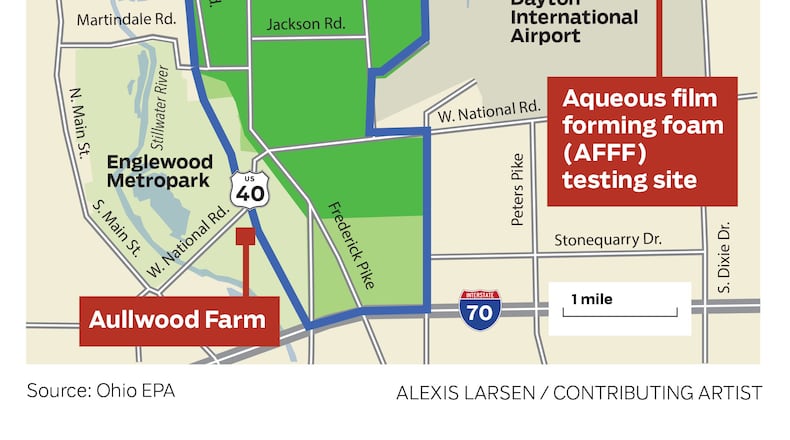

Several miles from the airport testing site, drinking water wells at Aullwood Audubon Farm Discovery Center and surrounding Butler Twp. homes have been found to be contaminated with PFAS, and property owners are seeking answers to how this could have occurred.

Between 2014 and 2020, firefighters spilled or discharged the Federal Aviation Administration-mandated substance called aqueous film forming foam — also referred to as firefighting foam or AFFF — that’s used to extinguish jet fuel and other highly flammable liquid fires on airport grounds, according to city of Dayton documents that the newspaper obtained through a records request. The chemicals tend to seep into groundwater.

Credit:

Credit:

AFFF has about 50% PFAS by volume, meaning that each discharge is “highly, highly concentrated,” said Abinash Agrawal, a Wright State University earth science professor and groundwater expert. In addition, AFFF dissolves in water easily, and can move quickly through the soil to reach the groundwater, he said. So it’s likely that the toxins used at the airport migrated to Butler Twp., and contaminated the wells there, he said.

The Dayton Daily News Path Forward project digs into solutions to the biggest issues facing our community, including the safety and sustainability of our drinking water.

The city of Dayton, which operates the airport, said there’s no correlation between the use of firefighting foam at the airport and the toxins detected in nearby communities. The city, however, has two separate lawsuits pending against PFAS manufacturers and Wright-Patterson Air Force Base and the Department of Defense, in part because it claims the base’s use of firefighting foam contaminated a well field used by the city of Dayton to supply drinking water.

“Unfortunately, PFAS is pervasive in our society, and was used in food products, septic systems and numerous other industrial applications,” the city said in a statement. “It is our understanding that the Ohio EPA has not determined the source of the PFAS contamination at Aullwood, and that an extensive study of the area’s geology and groundwater flow would be necessary to even begin to make this determination, especially with the numerous potential sources in the area.”

The Ohio EPA and the Ohio Department of Health confirmed to the Daily News that they have not determined the source, nor has the state scheduled a study.

After high levels of PFAS were detected at Aullwood last year, The Ohio Department of Health sampled 49 wells in the surrounding community. The aim was to determine the severity of the problem and make recommendations on next steps and health risks to property owners. The purpose of the testing was not intended to determine the source of contamination, the agency said.

How dangerous are PFAS?

PFAS are a group of synthetic chemicals that were developed in the 1940s. They are found in numerous industrial and consumer products such as carpeting, upholstery and food packaging. Manufacturing and processing facilities that use the substances in products, airports and military installations are partially responsible for releasing the chemicals into the air, soil and water, according the the U.S. EPA.

Most people in the United States have been exposed to PFAS because the chemicals have been widely used for more than 80 years, the agency said.

Exposure to PFAS, dubbed forever chemicals because they’re considered chemically nearly indestructible, can lead to increased risk of high blood pressure or pre-eclampsia in pregnant women, increased cholesterol levels and changes in liver enzymes, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The toxins can also cause decreased vaccine response in children, small decreases in infant birth weights and increased risk of kidney or testicular cancer.

Exposure to the toxins in drinking water is higher when compared to exposure in consumer products, the CDC said. Some products that may contain PFAS include:

- Some grease-resistant paper, fast food containers/wrappers, microwave popcorn bags, pizza boxes and candy wrappers

- Nonstick cookware

- Stain resistant coatings used on carpets, upholstery and other fabrics

- Water resistant clothing

- Cleaning products

- Personal care products (shampoo, dental floss) and cosmetics (nail polish, eye makeup)

- Paints, varnishes and sealants

The U.S. EPA does not regulate PFAS, although it’s inching closer to doing so. On Monday the agency announced it plans to set aggressive drinking water limits for PFAS under the Safe Drinking Water Act and will require PFAS manufacturers to report on how toxic their products are, according to media reports. In addition, the government will designate PFAS as hazardous substances under the so-called Superfund law that allows the EPA to force companies responsible for the contamination to pay for the cleanup work or do it themselves.

The agency said it expects a proposed PFAS rule by 2023.

For now, the U.S. EPA’s recommended health advisory level for forever chemicals is 70 parts-per-trillion. A part per trillion is equal to about a grain of sand in an Olympic-size pool. The level is expected to be much lower when the law is enacted.

Ohio adopted the federal PFAS levels. However, a handful of states, including New York and Michigan, have set their levels at 10 and 24 ppt, respectively.

