The Washington Post covered a raucous town hall that the train company inexplicitly skipped. NPR’s “what to know about the derailment” provided an excellent primer on the wreck. CBS, CNN, NBC, and even Al Jazeera have covered the incident.

The train, pulling 150 cars, derailed on Feb. 3. Three dozen cars went off the tracks, and 11 contained hazardous materials — including five with the man-made, cancer-causing substance vinyl chloride. For the roughly 4,800 residents of East Palestine, on the Pennsylvania border some 40 miles west of Pittsburgh, the current short-term angst will soon turn to long-term worry.

But what happens when the story subsides and the big boys go home?

The Lisbon Morning Journal is the closest newspaper to East Palestine, about 13 miles away. The Salem News has covered the story, and they’re 30 miles away. Particle Media’s online site, Newsbreak, aggregates news content, so that’s useful.

But the train derailment highlights a problem that has affected small communities and areas from Tarboro, North Carolina, to Tucson, Arizona.

Some 360 newspapers closed from the start of the pandemic, according to a report published in the New York Times. The problem is so acute that one in five Americans live in a news desert with limited access to local news, the Times reported.

Ohio has fared particularly poorly. Since 2004, the state has lost 32% of its newspapers, according to a study by Policy Matters. Most of those companies were run by small operators who cared about the communities they covered.

In years past, the Youngstown Vindicator would have unleashed its army of journalists to travel the 30 minutes to East Palestine. The Vindicator once had the staff and resources to support its 160,000 Sunday circulation product. But the newspaper collapsed under the weight of circulation declines and financial losses and closed in 2019, with a Sunday circulation of just 32,000.

The East Palestine train derailment lays bare what happens when the community loses its news sources.

Newsgathering goes far beyond the daily reporting of who said what at a press conference or who spoke to a crowd at a community gathering. That’s fairly simply blocking and tackling.

I wonder who will go more in-depth.

Who will tell the stories of the townspeople who will be scared for years by the wreck? Who will monitor whether residents start leaving, which would have a cascading effect on property tax revenue and the city’s school district? Who will chronicle the families and children who stay behind and worry about their health?

Who will monitor health department reports to see if residents start getting sick?

Who will act as a watchdog to monitor state officials, who will be charged with ensuring that Norfolk Southern makes restitution, in whatever form that takes? Who will file public records requests to examine the records of any settlements? If there are lawsuits, who will go to the courthouse and report on the findings?

Without reporters and news sources, the people of East Palestine don’t have an independent news source that keeps officials on their toes.

When people say that local media doesn’t matter, take a look at what’s happening a four-hour drive east of the Dayton area. The big boys will go home because they have so many other issues to tackle. Eventually, the citizens of East Palestine will feel the frustration of living in a news desert.

Somehow, we need to strengthen local news, not continue to watch it wither.

Dying newspapers mean there are fewer independent avenues to help communities, fewer ways to cover tragedy, and fewer ways to hold companies and agencies accountable through reporting.

Local news matters. Let’s do a better job supporting it.

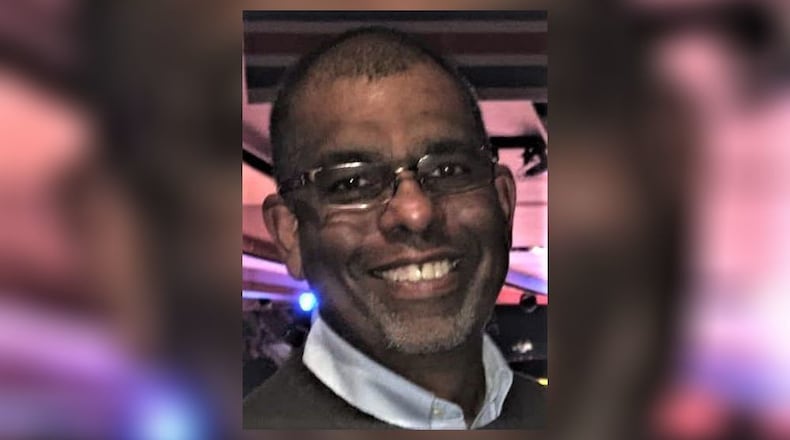

Ray Marcano’s column appears on these pages each Sunday. He can be reached at raymarcanoddn@gmail.com

About the Author