“I ain’t (misleading) ya,” Skinner growled to his female companion, using a vulgar term. “It seems he’s been dodging me and dodging me for three (expletive) years!”

The tape-recording Skinner obtained on that January 1986 night reveals he had a powerful motive to settle the score over Rose’s refusal to pay a $30,000 gambling debt. Skinner faced the loss of essential credibility with gamblers if he allowed anyone to get away with stiffing him, noted former Dayton Police Detective Sgt. Dennis K. Haller.

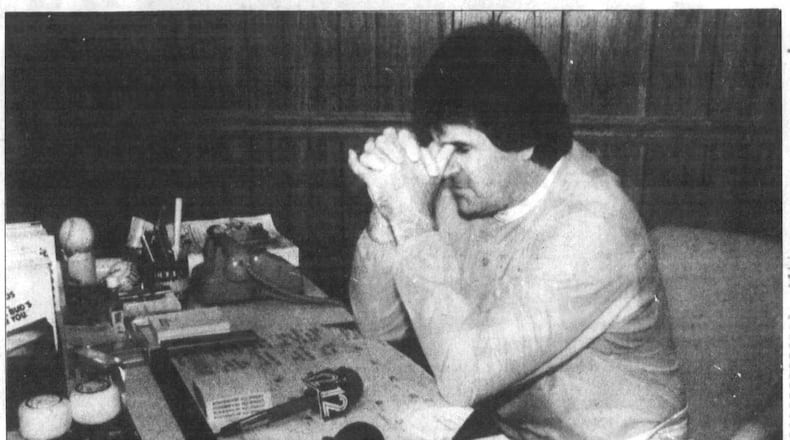

Prior to his death in July 2023, Haller suggested Rose’s downfall traces back to his failure to pay Skinner. Haller believed Skinner was also an FBI informant whom the feds went to great lengths to protect.

Credit: Dayton Daily News

Rose didn’t just refuse to pay the debt to Skinner — he rubbed Skinner’s nose in the way he stiffed him.

When Skinner suggested an installment plan, Rose declined and noted: “I’ve got a guy who owes me 17,000.”

“What do you mean, a bookmaker?” Skinner asked.

“Yeah. Oh, he’s good for it. It’s just for a week.”

Rose was basically telling Skinner that after tapping out his credit limit with him, he had moved on to another bookie rather than paying the $30,000.

“Oh, like I heard you were firing the guy in Hamilton there, some Ron or somebody,” Skinner said to Rose, according to the tape.

This was a reference to Ronald Peters, the man who initially implicated Rose in the gambling investigation and laid off some bets to Skinner. Peters actually lived in Franklin, 17 miles from Hamilton.

Illegal wiretapping

This isn’t the only tape recording made of Skinner’s bookie activities.

An illegal wiretap placed on Skinner’s home in 1973 by two members of the Dayton Police Organized Crime Squad nearly exposed the illegal activity, according to a memo Haller provided to the Dayton Daily News in the early 1980s.

