February as Black History Month. He urged the country to “seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of Black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history.”

Instead, the month — which traces its origins back to 1915 — has become marginalized with meaningless recitations of the figures we know, but no meaningful discussions about how history continues to impact Black people today.

We’ll mention Martin Luther King Jr., who has long had a place on the Mt. Rushmore of civil rights icons like Gandhi, Mandela, and Tutu. We’ll talk about George Washington Carver’s work with peanuts. Harriett Tubman’s effort to help enslaved people find freedom via the Underground Railroad always gets a mention, as it should.

Those history lessons, nearly 40 years after Ford’s remarks, have the same impact as repeating that we’ve had two unthinkable world wars, man walked on the moon, and Barack Obama served as the country’s first Black president.

They’re all statements of fact that don’t connect the dots and show that Black people remained shackled by the past.

We might discuss how Black soldiers willingly served their county in WWII. But we won’t discuss how the federal government provided GI Bill benefits to white soldiers but withheld them from Black fighters.

We’ll note that the Fair Housing Act of 1968 prohibited discrimination in the sale and rental of property. We’ll laud it as another stop on the path to equality, but without providing context.

For example, in 1936, the Federal Housing Administration refused to back mortgages in Black neighborhoods or ones near them. Its underwriting manual says neighborhoods with “inharmonious racial groups” made a bad lending risk.

Also, on the housing front, racial covenants prohibited Black people from owning property — homes or land — in a wide swath of neighborhoods in the United States. The Supreme Court made the covenants illegal in 1948, but they remained common through the 1960s — just two generations ago.

Here’s how you connect the dots. As a result of this government-sanctioned discrimination, Black people were restricted to mostly or all-Black neighborhoods with a less valuable housing stock that didn’t appreciate over time. They had a market limited to other Black buyers who didn’t have the means to make improvements and increase the value of their property. As the years progressed, Black people couldn’t take advantage of the number one way Americans build wealth — through their homes.

That’s why, today, the median white household has a net worth of $188,200, nearly eight times that of a Black family ($24,100), according to the Brookings Institution.

I’m not saying that if everyone had an equal chance the income numbers across the board would be closer. No one knows that. But we do know unequivocally that systematic racism held back Black people.

Don’t believe me. Look at the federal government’s policies and words.

We need to have these discussions connecting the dots in a meaningful way, despite efforts like Florida’s law that makes it harder to talk about concepts related to race. These laws came about following hysteria that schools and workplaces would shame white people with the ills of the past.

The shame rests in hiding the truth. No one individual, regardless of race, bares blame for the country’s systematic discrimination of the past. But we’re all responsible for what happens now.

That starts with connecting the dots, understanding how the past impacts today, and why Black people still face a tough road to equality. I’ll get excited about Black History Month again when that happens.

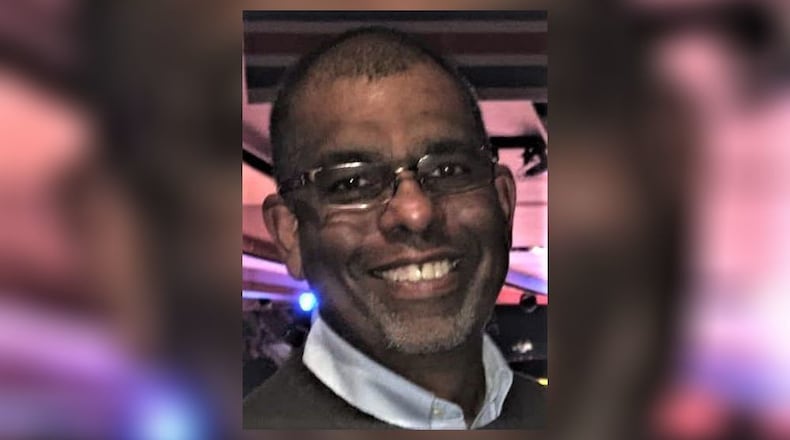

Ray Marcano’s column appears on these pages each Sunday. He can be reached at raymarcanoddn@gmail.com

About the Author