A judge sentenced Brad Stewart of Xenia to life without parole after he shot Jacob Scoby in the face and killed him.

While in prison on other charges, Debord bragged he killed 29-year-old Joshua Shortt, prosecutors said. Mosley took a plea deal to avoid the death penalty and apologized in court. Stewart stole a witness’s truck and was later arrested in it.

Should those men have been subject to the death penalty?

The debate has once again started in Ohio. Lawmakers have proposed two competing bills — one that would ban the death penalty and another that would keep it. Legislators are rehashing old arguments based, in part, on their morality instead of debating whether the death penalty can be fairly applied in cases that deserve it. (Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine has suspended executions in the state).

I get the arguments against it. Since 1973, at least 200 wrongly convicted people who were sentenced to death have been exonerated, including 11 in Ohio, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. Black people disproportionally make up death row inmates (and those in jail). They face an unforgiving system that sentences them to longer prison terms than others convicted of the same crimes.

Additionally, it’s hard, in some instances, to trust police and prosecutors. Look at the case of Joe D’Ambrosio, who served 20 years on Ohio’s death row after he was sentenced in a felony murder case. Despite no physical evidence tying him to the crime, he was convicted on the testimony of a criminal. Later, a judge found a prosecutor withheld important information from the defense. D’Ambrosio was exonerated and released from prison.

Those examples aren’t reasons to dismiss the death penalty. They’re reasons to examine a law enforcement system that can sometimes act as if it’s above the law by ignoring or hiding evidence to the detriment of human beings.

Any death penalty discussion needs to start with how the system can improve to ensure fairness for those on trial.

There should be a discussion on the penalties law enforcement officials face if they engage in prosecutorial misconduct or knowingly withhold evidence, as has happened far too often, including in the D’Ambrosio case. Between 2018 and 2021, Ohio judges found more than 100 cases of improper conduct or mistakes by prosecutors, according to a report heard on NPR.

Then, lawmakers and others can dive deeper. What are the death penalty criteria? The Ohio Revised Code lists the crimes that can result in execution, but it doesn’t get to the testimony and other factors that can lead to death.

A single witness — especially a crook looking to save his own skin with testimony — doesn’t cut it. But does a combination of DNA, video, and eyewitness evidence for capital crimes warrant the death penalty?

There should also be a discussion about the maximum length of time an inmate spends on death row. Someone who meets a death penalty criterion should have the sentence carried out within a specific time. I don’t know what the time is — 10 years? — but it would force the courts and the defense to move faster, which is only fair to the defendant. If there’s no resolution, convert the sentence to life without parole.

Otherwise, these long delays result in cases like that of Sammy Moreland, the notorious murderer who slaughtered a Dayton family in 1985 and has been on death row since 1986.

That’s almost 40 years.

The answer to the death penalty debate isn’t “yes,” or “no,” two simplistic answers to a complex societal issue. We must fix several law enforcement and judicial issues before we can debate whether life in a cage or death for the most heinous among us is the correct form of punishment.

Otherwise, we’re stuck in a morality play with no good answers.

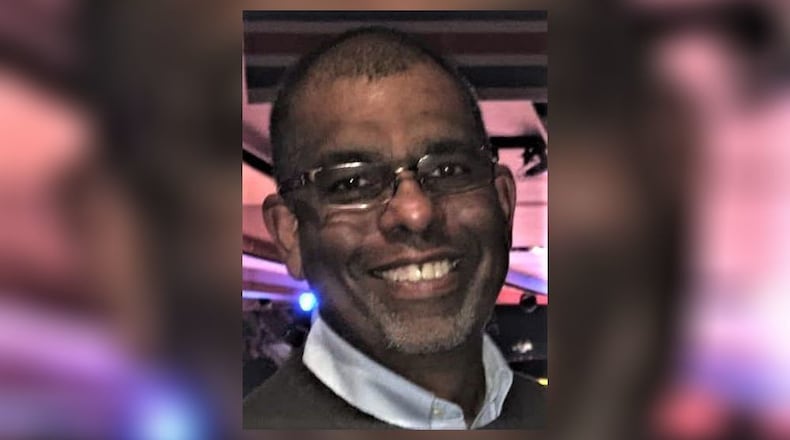

Ray Marcano’s column appears on these pages each Sunday.

About the Author