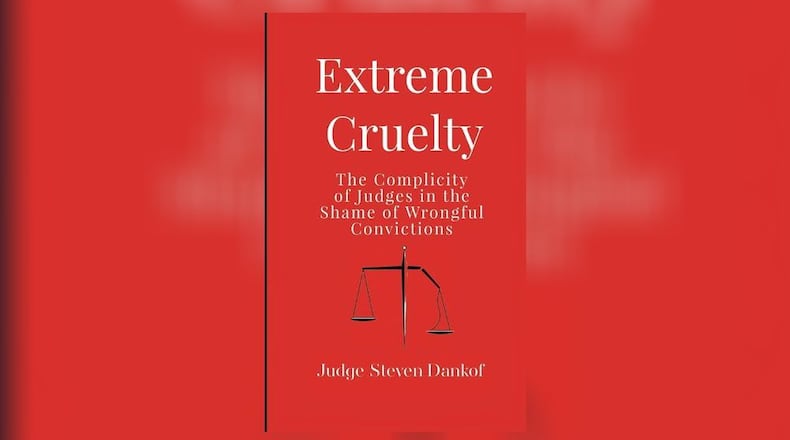

Innocent people have been executed. Innocent people have gotten imprisoned for decades. How does this happen? Of course, every trial is different and when wrongful convictions occur it isn’t exclusively the fault of the judge. In some cases, the person on trial was being represented by a defense attorney who wasn’t doing a competent job.

Dankof cites a trial in which a defense attorney was actually asleep while the client was getting set up for a wrongful conviction. The trial judge was there seeing all this and did nothing to prevent that conviction from happening. When a judge acts like a second shadow prosecutor how is justice truly being served?

The trial judge probably represents the last chance most wrongfully convicted citizens will have. According to Judge Dankof convictions that get appealed rarely are overturned because appeals courts don’t seem to have much appetite for identifying and correcting judicial blunders, mistakes that can cost innocent people years of their lives, or their actual lives.

The author describes how he tries to run his courtroom and the great care he takes to make sure those on trial are considered innocent unless they are proven otherwise because so many aspects of how trials proceed can influence the outcomes. How was the jury prepared for the trial? What was the judge’s demeanor? So many variables.

Judge Dankof is so cautious about how these things are done that he will not even refer to the person on trial as “the defendant” because this person has not been tried or proven guilty. Calling them “defendants” can create bias in the minds of jurors. Dankof addresses them by name: Ms. Smith, Mr. Jones, etc.

Perhaps you scoff at the notion of wrongful convictions? Dankof cites statistics from the National Registration of Exonerations: Since 1989: 3,499 exonerations, those exonerated represent 31,900 years of wrongful imprisonment.

Those figures do not include wrongfully convicted, un-exonerated inmates who remain incarcerated. For those who were exonerated: 64% involved perjury/false accusation, 60% were official misconduct, 27% had been mistakenly identified, 25% had false/misleading forensic evidence, 13% were false confessions, and a staggering 53% of those wrongful convictions were of African-Americans.

What do those wrongful convictions have in common? Trial judges were overseeing those trials. Judge Dankof believes we can do better. We must do better.

Vick Mickunas of Yellow Springs interviews authors every Saturday at 7 a.m. and on Sundays at 10:30 a.m. on WYSO-FM (91.3). For more information, visit www.wyso.org/programs/book-nook. Contact him at vick@vickmickunas.com.

Credit: Contributed

Credit: Contributed

About the Author