That story involves the Dayton cop who not only exposed Rose’s bookie, but also sparked an investigation of police corruption characterized as the greatest scandal in Dayton police history.

That cop, former Dayton Police Detective Sgt. Dennis K. Haller, passed away in 2023, allowing the Dayton Daily News to report on interviews that this news outlet agreed not to use while he was alive.

Like Rose, Haller appeared destined for greatness from the outset of his career. In 1964, Haller became the first officer in his department to be awarded its highest honor, the Medal of Valor, for entering a burning home to rescue six people.

Haller possessed both brains and brawn, earning a master’s degree in corrections from Xavier University as well as praise for skills as a tough football linebacker.

Everything changed instantly in Haller’s life on Sept. 13, 1979, when Scott, his 17-year-old son, committed suicide with Haller’s police handgun.

This is the event that would lead Haller to blow the whistle on law enforcement, authoring an “Anonymous Memo” that he would share with the Dayton Daily News. The memo pulled back the curtain on pervasive corruption in the Dayton police department.

This story is the first time the Dayton Daily News is identifying Haller as the author of the Anonymous Memo.

Officers indicted

As one of his department’s polygraph (lie detector) examiners, Haller screened applicants to the elite Organized Crime Squad and periodically re-examined members of the unit to assure they remained uncorrupted. He became sickened by the admissions some police officers made during those exams.

One applicant for the squad, Haller wrote in the memo, “even revealed the fact that he planted narcotics on suspects and his sergeant ... did the same thing.”

Haller wrote he was also one of five officers selected in 1973 to attend an “electronics school ... so they could tap telephone lines with more expertise” even though local and state police in Ohio then had no legal authority to engage in such activity.

Haller also noted that a detective in the Organized Crime Squad reported the illegal wiretapping around 1973 that managed “to start a very minor investigation” until some members of the squad signed a sworn statement “stating that they had no knowledge of wiretapping” and the whistleblower “went back to being in uniform demoralized has hell.”

Soon after Scott’s death, Haller sent the Dayton Daily News a copy of his memo detailing the police corruption, including his own transgressions.

But the newspaper was unable to find an essential second source to corroborate the information in Haller’s memo until two former Dayton police detectives became targets of an FBI investigation into their allegedly accepting bribes from a drug dealer.

Claiming they were targets because of their knowledge of law enforcement corruption, the officers corroborated many of the claims contained in the Anonymous Memo. The Dayton Daily News’ reporting into the Anonymous Memo’s claims led to the appointment of Troy attorney Jose M. Lopez as special prosecutor to investigate.

Credit: Dayton Daily News

Credit: Dayton Daily News

Lopez said in an August 2023 interview he’s convinced Scott’s death is what motivated Haller to write the Anonymous Memo.

“Everybody, they made no bones about it,” Lopez said of Haller authoring the memo. “He never got over this thing with his son.”

Lopez said Haller was also driven by his belief that “whatever sins I’ve committed in this life; I’m going to try and right this.”

