Related: How the Oregon District mass shooting unfolded

The highs and lows of this year mirror the ups and downs of life as a police officer today — many feel an outpouring of support locally while also experiencing the difficulties of a job that’s under more scrutiny than ever.

Detective Jorge Del Rio was shot during a federal drug raid on Nov. 4. He died Thursday and his funeral will be held at the University of Dayton Arena on Tuesday. That will be a visible sign of unity, said Springboro Police Chief Jeffrey Kruithoff, who has been in law enforcement for more than 40 years, including as chief in Battle Creek, Michigan.

“They’ll see what the Dayton community feels about its police officers,” he said.

The past five years since the protests in Ferguson, Missouri, have seen growing tension between law enforcement and communities across the nation. And at a time of low unemployment, hiring officers has become harder.

“The negative publicity that law enforcement has received in recent years causes people to not have an interest in the profession,” said Patrick Oliver, head of the criminal justice department at Cedarville University. He worked in law enforcement for 27 years, 16 of them as a police chief in various cities, including Fairborn and Cleveland.

“There’s more criticism of and resentment toward the police in the last five years,” he said.

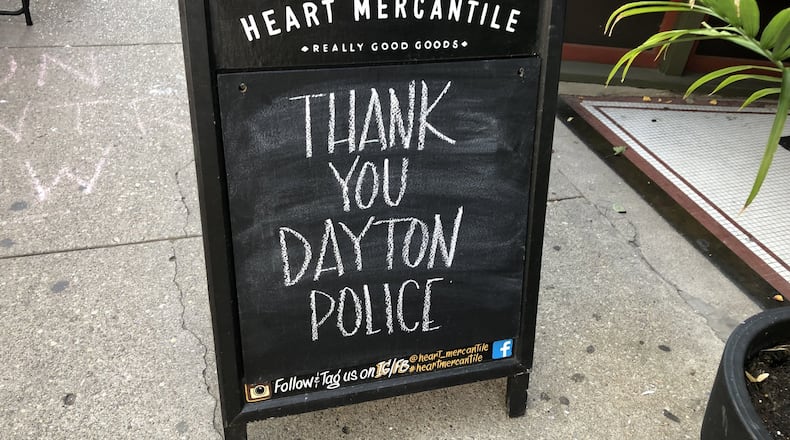

Yet Kruithoff and others said many in Miami Valley communities are supportive of the police, where people stopped to hug officers after the Oregon District shooting.

“I feel it,” Kruithoff said.

Related: KKK rally in Dayton ends without violence, arrests

‘A different time’

When Del Rio joined the Dayton Police Department in 1989, then-sergeant Bob Chabali was his first supervisor. A few years later they worked together again on the narcotics unit.

“It’s a somber time. It’s a tragic time,” Chabali said about the loss of his friend and colleague.

Chabali, a 41-year veteran, retired from the Dayton Police Department in 2015 as assistant chief and is now the police chief in Fairfield Twp. His officers there feel the loss of Del Rio, even though they never met him.

“Everybody here thinks about him,” Chabali said.

Some aspects of policing haven’t changed since those early days when he and Del Rio first worked together.

“Guns, drugs and money have always been tied in together in narcotics,” Chabali said.

Related: Chief Biehl announces death of Det. Del Rio

Police work has always had its risks. A call to a minor traffic accident can result in a dangerous situation, Chabali said. On any given day an officer just doesn’t know if that’s the day an incident gets out of hand, he said, and that hasn’t changed since his days as a street cop.

“It’s the unknown of what call you’re taking, the unknown of who you are dealing with each day,” Chabali said.

But the closure of state psychiatric hospitals has created increased challenges for police officers locally who now spend a lot more of their time dealing with the mentally ill, both Chabali and Oliver said. That at times leaves them feeling more like social workers than police officers.

“Today’s police agencies are taking on roles in our society on a wider range of social issues than ever before,” Oliver said.

A positive changes has been more mental health support for officers, especially in the wake of shootings and other tragedies, Chabali said. Cultures have changed to where it’s encouraged to seek help to deal with the stresses of the job.

“There are many more mental health resources available and a lot more care and follow up (after an incident),” he said.

Those resources will help Dayton officers get through the challenging year they’ve had dealing with a mass shooting and the loss of Del Rio.

“It’s cumulative,” Chabali said. “It adds up.”

Dayton’s officers are to be commended for how they’ve persevered this year, he said.

“Our community has already endured too much senseless tragedy this year,” Mayor Nan Whaley said. “And the Dayton Police Department has risen to the task each and every time. Violence striking the department directly is especially painful.”

