Coming Friday

As the world marks the 70th anniversary of D-Day on June 6, local World War II veterans recount their experiences in their own words. A local veteran also shares why he will re-enact his harrowing jump into Normandy on Friday with other WWII veterans.

They are the bravest of the brave.

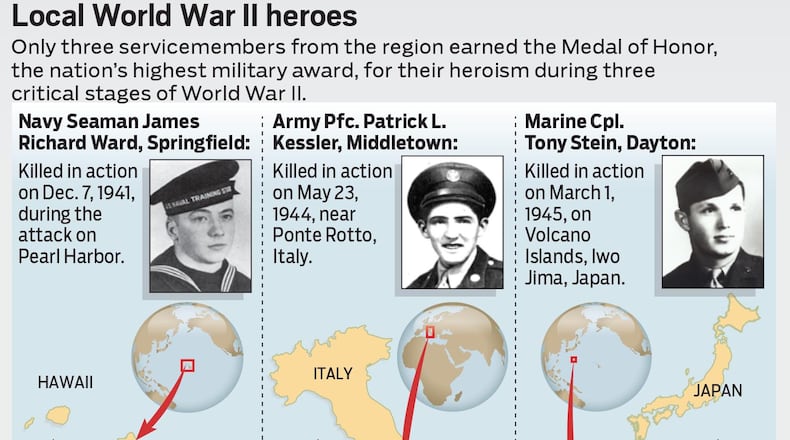

Three men from the area gave their all at the dawn, middle and near the end of the Second World War, earning the nation’s highest military honor and securing a place in history.

The trio — from Dayton, Middletown and Springfield — help tell the story of the area’s contribution in helping end the world’s most destructive conflict.

The time seems suitable to revisit the heroism of what some have called the “Greatest Generation.” Friday is the 70th anniversary of the D-Day invasion and for many this may be a final milestone anniversary for veterans who took part. Some 555 WWII veterans die daily, according to the National World War II Museum in New Orleans.

Bravery is expected and seen among many who serve in uniform. But the Medal of Honor — first conceived and presented in the Civil War — is set aside for those who display valor of an “uncommonly high and of a qualitatively different magnitude,” as the Congressional Research Service put it.

It is the nation’s highest military honor for courage, having been awarded 3,488 times, according to the Congressional Medal of Honor Society. Nineteen people have received the honor twice. The society counts 78 living recipients. A total of 330 Ohioans have received the medal since the Civil War, according to the state’s Department of Veterans Services.

The Medal of Honor was awarded to 32 Ohio servicemen who served in World War II, which remains the United State’s deadliest war. More than 12 million servicemembers fought overseas between 1941 and 1946, with more than 291,000 killed.

“When you get through the many millions who have served, it has been darn few” who have received the Medal of Honor, said David Burrelli, a congressional researcher and a specialist in military manpower policy, who since the mid-1980s has studied the medal’s history.

The medal is often awarded for heroic actions performed during sometimes desperate defensive moves, trying to save fellow soldiers, with clear disregard for one’s own safety, Burrelli said. In many cases, the service-member receiving the honor loses his or her life. (Dr. Mary Walker of Oswego, N.Y., was the only woman awarded the honor, at Bull Run in July 1861.)

The award cannot be “won,” Burrelli emphasized. The person receiving the medal did not take part in a game or a competition.

“In more cases than not, they went in when no one asked them to,” Burrelli said. “I am usually in awe when I read these (Medal of Honor) citations. How could you mentally do it?”

“If they had turned and run, no one would have blamed them,” he added.

Here are the stories of three area servicemen who exemplified the qualities the Medal of Honor recognizes.

James Richard Ward: Baseball slugger and Navy sailor

Seaman James Richard Ward played sandlot ball in Springfield and was a top slugger in the Pacific Fleet in the Navy.

The youth, once described in a newspaper story as “just average” during his formative years in Springfield, would gain another title for doing the extraordinary: Congressional Medal of Honor winner.

And he would give his life so others would live.

Ward would have a destroyer escort, the USS J. Richard Ward 243, an athletic field in Honolulu, a Navy base in Idaho, and an American Legion post in his hometown named the seaman first class who would become the first Clark County resident to die in World War II.

