State statistics were then sent on to the Centers for Disease Control where they were tabulated and aggregated into the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. We depended on this report, and news stories about its contents, to provide context for what we were seeing on the front lines in the ER.

The blotchy skin lesions were determined to be Kaposi’s Sarcoma, a deadly cancer that was seen in patients with suppressed immune systems. As cases soared, the national press began reporting on the strange “gay cancer.” The stigma of homosexuality and fear of a “gay” disease meant that gays in other parts of the country often couldn’t find medical treatment when they fell ill. San Francisco was known as a haven for alternative lifestyles, so patients who couldn’t get care where they lived would be flown to San Francisco and brought directly to the ER from the airport.

I recall one emaciated, barely conscious young man who arrived from SFO clinging to a folder of his medical records, a note pinned to his coat with his name and a plea that we take care of him.

At every change of shift, we discussed the latest info on the disease. Were there any promising new ideas for treatment? To what extent were we at risk? We still didn’t know how the illness was transmitted. It wasn’t standard practice to wear gloves when touching patients patients, but at one point it was suggested that we wear gloves while caring for “those patients” — a costly suggestion since all we had were sterile surgery gloves. Nursing staff discussed it, then agreed to use gloves, but we’d wear them for all patients. We didn’t want to make some patients feel that they were untouchable. We were intensely focused on learning about the disease as it rampaged around us, and progress was frustratingly slow. As we understood more about the pathophysiology and transmission, and drug and treatment trials showed us how to better proceed, the picture of what we were dealing with gradually sharpened.

Our ER crew lost co-workers, family members, friends and neighbors during the AIDS pandemic, but by the time it subsided, we’d gained the knowledge needed to contain the disease going forward.

AIDS spurred dramatic improvements in the systems for tracking and sharing disease data on an international scale. In the decades that followed, there were outbreaks of highly contagious deadly diseases abroad, as well as the looming threat of terrorist attacks. ER staff & first responders trained and drilled, taped into hazmat suits with breathing apparatus strapped to our backs, in case of Ebola or a chemical weapon attack.

We felt prepared for most anything. But of course, we weren’t.

As an ER nurse in Dayton in early 2020, when we first learned that a new, highly contagious and deadly virus was headed for America, the reaction within the medical community was familiar to me. Everyone scrambled to gather and share information about the disease with colleagues in other cities and countries, a process now vastly facilitated by the internet. As we grappled with a glut of inconsistent reports, people in the US began to fall ill and quickly die.

Everyone was justifiably afraid and looked to people in positions of authority for guidance. Leaders at every level adopted theories that made sense to them at the time, and told us what to do.

Having worked through the AIDS pandemic, I knew some of that guidance was bound to be wrong. There were just too many unknowns requiring trial and error and time to work out. In retrospect, we can see where some plausible theories and improvised treatments were off-target, and lives were lost. But we don’t experience pandemics with unknown pathogens in retrospect - we experience them in linear time.

Through continuous education, nurses, physicians and other professional healthcare providers are accustomed to keeping up with the latest right answers, and incorporating them into our routine practice. That can’t happen as fast as we need it to under pandemic conditions. Many of us who cared for patients during COVID are marked by the experience, carrying grief and a collective sense of failure that somehow feels personal. This is also part of the pattern of a pandemic. Recognizing that may help us grant ourselves some grace, and know it was enough to stay in the fray and see it through.

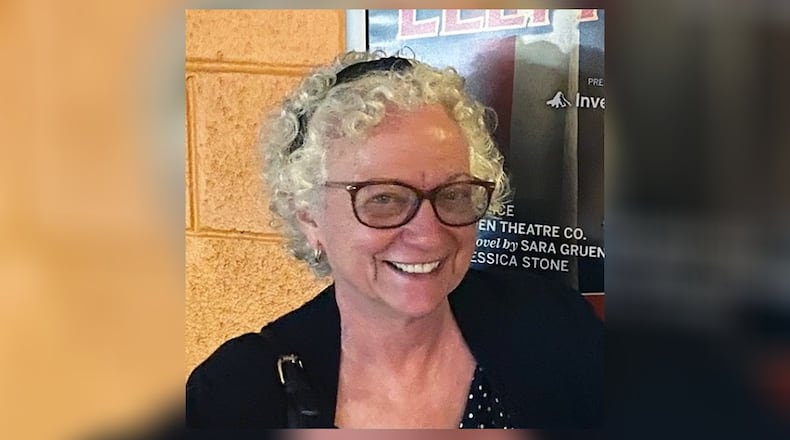

Janet Michaelis has worked in ERs in four states. She is currently the Government Relations Chair for the Ohio Emergency Nurses Association.

About the Author