Related: Dayton officer shot: FOP starts GoFundMe for Del Rio family

Oliver has had to hand that flag to a crying spouse.

“It’s very difficult … and you tell her how sorry you are that you’ve lost one of your own,” Oliver said.

More scrutiny

The national discourse on police use of force, race relations and community policing has had a huge impact on the job since the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri.

“It’s a different time,” Chabali said. “Obviously we’re under a lot more scrutiny.”

“The majority of Americans support their local police,” Oliver said. But he believes the media presents a negative image of policing that has diminished interest in the job. “The negative voices are the loudest.”

Derrick Foward, president of the Dayton Unit of the NAACP, is the son of a police officer. Dayton police leaders have taken steps to improve the relationship with black communities, he said.

“I believe the citizens in Dayton understand how law enforcement and the community can come together in challenging times,” he said. “But we need to continue to work on coming together before tragic events arise, which is what the police department has been attempting to do through the Dayton Community Police Council.”

He believes holding officers who mistreat people accountable, including more indictments when they clearly broke the law, will increase trust in black communities.

People’s attitudes toward police tend to be based on their experiences and stereotypes, local attorney Anthony VanNoy said. But in general, Dayton officers do a great job of protecting the community to the best of their ability, he said.

The tension between police and communities across the country has existed for more than a half century, at least, Kruithoff said.

Related: Police shooting: ‘We are more resilient’

In the 1960s and 1970s, an “us vs. them” mentality emerged after demonstrations around the country. In the 1990s, departments started to change their tactics, he said, and adopted new procedures such as community policing, problem-oriented policing and, now, predictive policing.

“Has that gone well, universally across the country? No,” Kruithoff said. “I think still you have a lot of police departments that have been slow to embrace the fact that you are merely an extension of the community. We see some examples of that because of things around video, it is clearly an agency that’s not sensitive to the demographics of the community they serve.”

The level of vitriol toward some police officers today can be attributed to several things, he said. Some of it was caused by the Obama administration, when the president and then-Attorney Eric Holder inserted themselves in local incidents such as the arrest of Harvard Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. at his home and the Ferguson shooting.

The media is also complicit, Kruithoff said, because it tends to “press a narrative that perhaps wasn’t fair or completely accurate.”

Police departments also played a role early on, he said. When incidents occurred, some departments would deny it or push back rather than acknowledge it.

Recruitment challenges

The tension between police and the communities they serve has also made recruiting difficult, Kruithoff said.

Recruiting in general has been on the decline nationwide the past two decades, according to a 2018 U.S. Department of Justice report. Between 1997 and 2016, the number of full-time sworn officers per 1,000 residents decreased by 11 percent, according to the report.

As of last month, the Dayton Police Department was behind on its annual recruitment goals for a new academy class. The department started accepting applications for the police academy on Oct. 21. The deadline to apply is Dec. 16.

Related: Will Dayton mass shooting, tornadoes inspire more police recruits?

Within the first two days, the police department received 81 applications, which is significantly fewer than during past recruiting periods.

Within the first 48 hours in past rounds, the city received 119 applications in 2018, 172 in 2017, and 297 in 2016, according to department data.

Unemployment also is lower than during past recruiting efforts.

In 2018, the department received a total of 669 applications — down 42% from 2016 and below the goal of 1,000.

A robust economy, viral videos of some officers across the country being overly aggressive — and at times killing citizens — are some factors that have contributed to the recruiting decline in recent years, officials say. Some recruits complete the training and decide police work is not for them, Kruithoff said, because unlike the way it’s sometimes portrayed in the media, the profession is 80% boredom and 20% excitement.

Minority recruitment is a challenge for just about every police department across the country, Kruithoff said, and they compete with each other for candidates. Police departments should be reflective of the communities they serve, he said, but it’s been especially difficult to recruit women and minorities from various ethnic groups.

Some minority members don’t want to join the force or have other career options, he said.

“I am white, I have made a lifelong journey of trying to understand how it is to live as a different ethnic group,” Kruithoff said. “I have absolutely no clue how difficult it is in the community in which that person was born and raised to join the police. I know it’s difficult when he or she can go out and say, ‘I’ve got a college degree, I can go out and get a job in logistics making twice as much as I will as a police officer.’

“It’s tough,” he said. “And now if I’m from a neighborhood or a community that has had historical tension with the police or problems with the police, I’m not going to rush to that job. So I think it’s going to continue for a while.”

Staff Writer Cornelius Frolik contributed to this report.