Aullwood’s PFAS level, when the Ohio EPA sampled the center’s well water last year, was 96 parts per trillion. The center is located at 9101 Frederick Pike in Butler Twp., between the city of Englewood on the west and Dayton International Airport to the east.

PFAS discharges on airport grounds

Firefighters disposed of firefighting foam along with a dry, non-toxic chemical agent known as Purple-K that’s also used to fight fires, starting in 2013, according to the documents obtained by the Daily News. Gil Turner, the airport’s director of aviation, said he doesn’t know if firefighting foam was used in previous years because there are no records available. Purple K and AFFF were released into a grassy area on the airport’s northeast corner at a designated training area on airport grounds during annual FAA mandated training and equipment testing, Turner said.

Firefighting foams were either spilled or discharged at the training site five times in 2014, 2015, twice in 2016 and 2020, according to records.

In nearly every discharge recorded, the airport specified that the foam was “sprayed in grass away from drain.” The FAA’s requirement to use AFFF and designate a testing area did not include spraying the foam in the grass; that was the airport’s plan, Turner said. Officials avoided spraying the foam directly into the storm drain because they wanted to ensure that it doesn’t get into nearby groundwater and rivers, he said.

Spraying the foam away from the storm drains or directly in the grass doesn’t do enough to protect groundwater, Agrawal said. Either way, the AFFF would seep into the ground and contaminate the water. While the airport has a permit to use firefighting foam, it is prohibited from releasing the foam and other non-storm water discharges into the drains, according to the Ohio EPA.

Based on the firefighting foam discharges and other evidence, Agrawal, the Wright State groundwater expert, said he believes the airport is the likely source of contamination in the area. He reviewed the city’s documents and also took into consideration the fact that the State of Ohio and some residents detected various levels of the toxins in more than 70 wells throughout the community the past year.

“The groundwater aquifer in the area is fractured bedrock, Agrawal said. “The fractures can allow rapid movement of PFAS-contaminated groundwater to flow downhill to the west, but the contaminated water can also move to the private and public water wells that are actively pumping in the area.”

Agrawal and other scientists from the U.S. EPA and the Ohio State University are conducting their own investigation into the source of the chemicals, he said.

Hydrogeologist Linda Aller, who has tested more than two dozen wells in the area for the chemicals, said the airport is a possible source for the contaminations..But until a study is done to determine the source of PFAS in the area, one can’t be certain, said Aller, who works for Westerville-based Bennett and Williams Environmental Consultants Inc.

Search for non-toxic firefighting foam

The airport stopped discharging the substances into the ground in 2020, after officials learned about the hazards associated with AFFF, Turner said. The city then replaced one of their three trucks, known as Aircraft Rescue and Firefighting — ARFF — with one that allows them to test the AFFF internally. Airport officials used an $833,800 FAA grant to purchase the vehicle.

They also spent $31,800 to retrofit the other two ARFFs with internal AFFF testing equipment.

“While required by federal law to use the current foam to protect life and property, the Dayton Airport continues to lobby the FAA to adopt firefighting foams that do not contain PFAS, and that can effectively put out fires and save lives in the event of an accident,” Turner said.

FAA is working to move away from AFFF-laden PFAS. In a statement to the Daily News, the agency said it continues to partner with the Department of Defense to find a firefighting foam that protects travelers and that does not harm human health or the environment.

To date, the statement continued, the FAA built a testing center to support the necessary research. Despite the impacts of COVID19, officials have performed more than 400 research tests with 15 commercially available and prototype products, and additional research is underway on new foam formulations.

In addition, the bipartisan infrastructure bill includes $10 billion for other agencies to help communities clean up PFAS. Also, the Biden administration this year created a new council that will identify pragmatic approaches that deliver critical protections to the American public.

Recently, the FAA issued an alert to airports, recommending that they use firefighting foam only during emergencies in an effort to limit PFAS.

How widespread is PFAS in local communities?

The Dayton region and the State of Ohio have been grappling with PFAS since 2016, when they were detected in the groundwater at Wright-Patt and Dayton. Then in 2018 Dayton officials sued multiple PFAS manufactures. The city also sued Wright-Patt and the DoD in May, saying contaminated water from the base continues to migrate into the Dayton’s well field, and the Air Force failed to address the problem. Both lawsuits are pending.

In 2020, as part of Gov. Mike DeWine’s efforts to address PFAS, the Ohio EPA tested all 1,500 public drinking water systems across the state for the chemicals. It was during that process that the agency detected PFAS levels at 96 ppt in Aullwood’s drinking water. A short time later, the Ohio Department of Health set out to determine how widespread the problem is in the surrounding community.

The tests determined that five of the wells had PFAS levels below the limit set by the state. Those water systems are located within the boundaries of Old Springfield Road on the north, and Kershner Road on the south. The area, which the ODH said is “most affected,” borders the airport on the east. State health officials issued a citizen’s advisory urging residents in that area to test their wells for PFAS.

Tests of the remaining 44 wells did not detect PFAS, although it’s possible that the contaminants are in the water. Those wells are located in the area that borders Neal-Pearson Road, between Kessler Frederick Road to the north, and Interstate 70, between Meeker and Dog Leg roads to the south. Property owners in that area were advised of the possibility of PFAS in the area. But the ODH is not recommending that they sample their well water, although property owners are free to do so if they choose.

About the Path Forward

Our team of investigative reporters digs into what you identified as pressing issues facing our community. The Path Forward project seeks solutions to these problems by investigating the safety and sustainability of our drinking water. Follow our work at DaytonDailyNews.com/PathForward.

About the Author