» The future of AI: How tech could transform our lives in the Dayton region

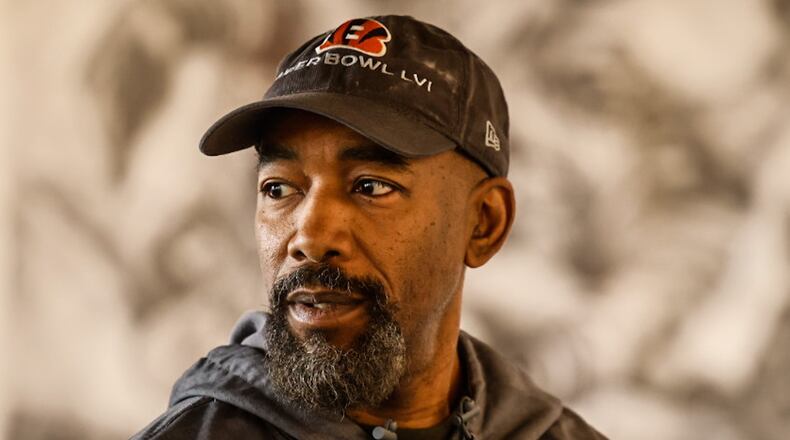

James Pate, artist and owner of Black Palette Gallery at 1139 West Third St. in Dayton, said he got wind of the AI art trend early on.

“My first reaction was I just thought it was extremely interesting,” Pate said. “I embraced it, I thought of it as a tool, something that I could use as reference. And then I just started imagining all the different ways that it might be utilized.”

Pate, who works in multiple physical art media, also teaches art education at schools around the Dayton area and sees artificial intelligence as another tool in a creative person’s repertoire.

“I look at it as part of this evolution of the human capacity,” he said. “Personally, I don’t feel threatened by it. Just like a lot of things that have occurred where we can help society, you get individuals that see how they can use it in more selfish ways.”

Copyright

AI image generators train on millions of images created by thousands of artists and photographers who post their work online. As the model learns from the art contributed to the dataset, users are able to generate images in seconds.

Users can even generate specific images in an artist’s style, so long as that person’s work is used to train the model. However, many artists see this as theft, as the images were “scraped” from websites and used in the model without artists’ consent. As it stands, the artist whose style is referenced will never see a dime for their work being used in AI image generators.

“Artists are the ones that produce the work. It’s cut and dried,” Pate said. “Utilizing someone’s work, someone’s intellectual property, this is a no brainer. You have to compensate them. Be just as creative with thinking about that, as you were with developing the algorithm.”

A group of artists filed a class-action lawsuit against Stability AI, developer of Stable Diffusion, DeviantArt and Midjourney, alleging copyright violations in January. Getty Images followed with a lawsuit against Stable Diffusion in February, claiming the developers had stolen over 12 million of its copyrighted photos.

Credit: JIM NOELKER

Credit: JIM NOELKER

Replacing workers

In a sense, ChatGPT also “scrapes” words and styles from writers and authors across the internet, able to mimic the writing styles of writers of all kinds. Writers are also concerned that AI will take their jobs.

More than 11,000 film and TV writers went on strike last week, for the first time in 15 years, seeking to put strict guardrails around how studios use generative image and text software.

Even if writers aren’t completely replaced by AI, members of the Writer’s Guild of America are concerned that they will be paid even less to rewrite whatever ChatGPT outputs, which writers say would completely undermine the creative process.

“The average person who’s hiring a writer for any reason doesn’t understand what they do most of the time, and just convincing them that they need this work done in the first place is a monumental task,” said Gery Deer, who owns and operates PR firm GLD Communications out of Jamestown.

“We’re already having a struggle getting people to pay for creative work,” he said. “From a customer service standpoint, how can I in good conscience charge someone for something like this? Is it right for me, because I’m paying a subscription for a copywriting program, to charge you for the thing that they created?

While ChatGPT doesn’t have a legal case against it, the program poses significant ethical questions for PR specialists who choose to use it, Deer said. Deer said he will not be using AI in his work, nor will any editors or writers who work with him.

”We were taught to have a conscience in school, that plagiarism and stealing things from other people and letting someone else do your homework for you was wrong,” he said. “I have to face my clients. I have to face the people who read my column every week in the newspaper, and I will be cheating them if I don’t do the work myself,” he said.

Credit: JIM NOELKER

Credit: JIM NOELKER

The artistic soul

Whether or not artificial intelligence outputs have substantive creative value is a topic of debate. Copyright law, as it currently stands, is designed to protect manifestations of the human soul, for which artificial intelligence does not qualify. So far.

However, AI art does have the ability to make that human connection, Pate said.

“AI art is not going to be living art. The way that you will see and experience it would be through a print, or on a screen,” Pate said. “But the average person will look at it, and they might still feel whatever the artist was delivering.”

On the flipside, artists and writers are concerned that taking the human out of the equation leads to tone-deafness, lack of nuance and weakening of what art is supposed to mean to human life in the first place.

“I think at any point any person’s job is potentially lost to automation, to mechanization to computerization. That’s the that’s the flow of progress, and who are we to stand in the way of progress?” Deer said. “But the problem is when you take the humanity out of something like this, the nuance of the message is lost. No matter how good this thing can crank something out, the nuance of the message is not there.”

About the Author