“I’m coming here to show respect for the people who gave everything for the next generations to have something to live for; to be free,” Jim Berry, a 20-year Air Force veteran, said Saturday.

According to Pam Berry, all three of her brothers, along with one uncle, served in Vietnam, just as several of her other family members before them served in World War II.

“We were lucky that they all came home,” she said. “It’s just heartbreaking to see all of these (names of) people that didn’t come back and how lucky we are.”

Vietnam veteran Jack Coulson spent seven months in Vietnam at the age of 22 after being drafted into the Army.

Coulson was trained as a repairer of TOW missile systems before receiving his orders to go overseas. He had only been enlisted long enough to finish basic training and schooling. He said he had seen a news segment that foreshadowed his deployment.

“The guy on the news said the United States was sending a TOW missile to Vietnam,” he recalled. “I thought, ‘What? They’re not sending us; they’re probably going to send more experienced people ... I was one of the lucky 10 inexperienced people to go to Vietnam.”

Coulson visited the traveling memorial on Saturday, compelled to find the name of someone he only met briefly, but whom he has never forgotten: Col. William Nolde, who was killed in a rocket attack one day before the Fall of Saigon. Nolde is known as the last American casualty of the Vietnam War.

Coulson found Nolde’s name on the wall quickly. He had a piece of paper and a pencil to create a rubbing of the etched name as a keepsake, a common practice of visitors to the memorial in Washington, D.C.

“I met him,” Coulson said. “He was in a little town about 10 miles from the Cambodian border and I had to go out there to do some work. There were four Americans there and he was one of them ... he was killed 11 hours before the (Paris Peace Accords) went into effect.”

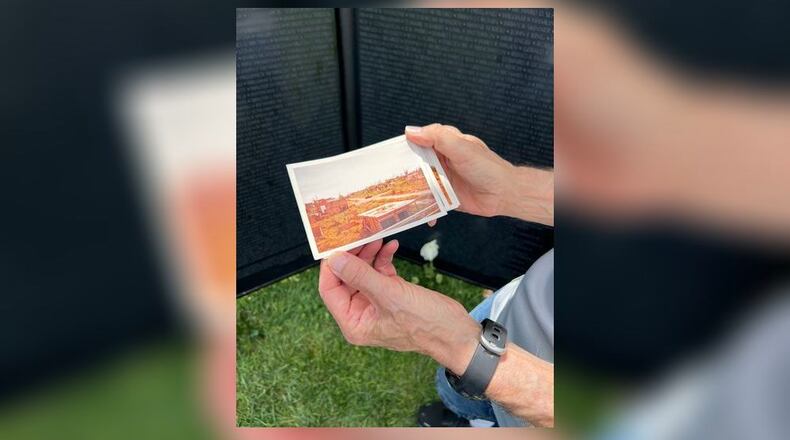

Coulson pulled a folded envelope from his back pocket, opened it, and took out a small stack of old photos. He shuffled through them, describing each scene. “I brought these in case anyone wanted to see,” he said.

Coulson described the scenes depicted in several of the pictures. One shows a bombed Vietnamese town near the Cambodian border. “About six months before I got here, the town just got blown up,” he said.

At a time when he was just entering adulthood, Coulson prepared for deployment to a place he’d never been, for a reason he’d never imagined, to do a job he’d only just learned. Along with him, he took a camera.

Though looking back on such a volatile time in his life, and in American history, can be tough emotionally, like The Wall That Heals, it can also provide a catharsis of sorts.

According to Callie Wright, a staff member with The Wall That Heals and the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, 58,281 names are included in the Vietnam memorial. She said the seemingly simple gesture of reading the names on the wall is profoundly connected to understanding the impact of what was lost during the war.

“You can say the number, but when you say a name, you’re attaching a person to that and understanding that each person on this memorial had someone in their life who loved and cared about them; each individual is someone whose life was cut short,” she said. “When you come out to the wall and you hear stories of these individuals who served and their families, it allows us to pass these stories on and that’s incredibly important.”

About the Author