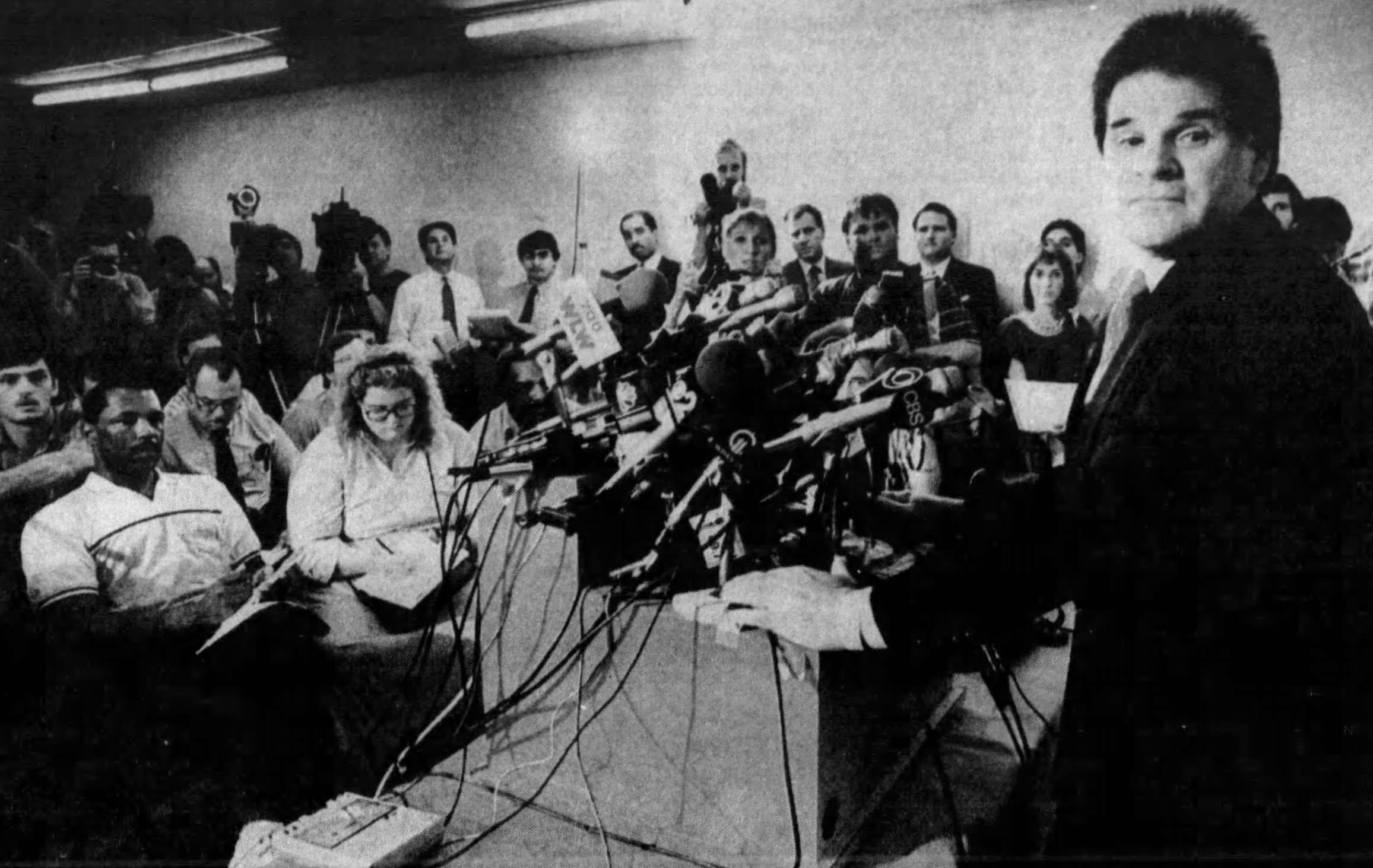

Lopez said Haller’s memo “is what got my investigation off dead center” and eventually helped enable him to convince a grand jury in 1985 to approve criminal charges against nearly 20 current and former law enforcement officers. The charges ranged from tampering with evidence, dereliction of duty, eavesdropping and interfering with civil rights to perjury and involuntary manslaughter.

They include:

- The deputy director of the Dayton Police Department was indicted on charges of perjury, possession of criminal tools, tampering with evidence, interfering with telephone messages, dereliction of duty and interfering with civil rights. He resigned from the department and pleaded no contest to misdemeanor charges of dereliction of duty and interfering with civil rights. He was fined $500 and given a year’s unsupervised release. He was admitted to the prosecutor’s diversion program, at the conclusion of which the remaining felony charges were dismissed.

- The commander of the investigations division pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor charge of failure to report a crime. He was fined $100 and given a suspended jail sentence. He retired from the department two weeks after his guilty plea.

- A sergeant in the organized crime unit pleaded no contest to a misdemeanor charge of unlawful restraint. The charge related to a 1976 drug arrest in which the officer said he planted flour on a man, then claimed it was narcotics and arrested him. He received a $100 fine and a suspended jail sentence. He was not disciplined by the police department.

- An organized crime unit detective was indicted on two counts of perjury and one count of tampering with evidence. The charges related to an allegedly falsified search warrant in a 1982 investigation in Beavercreek. The detective had resigned from the department to run for mayor of Dayton, and was acquitted on the charges by a Greene County jury.

- A Montgomery County sheriff’s deputy pleaded guilty to a felony charge of perjury. The charge was the result of testimony he gave in a 1981 trial where he falsely testified that there was no illegal electronic surveillance used during an investigation. The deputy was admitted to the Montgomery County Prosecutor’s Office diversion program, after which the case was dismissed.

- A sergeant and detective with the Montgomery County Sheriff’s Office pleaded no contest to misdemeanor charges of failure to report a crime. Both were found guilty, fined $50 and given suspended jail terms. One was suspended from the department for three days, and the other for two days.

A ‘cesspool’

Except for a former partner, Haller said he was shunned by his many former police officer friends because of the Anonymous Memo.

He also noted the Fraternal Order of Police no longer sent him a “courtesy sticker” cops paste on the bumpers of their private cars to avoid traffic tickets.

“They don’t do much good anymore, anyway,” Haller chuckled.

But Haller said he was convinced the Anonymous Memo and Lopez investigation achieved his goal of making the Dayton Police Department “a better place for men and women to work.”

“The Dayton Police Department was a (expletive) cesspool prior to that,” he said.

In 1989, Haller was convicted of reporting taxable income in 1984 of $16,000 when it was actually $54,500. He was sentenced to 30 days at a halfway house, fined $2,000, placed on probation for five years and ordered to perform 250 hours of community service.

While not disputing the charge, Haller said he thought the charge was a “final kiss” from federal authorities for his cooperation with Lopez.

“I kinda felt the same way myself,” Lopez said, noting the FBI “was really passive in my investigation.”

The FBI Special Agent in Charge of the Dayton office at the time, Lopez said, “didn’t even want to get his toe in the water.”

Lopez described Haller as “bright, he was sensitive, and he was actually fun to be around and talk to and get his insights.”

“Denny was a very cooperative person.” Lopez said in a recent interview. “He was very helpful. I thought he was a straight up guy. I’ve got nothing but good things to say about Denny Haller.”

Lopez noted that he sought to have Haller’s federal tax conviction expunged. Ohio law permitted such an expungement at the time, but federal authorities would not honor it, he said.

During multiple interviews over several years, Haller never mentioned being awarded the Medal of Valor. But he often spoke with much affection about the courage and dedication of police officers he was proud of have served with, including the one who came to his rescue with his gun blazing when Haller was felled in a shootout.

And while no one can any more take away his status as a hero than they can take away Rose becoming Major League Baseball’s all-time hits leader, Haller never asked for a police hero’s funeral or even a published obituary.

He asked that he be granted just one kind favor — that his ashes be placed next to Scott’s grave.

GEM CITY GAMBLE

A project from the Dayton Daily News

Former Dayton police Detective Dennis Haller’s career spanned a dark time for the Dayton Police Department. Haller was a source for Dayton Daily News reporter Wes Hills, who retired in 2004 after 30 years at the paper, and agreed to share information with Hills on the condition it stay confidential until Haller’s death, which happened in 2023.

Now, we bring you Gem City Gamble, a series that uses Hills’ interviews and notes to shed new light on the largest police corruption scandal in city history and how police wiretapping and a spurned bookie may have contributed to the downfall of baseball legend Pete Rose.

About the Author