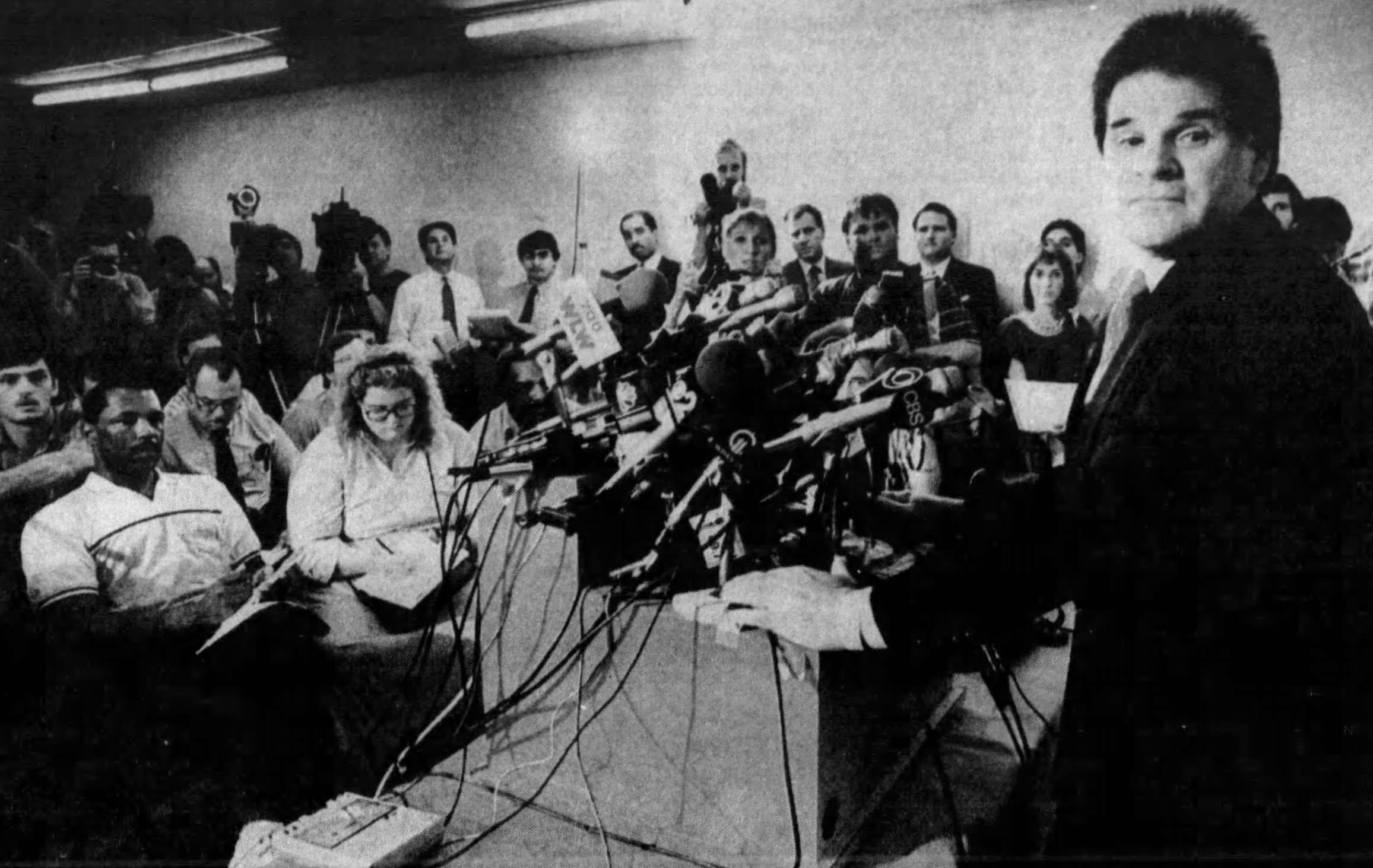

Dayton Daily News reporting on the so-called “Anonymous Memo” led to the appointment of Troy attorney Jose M. Lopez as a special prosecutor to investigate claims of widespread corruption in the Dayton Police Department.

The memo noted “the telephone company” discovered an expensive “parallel line transmitter” on a pole behind Skinner’s home. “The costly transmitter could not be recovered because to go to the phone company would reveal the illegal activity.”

Dayton police didn’t limit the wiretapping to Dayton.

The following year, the Anonymous Memo states Haller tapped the phone of a Miamisburg bookie in Skinner’s organization who was subsequently convicted.

Haller also noted the wiretapping wasn’t limited to bookies. He said his squad conducted illegal wiretapping on “narcotics dealers, political activists, and politicians.”

Seeking evidence to prosecute politicians wasn’t the primary purpose of wiretapping their phones, Haller said. He said information obtained about their lives, like being gay, was used to control them. He cited keeping the Lopez investigation from expanding into a larger federal investigation as one example of exercising that control.

There is evidence the illegal use of electronic surveillance continued until at least 1981.

Lopez said Haller’s squad concealed purchasing wiretapping equipment by obtaining funds from the Organized Crime Unit’s budget “and nobody was checking that.”

Often working closely with the FBI on gambling and other investigations, Haller said that when a close associate of Skinner became the target of a federal investigation, “Skinner became an FBI snitch to save her.” And when Rose stiffed Skinner regarding the $30,000 gambling debt, Haller suspected Skinner went to the FBI for payback.

Skinner’s companion

Skinner’s companion in the meeting with Rose was a woman who would only agree to be identified as “Legs.”

Legs said Skinner had both the motive and opportunity to finger Rose. In addition to being stiffed by Rose, she noted Skinner knew Ron Peters.

“Peters once visited my home with a girlfriend,” she said. “They used my pool.”

Asked if Skinner would have had any motive to become an informant, Legs suggested, like Haller, that Skinner may have wanted “to save” his close associate from being investigated by the FBI. “He (Skinner) would have thrown me to the wolves, but he would have done anything” to save his close associate.

She also noted that Skinner “went to the federal building in Cincinnati a lot. I went with him about three times.” The federal building is where the headquarters for the FBI and other federal agencies are located for the Southern District of Ohio.

Legs said Skinner would go to meet with someone while “I had a seat and waited with a magazine” until he returned. “I didn’t go back” to where Skinner was meeting someone.

She also insisted Skinner wouldn’t have worried about any repercussions from informing, no matter how big the target.

“He wasn’t afraid of anything,” Legs insisted.

Legs had no direct evidence that Skinner became an informant in the Rose investigation. But she recalled one more thing that suggested someone in law enforcement was protecting him.

“He knew he was wired,” she said. “He told me that.”

Skinner’s home raided

Court records confirm the FBI obtained court authorization to wiretap Skinner.