James F. Walsh, 88, then in junior high school, vividly remembers the day in 1940 when the older Ward joined the Navy with his friend, Miles O’Hara, in Springfield.

“They were both jumping up and down having just joined the Navy,” Walsh said in an interview this week. “Little did they know they were going to end up at Pearl Harbor.”

Ward was active in his youth.

Dick, as he was known to his friends, did odd jobs for neighbors, such as washing porches or cutting grass, and had a morning newspaper route to earn money. He liked to fish with his father, Howard, and friends. At Springfield High School, he played football and the trumpet in the band. His prowess in sports extended to basketball, where he played on a local church team.

Baseball was the “prime interest and major joy of his life,” an old newspaper account said. In the sandlot leagues around Springfield, he played shortstop and had a lifetime batting average “well over .300,” according to the article.

Chuck Benston, of Springfield, played baseball with Ward in an American Legion team in 1938.

“He was just like the rest of us,” Benston, 92, recalled in an interview this week. “We played ball. He was a good ball player and a nice guy.”

In the off-season, when Ward wasn’t playing on the ball diamond, he scrimmage in football and played basketball with a church team.

“Never in his life did he outgrow a pair of shoes,” his mother once told a reporter. “Always wore them out.”

When Ward graduated from high school at age 17, he took a job in a factory, but then landed a minor league baseball contract with the Colonels in Shelby, N.C. He earned $80 a month.

His foray into the minor leagues was short. He was replaced by a veteran shortstop about a month later.

Ward got a job as a stoker at a steel mill, but then traded his life as a laborer for Navy sailor.

He found his love of baseball when he graduated from boot camp at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station near Chicago, and was sent aboard the USS Oklahoma, battleship berthed at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, in January 1941.

The ship’s crew won the Pacific Fleet championship in baseball, and Ward had found a sweet spot with the bat. He had a battling average of .538.

“Not to brag, but they think I’m pretty good,” he once told his family. “That helps when you want to get an apple or something in between meals. If I want a haircut, I don’t have to stand in line — I just go right to the front.”

But on Dec. 7, 1941, Ward would be the last in line, by choice.

The Imperial Japanese Navy sprung a surprise attack on Navy ships docked at Pearl Harbor.

The fleet from across the Pacific Ocean launched 350 warplanes — torpedo bombers, dive bombers, and fighters — against U.S. ships at rest on a Sunday morning at Pearl Harbor and Army Air Corps planes based at Hickham Field on the island of Oahu.

The USS Oklahoma was docked at Ford Island in a row of ships, next to the USS Maryland.

Ward was in a turret. The bombing had cut off electricity, and he and other sailors were in darkness.

The 20-year-old seaman first class from Springfield had the only flashlight. He shined it onto a hatchway to allow sailors to escape before the ship capsized.

Ward’s parents learned of their son’s award for the Medal of Honor in a letter from President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

“When it was seen the U.S.S. Oklahoma was going to capsize and the order was given to abandon ship, Ward remained in a turret holding a flashlight so the remainder of the turret crew could see to escape, thereby sacrificing his own life,” the president’s letter read.

The attack killed nearly 2,500 Americans, mostly military personnel. The U.S. military lost 21 ships either sunk or damaged and 328 planes. The Japanese lost 29 planes, five two-man submarines and 70 planes damaged along with 64 dead.

Ward’s parents first learned of his death Feb. 20, 1941, more than two and half months after the attack.

Thinking back across the decades, Benston said this week he was “not surprised” Ward received the Medal of Honor “because thinking about the guy, I thought he had it all together for as young as he was. He was the real thing.”

Patrick L. Kessler: A Fleming Road farewell

Gladys Karacia, 80, of Huber Heights, is the sole surviving sibling of Middletown native and Medal of Honor recipient Pvt. Patrick L. Kessler. She was only 10 when her brother died at 22 near Ponte Rotto, Italy, on May 25, 1944; just two weeks before D-Day when more than 154,000 Allied troops landed on French beaches.

“I really didn’t get to know him too well,” Karacia said.

One memory stands out, however. Kessler returned home to Middletown in December 1943 for a Christmas visit — his final visit home, as it turned out.

“Everybody was happy to see him, because he had been stationed up in Maine,” Karacia recalled.

When he returned to the Army after the visit, he walked to a train station from the family’s Fleming Road home.

