Ranked choice can be complicated, but it’s also a far better system than most-often used plurality voting.

In ranked-choice voting (RCV), voters have the option to cast ballots for candidates in order of preference. (They also have the option to cast one vote for one person and not for anyone else.)

For example, if there are five candidates on the ballot, each can be ranked one through five. If any candidate gets 50% (plus one) of the vote he or she wins. But if no candidate reaches that threshold, ranked choice comes into play. The candidate with the fewest first place is eliminated, and his second-place votes get redistributed to his supporters’ second choice.

Once you get past the confusion, you can see the advantages.

Under ranked-choice, the winner will always have more than 50% of the vote, indicating wider support among constituents. Under the current system, it’s not unusual for candidates to win an election with less — sometimes far less — than 50%.

Research shows that municipalities that use ranked choice are less likely to use negative campaigning and focus on the issues. That’s because a strong base of support isn’t enough. Candidates have to appeal to a wider swatch (i.e. more moderate) voters to get over the 50% threshold.

That’s a big change from where we are today.

Political parties and special interests dislike RCV because it makes it harder for their candidates to get elected. Look what happened in New York City. Eric Adams, a moderate pro-police Democrat, narrowly won the mayor’s office, and Progressives cried foul, not because there was anything wrong with the system, but because they thought their candidate had a better shot in a one-on-one matchup.

Lawmakers dislike it so much they want to stop it at all costs. In Ohio, Sen. Theresa Gavarone, R-Bowling Green, and Sen. Bill DeMora, D-Columbus, want to prohibit RCV and withhold state funds from any municipality that uses it.

Bipartisan support to thwart a better system? Who’da thunk it? You know it’s a good idea when both major parties oppose an effort to change elections for the better and threaten municipalities in the process.

But expense is a more difficult roadblock to overcome, as Riverside found out. Mayor Pete J. Williams said, in an email, that voting machines would have to be altered to accept RCV ballots and that change would be pricey.

More than 60 jurisdictions now use RCV, mostly for local races (mayor, city council, etc). Alaska uses it most aggressively in most contests, including its state legislature as well as U.S. House and Senate races.

Williams said, “The aspirational hopes behind RCV ... that strives for less devise elections, works to curb harsh rhetoric, and should increase opportunity at the ballot are certainly worthy endeavors…”

He’s right. Ranked choice voting is the future. Maybe Riverside can lead the way.

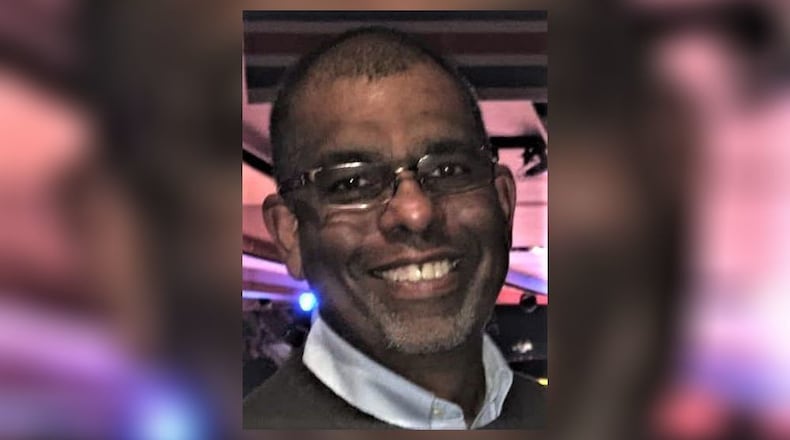

Ray Marcano’s column appears on these pages each Sunday.

About the Author