Here’s a look at some stories from the week of July 28-Aug. 3.

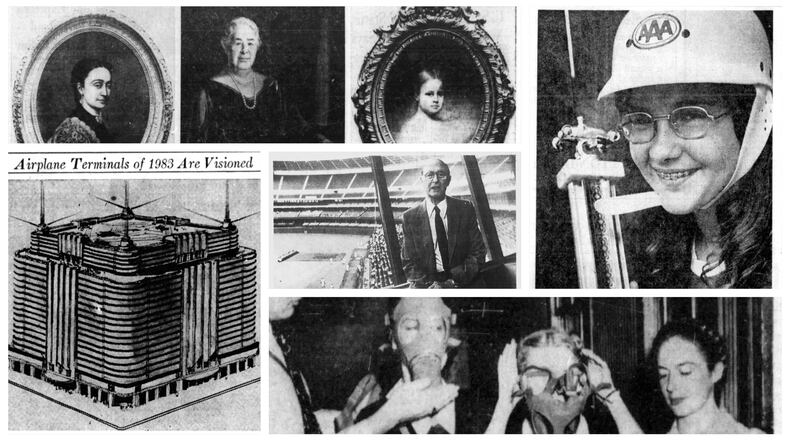

July 30, 1933: Airplane terminals of 1983 are envisioned

In 1933, the airports of 50 years in the future were being dreamed about by Howard Smith, the chairman of the aeronautical committee of the Dayton Chamber of Commerce.

He envisioned that an terminal would be “in the very heart of the city, atop one or more of the tallest buildings. A common roof over four large buildings, or more, of the the tallest buildings.”

The immense structure would house four or more separate airlines.

If this was unavailable, then runways, constructed of steel, could be made to bridge the gaps between individual buildings for a smooth, easily negotiable landing space.

It was assumed that the airplanes of the future would be larger, but also be better able to land safely in much smaller spaces.

Entrance to these rooftop air terminals would be made by direct elevator service from the street level.

The goal was to move airports, which were commonly constructed miles from city business centers, to the middle of cities, eliminating costly travel time and delays.

Aug. 1, 1943: Daytonians being trained to meet possible gas attacks

In the middle of World War II, Daytonians were preparing for the possibility of a tear gas attack.

Tear gas, which had the odor of either fly paper or apple blossoms, burned the eyes, thus the name, “tear gas.”

Allison Kine, chief of the Dayton Council for Defense gas defense corps, knew a lot about war gases and for months was preparing those citizens that wanted to be able to take care of themselves if gas were to ever be used on civilians.

After a lecture, students would get a taste of the real thing. They would enter a gas chamber, filled with tear gas. In there, they would learn to depend on their gas masks and adjust them quickly.

At the time of this story, 75 men and women had reached the “advanced instruction” stage. Those proficient in wearing gas masks could do it in 10 seconds.

About 3,000 gas masks were put in centralized locations at five different points of the city to be used in case of an emergency.

Aug. 2, 1953: Women provide impetus for Dayton art movement

Women who played a vital role in the Dayton arts movement were highlighted in a 1953 edition of the Dayton Daily News.

The most important contribution listed was that of Julia Shaw Carnell, whose generosity made the Dayton Art Institute possible. The Italian structure was said to be “a monument to her vision and faith in the people of Dayton.”

Laura Birge helped in the founding of the Dayton Art association and was a former student of prominent Dayton artist Clara Soule. Soule was widely known for her paintings of children.

Annie Campbell, a contemporary artist, established the first art department at Steele High School. Campbell also served on the board of the art institute and was a vice president of the institution.

Martha Schauer for many years was the director of the Saturday school at the Dayton Art Institute and head of the art department at Stivers high school.

Noteworthy too was the fact that Esther Seaver of the Dayton Art Institute was one of the few women directing a major art museum in the United States.

July 29, 1973: First girl to win Dayton Soap Box Derby

Karla Ledford, 13, became the first girl to win the Dayton Soap Box Derby, in 1973.

Her brother, John, won the local derby in 1969.

Karla, of Huber Heights, was brought up on the derby. Her cousin was racing in them before she was born. She helped work on her brother’s cars for years, back when girls were not allowed to enter the race.

She didn’t get irritated when a local television reporter asked her, “How can a girl build a car?” She just told him how she built the car.

Karla said she liked racing, but that she’ll never go it with “real cars” because it’s too dangerous.

July 31, 1983: Baseball repaying Si Burick’s long love

On this day, Si Burick, long-time sports editor for the Dayton Daily News, was being honored at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown as the 33rd recipient of the J.G. Spink Award for “contributions to baseball writing.”

Burick like to jokingly complain that he had been stuck in the same job for 55 years with no chance for advancement.

He had inherited the job of sports editor when he was just 19 years old. At the time of this story, Burick was 74.

It was said that Burick was known in nearly every press box and sports training camp in the western world. He had attended more World Series, Super Bowls and Olympic Games than most people will watch in a lifetime on television.

He had not missed a Reds Opening Day since 1929. Baseball always remained dear to him.

“I’ve enjoyed my life in this business as much as anyone has enjoyed his business,” said Burick. “I know damn well I’d be dead if I were not working.”

About the Author