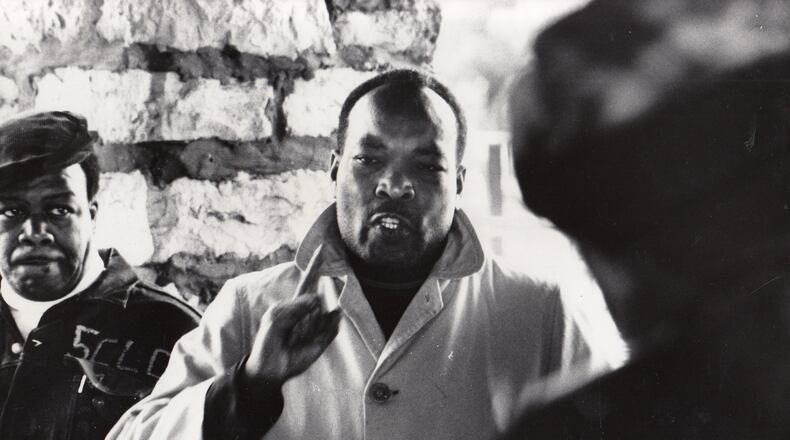

W. Sumpter McIntosh challenged segregation before the issue of racial equality gained national attention. A firm believer in non-violence, McIntosh, known as “Mac,” attempted negotiation to earn equal rights. When his efforts were hampered, he stirred Dayton’s black community to boycott and picket.

As president and founder of the West Side Citizens Council, McIntosh led one of the first civil rights demonstrations in Dayton to protest discriminatory hiring practices at white-owned stores and banks in West Dayton.

Marching along West Third Street in a pouring rain Feb. 25, 1961, he and more than 60 others carried signs that read “Is Freedom Right or Is Freedom White?” and “Why Buy Where You Can’t Work?”

Disappointed with the leadership of the local chapter of the NAACP, McIntosh was instrumental in the opening of a Dayton branch of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), a civil rights organization founded in 1942.

“It’s time for local Negro leaders to wake up to the problems here in Dayton,” he was quoted as saying in a July 21, 1961 Dayton Daily News story. “Not all the problems are in the South.”

Raised in Kansas City, McIntosh was a veteran of the U.S. Navy and a Dayton resident and businessman for 33 years. He was involved in numerous civil rights organizations including serving as the local director of CORE, acting as an advisor to the Dayton chapter of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and as an organizer of marches in Washington D.C. and Selma, Alabama.

McIntosh may have been best known for organizing protests at the Rike-Kumler department store due to alleged hiring discrimination.

Credit: Dayton Daily News archive

Credit: Dayton Daily News archive

After weeks of picketing on downtown Dayton sidewalks, 13 protesters — three of them children — carried placards inside the store and were then arrested according to a July 28, 1963 Dayton Daily News story.

The women and children protesting were escorted out of the store to a paddy wagon but the rest of the group, six men including McIntosh, made their way to the 10th floor office of company president David L. Rike.

Attempting to speak to Rike after the company had refused months of negotiation attempts with CORE, the men lay on the floor when told he was unavailable. They were carried out of the store and into the Safety Building by police officers when they refused to walk.

“At last the white and Negro citizens of this community should realize that we’ve got a race problem here,” he told a reporter while in jail. “It’s been with us for years but nobody was willing to talk about it.”

His continued efforts, along with others, encouraged integration and pushed toward equal rights within Dayton.

Tragically, at age 53, he was shot and killed March 4, 1974 as he tried to stop two men who had robbed Potasky Jewelers in downtown Dayton. The men also killed Dayton Police Sgt. William Mortimer after the crime.

More than 600 people attended a public viewing at the University of Dayton fieldhouse to honor Dayton’s civil rights leader. Then Ohio State Representative C.J. McLin told the crowd, “He carried a torch. When Mac died, the torch never touched the ground. It is out there for all of us to grab.”

About the Author