One method of gerrymandering is “cracking and packing” minority communities: splitting them between districts to dilute their influence with a larger number of white voters, or drawing districts that are almost exclusively minority-occupied to make sure they’re represented by the smallest possible number of legislators. That accusation has emerged about each of the legislative maps proposed by Republicans, especially in districts around Cincinnati.

Redistricting rules require creating districts that are compact and contiguous, and that comply with state and federal laws, including those protecting minority voting rights; not drawing lines that favor or disfavor a political party, and that don’t “unduly split” counties, townships or cities.

Ohio is required to redraw its state legislative and U.S. House district maps at least every 10 years, in line with results from the most recent U.S. Census.

In 2015 Ohio voters overwhelmingly approved a state constitutional amendment creating a bipartisan commission to draw new state legislative maps, in an effort to reduce partisan gerrymandering. In 2018 voters approved another state constitutional amendment on how to draw new district maps for Ohio’s seats in the U.S. House of Representatives.

This is the first time the Ohio Redistricting Commission and General Assembly have operated under the new laws.

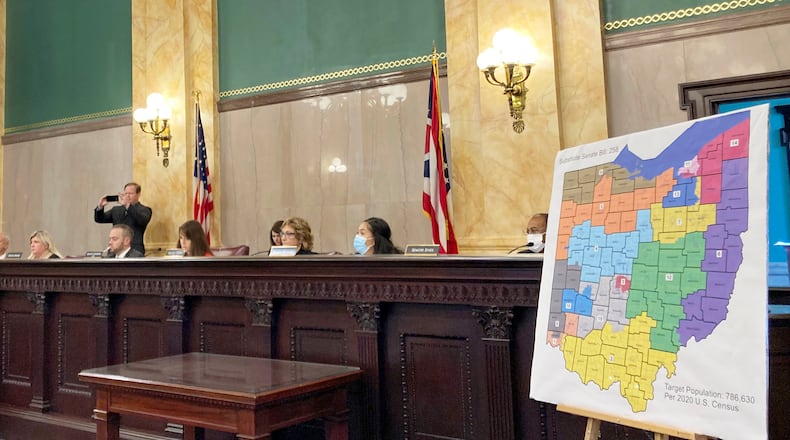

The commission — which is dominated 5-2 by Republicans — repeatedly passed state legislative maps drawn by Republican staff and consultants, without the vote of either Democratic commission member. Republicans have also passed U.S. House district maps without Democratic support.

Voting rights groups sued, and the months-long legal wrangle resulted in a separate primaries in May and August.

The Ohio Supreme Court overturned all of those maps by 4-3 margins, ruling they were gerrymandered to unfairly favor Republicans. Chief Justice Maureen O’Connor, a lifelong Republican, repeatedly joined the court’s three Democrats in ruling against the maps. But she will leave the bench at the end of 2022, and Republicans hope for a friendlier court next year that will endorse the maps they pass.

Although the state supreme court has rejected them, Republican-drawn maps are being used in the 2022 election. Justices have ordered map-drawers to try again, but that too may change with the makeup of the Ohio Supreme Court. Republican legislative leaders have signaled they don’t intend to revisit the district dispute until 2023.

The state legislative maps in use this year will ostensibly create 54 Republican and 45 Democratic House seats, with 18 Republican and 15 Democratic Senate seats, close to the balance sought by the Ohio Supreme Court as reflecting Ohioans’ actual statewide voting preferences. But of those, 19 House and seven Senate seats lean Democratic by less than 4%, while no Republican districts is that close.

The congressional map in use establishes 10 Republican-leaning and five Democratic-leaning seats. But three of the Democratic-leaning seats only do so by less than 5%, while none of the Republican-leaning districts do so by less than 6.64%, according to the breakdown mapmakers distributed. Currently Democrats hold four U.S. House seats to Republicans’ 12.

The state supreme court has urged that maps should match how Ohioans actually vote, which has been about 54% Republican to 46% Democratic in recent elections.

About the Author