That wiretap obtained information that Skinner’s close associate sometimes ran his bookie operation.

The wiretap was part of what former FBI Special Agent Thomas R. Mygrants described in a sworn statement as “a nationwide investigation being coordinated by the San Francisco Division of the FBI” into a “huge bookmaking/money laundering operation” operated by “Ronald Sacco, an associate of La Cosa Nostra.”

Mygrants’ statement was filed on Aug. 13, 1997 in U.S. District Court in Dayton as part of action seeking forfeiture of Skinner’s former Dayton home.

In 1987, Legs told a Dayton Daily News reporter that Skinner put his secret taping of Rose in a safe in his home. The newspaper did not write a story about her claim at that time, concluding it might lead to the tape being destroyed.

When the FBI raided his home in June 1992, it discovered the tape recordings precisely where Legs said she saw them in 1987 — in Skinner’s safe, according to their search warrant.

The FBI seized “three metal pipes six to eight inches long and two inches in diameter with threaded end caps ... and two revolvers,” but left the tapes behind.

“Consultation between Assistant United States Attorney Gregory G. Lockhart and SA (Special Agent) W. Keith Kirkpatrick resulted in Kirkpatrick’s misunderstanding that the tapes would not be seizable under the stated scope of the warrant,” FBI agent John T. Finnegan noted in the warrant. “The tapes were therefore not seized.”

The FBI never indicated what evidence of a crime it found to seize the metal pipes or whether it examined their contents.

“That’s where he (Skinner) kept his cocaine for personal use.” Legs said.

Finnegan provided evidence indicating Skinner could have been arrested immediately on a charge of being a felon in possession of firearms. He noted in the warrant that Skinner was sentenced in Kentucky to five years in prison in 1982 for “conspiracy.” In 1955, Skinner was also sentenced to 3.5 years in prison in Indiana for “owning and operating an illegal gambling business.”

A week after the first search, on July 6, 1992, Finnegan obtained a second search warrant to search Skinner’s home and seized a full-size audio cassette tape and a micro tape from the safe.

Finnegan said it was “unknown if other tapes disappeared” during the week the safe’s contents were left unsecured.

Haller scoffed at the FBI for failing to seize the tapes immediately.

“What you do is you take the (expletive) things, you seize them,” he said.

Haller said if a court later rules that they shouldn’t have been seized, “you give them back.”

He noted bookies record all bets placed with them in case gamblers claim they didn’t make certain bets. This is why they can be seized because they are “instrumental with a bookie operation.”

After discovering what happened to the evidence seized from Skinner’s home, the Dayton Daily News requested copies of the seized tapes on Aug. 20, 1998. On Oct. 13, 1998, Chief U.S. District Court Judge Walter H. Rice ordered the government to show cause why they should not be released.

A single tape was provided to the newspaper by Lockhart in December 2002.

Criminal enterprise

In addition to gambling, the search warrant indicated Skinner earned substantial income from selling drugs.

Finnegan cited a source in the warrant who said he made purchases of “high quality cocaine from Skinner on numerous occasions” to “supply various bands which play at Hara Arena.” This source said he had also seen “$300,000 to $400,000 in cash in a safe in a back bedroom in Skinner’s home as well as other large amounts of cash hidden elsewhere.”

This source also claimed that he “overheard a conversation in which Skinner claimed that, while in the DR (Dominican Republic), he ... had been able to withdraw proceeds of their lay off gambling activities ... just prior to raids” by law enforcement in which $310 million in gambling proceeds were seized from various banking institutions used by Ronald (The Cigar) Sacco, a Mafia associate.

Investigators said Sacco was running the largest illegal sports betting ring in U.S. history, taking in $100 million a month.

Despite having overwhelming evidence of operating an illegal gambling business and potentially other crimes, the FBI never sought to prosecute Skinner.

Lockhart said he is unaware of why Skinner was never charged.

“If they (FBI) were using someone as an informant ... and I don’t know that’s the case ... we don’t want to charge him ... because there is a bigger case and he’s cooperating,” Lockhart said. “In the Skinner case, I don’t recall them (FBI) ever coming back to us and saying this is what we found, and we want to proceed to indictment.”

In 1994, Sacco pleaded guilty to gambling charges and was sentenced to six years in prison.

Skinner, and the FBI’s case against him, died in 1996.

GEM CITY GAMBLE

A project from the Dayton Daily News

Former Dayton police Detective Dennis Haller’s career spanned a dark time for the Dayton Police Department. Haller was a source for Dayton Daily News reporter Wes Hills, who retired in 2004 after 30 years at the paper, and agreed to share information with Hills on the condition it stay confidential until Haller’s death, which happened in 2023.

Now, we bring you Gem City Gamble, a series that uses Hills’ interviews and notes to shed new light on the largest police corruption scandal in city history and how police wiretapping and a spurned bookie may have contributed to the downfall of baseball legend Pete Rose.

About the Author