“He turned around three times to look at the house before he left, because he knew he wasn’t coming back,” she remembered. “Oh yeah. We were on the porch.”

Kessler later wrote to the family. When he joined the Army, his hair was black. But after a time in the service, he said his hair turned white “overnight,” Karacia said.

“I guess (it was) stress,” she said.

She thinks her mother received a telegram when her brother was killed, but she recalled no memories of receiving the news of his death.

She did recall how the family came together on the news that Kessler had received the Medal of Honor in January 1945. “We were happy that he got the medal. We were all happy over that.”

Does Karacia believe her brother was a hero?

“Oh yes, I do.”

Kessler’s medal citation makes his heroism clear. As part of the force securing the Anzio beachhead in Central Italy, Kessler snaked his way to within 50 yards of an enemy machine gun nest in action near Ponte Rotto. Once he was discovered, “he plunged headlong into the furious chain of automatic fire,” his citation said. “Reaching a spot within six feet of the emplacement he stood over it and killed both the gunner and his assistant, jumped into the gun position, overpowered and captured a third German after a short struggle.”

Kessler then crawled 75 yards through a minefield while two machine guns “concentrated their fire directly on him and shells exploded within ten yards, bowling him over.”

The private first class crawled to within 50 yards of the enemy and “engaged the machine guns in a duel,” the citation said.

“When an artillery shell burst within a few feet of him, he left the cover of a ditch and advanced upon the (German) position in a slow walk,” firing from the hip.

In the teeth of heavy machine gun fire, Kessler reached the edge of the enemy position, killed the gunners and captured 13 Germans, the citation says.

“Then, despite continuous shelling, he started to the rear,” the document said. “After going 25 yards, Private First Class Kessler was fired upon by two snipers only 100 yards away. Several of his prisoners took advantage of this opportunity and attempted to escape; however, … Kessler hit the ground, fired on either flank of his prisoners, forcing them to cover, and then engaged the two snipers in a fire fight, and captured them.”

The removal of that last threat allowed Kessler’s company to advance, capturing its objective without further opposition. Although not seriously injured, he was killed in later action.

“I just couldn’t believe it,” Karacia said of her brother’s heroism.

In a 1988 interview with the Middletown Journal, Karacia remembered that her brother was known for sticking up for underdogs.

And he had an “Irish temper,” she said in an interview this week. In 1988, she recalled an Army chaplain who told her family that “Patrick got so mad (because of) all the guys getting killed. We think this got up his ‘fighting Irish.’”

In 1967, the state renamed its armory the Patrick L. Kessler Ohio Army National Guard Armory in Middletown. It was the first time the Ohio Guard Armory named a facility after an Army serviceman, previous ones were named for National Guardsmen.

While the story of Kessler’s actions isn’t necessarily aired every weekend, it is known, said Sgt. 1st Class Joshua Mann, a Guard historian. Older soldiers make sure new privates know of it, he said.

“I absolutely think that story is told and is passed down,” Mann said.

David Shortt, a U.S. Army veteran and curator of Germantown’s Veterans Memorial Museum, said he has gathered signatures for a petition to Middletown city government to rename a street or a park in that city for Kessler. He hasn’t approached the city yet, but he has almost 500 veterans’ signatures so far, he said last week.

“The World War II veterans talk about Patrick all the time and about how he has been forgotten,” Shortt said.

In 2007, Ft. Stewart, Ga., renamed its elementary school after Kessler, who was a member of the Army base’s 3rd Infantry Division.

Shortt called Kessler’s actions “incredible” and said he was a “typical solider from that generation.”

“What can I say?” Shortt said. “You feel humbled.”

He said he may give Middletown city leaders the petition in the next month.

Tony Stein: Sparring the bigger guy

Vernon “Moon” Miller, a Huber Heights resident, supported the landing of Allied forces on D-Day and saw his share of the war. He also knew Cpl. Tony Stein, a Dayton native who received the Medal of Honor for bravery on the volcanic sands of Iwo Jima, more than half a world from Normandy.

Miller, 88, remembered Stein from the time he was 11 or 12 growing up in old North Dayton. Stein was some six years older than Miller. Their families lived near each other on Troy Street.

Miller called Stein a “loner,” but not one who shunned people. In fact, if you were outnumbered in a fight, Stein was the kind of guy who would stand up for you, he said.

