Back in 2017, a landmark University of North Carolina study identified 1,300 U.S. communities as news deserts. By 2020, that figure had jumped to 1,800. In the last 20+ years, the U.S. has lost more than half the workforce of daily newspaper reporters — from 56,000 in 2001 to fewer than 27,000 today. Some 2,500 daily and weekly papers have stopped publishing since 2005. Today, an average of two papers shut down every week. A generation of promising young reporters have chosen other career paths.

While national polls show that local TV and newspaper journalism remains, by far, the most trusted news source, citizens in many rural and suburban communities are left with nothing but a cacophony of cable talking heads, radio windbags, partisan tweeters, and Facebook fomenters. In these news deserts, communities lack the local news stories that once served as a shared foundation of information – that “first draft of history”–often the starting point from which a community could address its concerns and problems.

With more than 85 percent of adults today owning smartphones, we indeed have easy access to all sorts of national news and entertainment stories, but also fervent misinformation. And in this age of the internet, many of us tend to seek information that affirms our own values and beliefs. According to a 2019 Brookings Institution study, millions of Americans today see only national stories, and many of those “focus heavily on partisan conflict.” More alarming still, Brookings found the decline in local reporting has been accompanied by “a diminished capacity to hold elected officials and other local leaders accountable and a general disengagement from local politics.” (We are all familiar with elected politicians who fabricate their resumes, knowing it is unlikely local reporters will be vetting them.)

A major problem facing local journalism initiatives is that most philanthropic funding for journalism today goes to national initiatives such as ProPublica. One national effort, however, Report for America (RFA) is specifically devoted to recruiting and adding reporters to understaffed newsrooms through salary matches. Some of our best journalism students at Miami started their careers in RFA jobs in Columbus and Cincinnati. RFA support allows newspapers to report on rural areas that many “downsized” papers had stopped covering. Still, the top national news outlets, based chiefly in New York and Washington, D.C., do not see news deserts as a national problem, paying only occasional attention to the crisis.

More than 20 years ago, the Boston Globe spotlighted a regional problem of child sexual abuse by Catholic priests. The regional Globe, at that time owned by the New York Times, was better positioned to circulate its stories nationally to other papers through the Times wire service. Within a short time, as other local papers investigated the crisis in their regional archdioceses, this was no longer just a story about a few local “bad apple” priests here and there, but a systemic global problem in the Catholic Church. But 20 years ago, we had a larger network of journalists who were able to report on the scope and impact of the abuse. Similarly, the story of local news deserts is not about the closing of one paper here and another paper there. It is the story of an entire network, critical to a nation’s welfare, that has lost its moorings. Still, many pundits with the power to reach mass audiences are not connecting the dots, not even recognizing that the loss of local journalism is a major national story.

When we face national crises such as race relations, wealth disparity, or our partisan divide, pundits—especially on cable TV—call for a “national conversation.” In fact, the conversations that foster real change are, almost by definition, local. Yet in places where there are no reporters to interview citizens, vet candidates, and cover town meetings, these stories and those conversations that happen during local cafe lunches or at breakfasts at MacDonald’s are never covered.

Since the internet emerged, newspaper advertising has plummeted. Many newsrooms still operate under a dysfunctional business model in which “middlemen” — Google and Facebook — rake in roughly 70 percent of digital newspaper ad revenue, although they gather no news themselves. Newspapers today still make most of their money from subscribers and print ads. While the digital behemoths support various news projects, including RFA, they could do more to share revenue with local journalism. More states could do what New Jersey did with its Civic Information Bill, putting serious money toward helping local journalism. Universities, especially wealthy ones, also need to do more. Vartan Gregorian, former Brown University president, once called journalism “the quintessential knowledge profession,” and called on universities to better support it. “Our democracy,” he wrote, “depends on journalism to keep its institutions challenged and responsive to the public’s needs, and the quality of the profession demands the best a university can offer.”

Individually, we can all do more to insure we are getting the news that keeps us well informed. We can ask our local community foundation to start newspaper funds, like we have in Oxford. We can form a consortium to start up a local news outlet, supported by businesses and colleges. That partnership between Cox and Miami had a breakthrough this year, with Miami journalism students now contributing weekly to Cox’s Oxford Press.

National initiatives such as RFA are doing much to reverse the disastrous trends in local journalism. But the national news media–-often reluctant to cover journalism itself as a news story—must do a better job. Individually, we can also write our elected representatives and ask what they are doing. Back when our newest Ohio senator, J.D. Vance, was on the college speaking circuit, he visited Miami, where his cousin (who later worked as a DDN reporter) was a journalism student. At the time, Vance seemed interested in building bridges to help heal our partisan divide and in improving that state of local journalism in Ohio. Back then, he said he might be interested in helping. Now Senator Vance has a real chance. Write to him.

In the 1780s – before he was president — Thomas Jefferson wrote a letter to a delegate to the Continental Congress about the importance of a free press as a watchdog on government. He famously said if he had to choose between “a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.” Our Constitution singles out only one business enterprise by name for protection in the Bill of Rights – “the press.” Since colonial America, newspapers have helped us make choices on everything from the food we eat to the representatives we elect. Local journalism has long been at the center of democracy, telling our stories and documenting a community’s life, and now it needs our support.

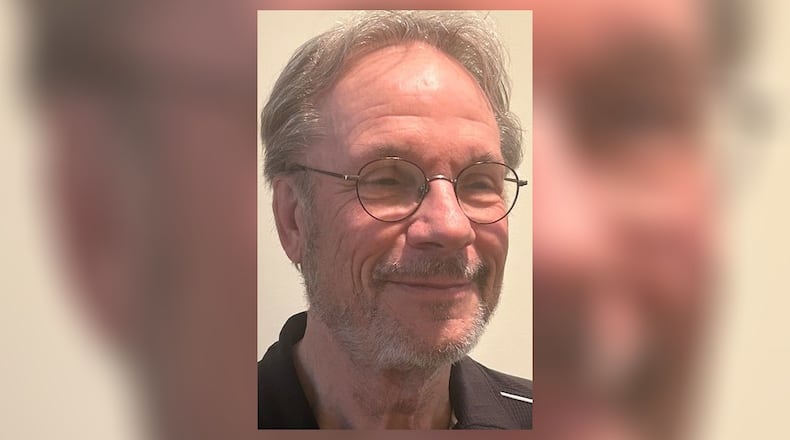

Richard Campbell is professor emeritus and founding chair of the Media, Journalism & Film department at Miami University. Campbell is also proud graduate of Carroll High School, Class of ‘67, where he wrote his first news story.

About the Author