Anyone contracting a respiratory illness shouldn’t assume it’s novel coronavirus; it is far more likely to be a more common malady.

“For example, right now in the U.S., influenza, with 35 million cases last season, is far more commonplace than novel coronavirus,” said U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps Dr. (Lt. Cmdr.) David Shih, a preventive medicine physician and epidemiologist with the Clinical Support Division, Defense Health Agency. He added that those experiencing symptoms of respiratory illness – like coughing, sneezing, shortness of breath and fever – should avoid contact with others and making them sick, Shih said.

“Don’t think you’re being super dedicated by showing up to work when ill,” Shih said. “Likewise, if you’re a duty supervisor, please don’t compel your workers to show up when they’re sick. In the short run, you might get a bit of a productivity boost. In the long run, that person could transmit a respiratory illness to co-workers, and pretty soon you lose way more productivity because your entire office is sick.”

Shih understands that service members stationed in areas of strategic importance and elevated states of readiness are not necessarily in the position to call in sick. In such instances, sick personnel still can take steps to practice effective cough hygiene and use whatever hygienic services they can find to avert hindering readiness by making their fellow service members sick. Frequent thorough hand-washing, for instance, is a cornerstone of respiratory disease prevention.

“You may not have plumbing for washing hands, but hand sanitizer can become your best friend and keep you healthy,” Shih said.

Regarding novel coronavirus, Shih recommends following the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention travel notices. First, avoid all non-essential travel to Wuhan, China, the outbreak’s epicenter. Second, patients who traveled to China in the past 14 days and show symptoms including fever, cough or difficulty breathing, should seek medical care right away, calling the doctor’s office or emergency room in advance to report travel and symptoms, and otherwise avoid contact with others and travel while sick.

The CDC also has guidance for health care professionals, who should evaluate patients with fever and respiratory illness by taking a careful travel history to identify patients under investigation who include those with fever, lower respiratory illness symptoms, and travel history to Wuhan, China, within 14 days prior to symptom onset.

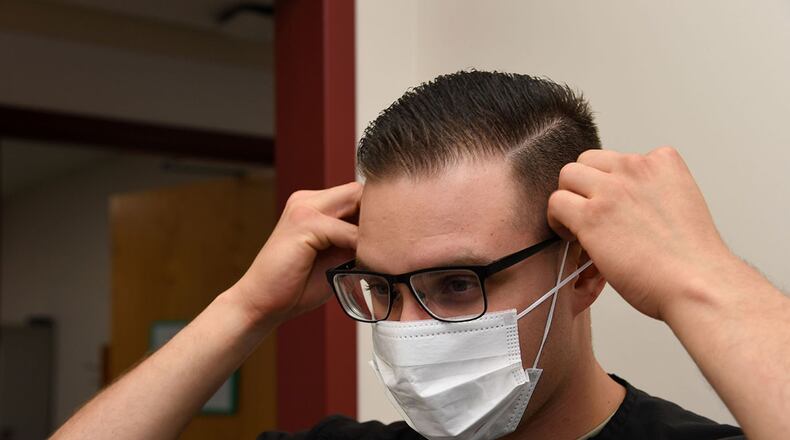

PUIs should wear a surgical mask as soon as they are identified and be evaluated in a private room with the door closed, ideally an airborne infection isolation room if available. Workers caring for PUIs should wear gloves, gowns, masks, eye protection and respiratory protection. Perhaps most importantly, care providers who believe they may be treating a novel coronavirus patient should immediately notify infection control and public health authorities (the installation preventive medicine or public health department at military treatment facilities).

Because novel coronavirus is new, as its name suggests, there is as yet no immunization nor specific treatment. Care providers are instead treating the symptoms – acetaminophen to reduce fever, lozenges and other treatments to soothe sore throats, and, for severe cases, ventilators to help patients breathe.

“Lacking specific treatment,” Shih said, “we must be extra vigilant about basic prevention measures: frequent hand-washing, effective cough and sneeze hygiene, avoiding sick individuals and self-isolating when sick.”

About the Author