“If one guy fought (you), it was all right,” Miller recalled. “If two or three guys jumped you, he’d be right there with you fighting with you. He didn’t believe in having two or three guys fighting against you.”

Across the decades, Miller has gathered documents on Stein, many of them also collected by the American Legion Tony Stein Post 619, which was chartered in 1946.

Tucked among the papers — including an Our Lady of the Rosary parish certificate of baptism, a marriage license to Joan Strominger and much else besides — is a written recollection from Russ Eschenberg, a boyhood friend of Stein’s who wrote that Stein brought his “fearless and aggressive nature” to the boxing ring to become a 128-pound Golden Gloves champion.

“I would often see Tony sparring with some bigger guy, and aggressively defending himself very well,” Eschenberg recalled.

Stein worked as a tool and die maker as a civilian at General Motor’s Delco Products division, until the U.S. government declassified his job from “exempt” status, allowing Stein to join the military. He enlisted in the Marine Corps Reserve, serving with the 5th Marine Division. Three days before deploying to Iwo Jima, Stein married Joan Strominger on July 21, 1942, in San Diego, before she returned to Dayton to live with her parents on West Siebenthaler Avenue.

Stein’s courage in the boxing ring served him well on the battlefield. Among Miller’s stash of documents on Stein: an April 27, 1945, Western Union telegram from Gen. Alexander A. Vandergrift, the Marine commandant in World War II, to Stein’s mother, Teresa Parks, notifying that her son was killed March 1, 1945, on Iwo Jima.

Despite injuries, Stein volunteered to help clear a ridge of Japanese snipers that day, so that his unit could take an airstrip.

But Eschenberg wrote that it was Stein’s earlier actions, on Feb. 19, that posthumously earned him the Medal of Honor. With his rifle (which he dubbed “Stinger”), Stein attacked and destroyed eight Japanese pillboxes. In the course of his attack, he often ran back and forth to retrieve ammunition, “each time carrying a wounded Marine back with him to receive medical attention,” according to Stein’s citation on the Wright Dunbar Inc. Dayton Walk of Fame.

Dayton resident George Stephens, vice president of the Kiser High School Alumni Association and editor of the association’s newsletter, called Stein’s heroism “incredible.” (Stein attended Kiser for two years before working at a machine shop and joining the Marines.)

“Each time he would run back, he would drag a wounded soldier with him,” Stephens said. “He did that eight times.”

It was while attacking a ninth pillbox that “Stinger” was shot out of Stein’s hands, and he was “seriously wounded,” Eschenberg wrote.

Eleven days later, a sniper’s bullet killed Stein.

“As his company was advancing against some of the most stubbornly defended positions encountered on Iwo Jima, he was hit by enemy machine gun fire,” Lt. Col. J.B. Butterfield wrote to Parks on May 1, 1945. “Tony passed away instantly and suffered no pain whatsoever.

“Before you son was hit, he was carrying out his duties in a most courageous manner,” Butterfield added. “His disregard for his own personal safety was a great inspiration to the men around him. You may be assured you son gave his life as a true Marine, gloriously, fearlessly and proudly.”

“I was not surprised to read about his heroism,” Eschenberg wrote. “I had remembered Tony as a fearless little guy who was destined to do just what he did.”

Stein’s memory was enshrined through not only the medal, but a Navy destroyer escort, the USS Stein, nicknamed the Indomitable. It was commissioned in 1972, later redesignated as a frigate and decommissioned 20 years later. Stein was the the first Marine of 22 to receive the Medal of Honor for heroism on Iwo Jima.

Stein’s heroism was later documented in a 1967 ABC-TV film, “Our Time in Hell” narrated by actor Lee Marvin, who served as a Marine in Would War II.

Today, a bronze statue of Stein stands at the Kiser Alumni Center, 4900 Webster St., Dayton, within the FC Industries Inc. plant. FC Industries was founded by Kiser graduate Frank Casella, who gave space not only to the alumni association, but to Stein’s statue.

The statue stands without boots because, as Stephens explained, Stein found the black sands of Iwo Jima difficult to negotiate with his boots on. He took them off to move more easily, Stephens said.

“He’s one of our real heroes,” Stephens said. “They are dying quickly.”

About the Author