Not that there weren’t some tense moments in March when Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine and the state health department began imposing restrictions on citizens, businesses and schools in hopes of slowing the spread of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus.

“There was a time where we weren’t really sure what category we fell in when colleges started to close but K-12 schools were still in session every day,” said Alexis Pelisano, a Wittenberg senior who is student-teaching at Northwestern this spring. “When Gov. DeWine said we were going to extend spring break, there was the question of what does this look like for us? How are we how do we fit into this? I think we all felt that way, but Northwestern did a really good job of making sure that all of their teachers were supported, which in turn made sure that my teacher was supporting me, and I was able to support her.”

She also praised the support she received from Wittenberg, where Brian Yontz is an associate professor and chair of the education department.

“It’s been a wild ride,” said Yontz, a 15-year veteran of the department. “This all hit in early March so all our kids were looking forward to their spring breaks, and they were all placed out in in different school districts with different spring breaks. The first couple weeks was just a flurry of trying to answer ‘what if?’ questions.”

Figuring out what to do next required collaborating with the governor’s office, the Ohio Department of Education and the Ohio Department of Higher Education.

DeWine and his team would decide when – or if – schools would reopen this spring while the ODE had to determine what – or if – adjustments would be made to requirements to obtain a teacher’s license this year. The ODHE defines requirements the colleges must maintain to grant a degree in education, so colleges had to look to them for guidance on what standards they could relax if necessary.

David Leitch, interim dean of the school of education at Cedarville University, said navigating the change in policies and regulations was not easy, but there was a pleasant surprise along the way.

“I am not a big fan of sometimes how the state works and the slow motion that they’re in, but in this case they actually did work relatively fast,” Leitch said.

He estimated that within a week, the usual requirement for 12 weeks of student-teaching (along with 100 hours in the classroom called “field experiences”) was cut in half. Whatever amount of the remaining six weeks were lost could be made up through alternative activities.

Because sites for licensing tests had to be closed along with school buildings, a one-year provisional license has been granted to would-be teachers who had not had a chance to take a test. They will be able to teach this fall before having to become certified next year.

As for the alternative options for meeting the student-teaching time requirement, that varied by school and in some cases grade level, Leitch said.

While some continued via online learning, others turned to take-home work that had been previously prepared by the full-time teacher, presenting a challenge for the student-teachers in need of experience developing and executing a lesson plan on their own.

“In that case, we developed assignments to cover the remaining essentially four weeks to get us up to the minimum,” he said. “So that might be watching a video series and writing out a lesson plan based on it.”

That lesson plan would then be presented to other Cedarville students who acted like school pupils while an administrator observed via video conference.

“For example, I just watched them give their math lesson, and I basically graded that math lesson so that would be one part of different assignments that they would do to make up any difference that they might have had,” Leitch said.

Pelisano was among three Wittenberg students who reported being able to carry on with their student-teaching via online video conferencing and other tools.

An intervention specialist, she said working with students in kindergarten through second grade through an online forum was at times challenging, but she felt it was a good experience overall.

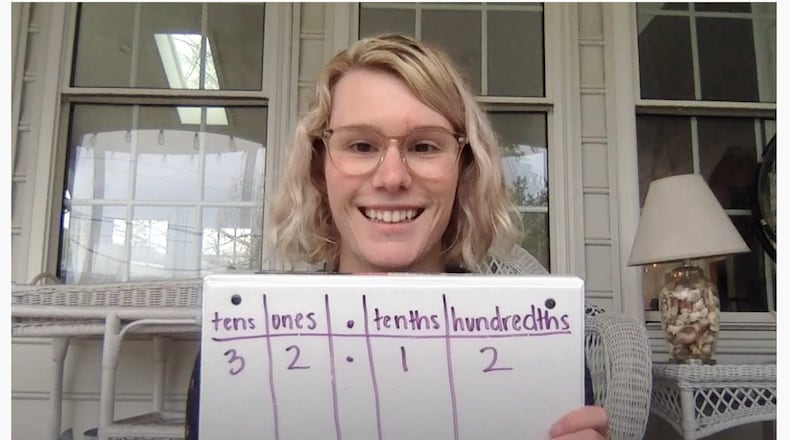

“When things like this happen, you have to jump in and be willing to try anything so that your students are still receiving an education,” said Pelisano, who is from Groveport, Ohio. “I have become more comfortable with different aspects of online teaching such as using Google Meet to conduct lessons and teaching in smaller increments. There is also the awkward skill of videotaping yourself teaching to post for your students to watch.”

Grace Worley, another Wittenberg student from Hudson, Ohio, is aiming to be an art teacher. She is working with middle schoolers at Tecumseh.

“I have been working with my clinical educator to come up with lesson plans and grading the artwork the students turn in to us,” she said. “I work hard to make sure I send the students feedback on their artwork in the same way we would in the classroom to provide a little sense of normalcy. Our students appreciate hearing from us often and seeing that we acknowledge the hard work they are putting into the assignments we send out.”

She came away with high marks from her full-time teacher at Tecumseh, Greg Baker.

“Miss Worley is a very talented artist and for such a young teacher, a very talented teacher,” he said. “The kids began to trust her, ask her questions and look to her as the teacher. All was going as planned and even ahead of schedule when the coronavirus hit.”

Despite having to take everything online, he reported she was still able to become the lead teacher of the class as planned.

“This is just the way it would be if we were still in the classroom,” he said. “We communicate, plan, discuss and share each day. Our process is still the same, but our classroom walls have changed. This experience is proving to be successful. Change, stress, and creativity all continue but together we are giving our seventh grade art students experiences in art that they should remember.”

Of course, working through an internet connection is not the same as getting true, face-to-face interaction.

“In my opinion, it’s always best to be there face-to-face,” Baker said. “There is something about being in the classroom, the immediate interaction with your classmates and the teacher. That’s just very important.”

Elissa Manchester, a Wittenberg student from Columbus, saw first-hand the difference.

Because she is pursuing dual licenses – in early childhood education and as an intervention specialist – she split her time at Graham Elementary School in multiple rooms.

“I learned a lot throughout my eight weeks in a kindergarten class,” she said. “I learned the importance of data collection, classroom management, and most notably, I reaffirmed the importance of a student-to-teacher relationship.

“I am heartbroken that I have not had the same opportunity to build such strong relationships with my first-, second-, and fourth-grade intervention students, but my clinical educator and I have a great relationship where she has trusted me to make video lessons, co-teach zoom lessons, and create assignments for our students – all of which I upload for parents to have direct access to share with their children.”

Yontz suggested all of Wittenberg’s student-teachers this spring learned a valuable lesson while dealing with a situation they hope to never see again.

“Two of the key skills of being a teacher are flexibility and problem solving, and this group of 45 student-teachers were given the ultimate test of being flexible and problem solving and they’ve done a phenomenal job,” he said.

About the Author