First-responders are far more likely to develop PTSD than the general population, and sometimes symptoms do not surface for weeks or months after an incident, experts say. Diagnosis sometimes doesn’t happen until around the six-month mark.

The city and police department are hosting mental health classes and taking other steps to help officers recognize whether they or their peers have psychological scars that may be interfering with their lives and happiness.

“We have a duty to provide care for the officers,” Dayton police Chief Richard Biehl said. “Even if the officer thinks they are doing fine, we have a responsibility for their well-being … and if there is ongoing therapy or treatment needed, that they get it.”

MORE: Living with trauma: Ohio first responders want PTSD coverage

Numerous survivors of the Aug. 4 mass shooting in the entertainment district have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and say they remain haunted by the terrible things they saw and experienced that night.

Some have complained about having trouble sleeping, or of intense nightmares. Some say they are always irritable or angry, or struggle with poor concentration and memory problems.

Survivors have complained about depression, anxiety in crowded spaces and losing interest in things that they always enjoyed.

Police officers are not immune to trauma, and often are exposed to a variety of traumatic events — fatal crashes, suicides, deaths and other violence — over the course of their careers. Studies indicate that between 6% to 30% of first-responders will have PTSD at some point during their careers, said Randon Welton, director of residency training with the department of psychiatry with Wright State University. That compares to about 6% to 7% of the general population, according to some estimates.

“It’s an endemic problem that you find in all the folks who work those jobs,” Welton said.

And most officers never have to respond to a scene like the Oregon District after the shooting, which looked and felt like a war zone. Blood stained the streets. Bullet casings and bodies littered the ground. Gunshot victims cried out for help.

Six officers engaged and killed the gunman on East Fifth Street. Many other officers and first-responders helped apply tourniquets for gunshot victims, took the injured to the hospital and interviewed and counseled witnesses and survivors.

MORE: Oregon District shooting: ‘Every day is a struggle,’ survivor says 6 months later

PTSD symptoms can take time to develop. “Some studies have said that up to a quarter of people who develop post-traumatic stress disorder are diagnosed after six months,” Welton said.

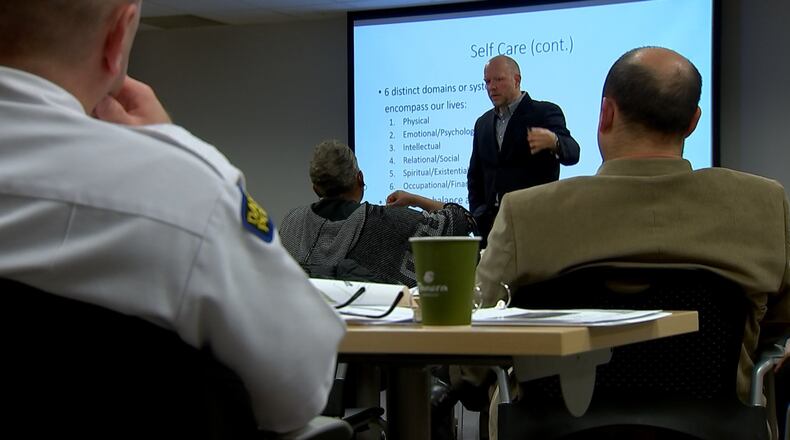

Dayton police officers are required to attend mental health care classes led by Welton and others where they are learning how to identify the signs and symptoms of PTSD and other mental health problems.

Mental health issues still have a stigma among first-responders and professionals whose jobs are to help others, such as law enforcement officers, firefighters, soldiers and EMS crews, Welton said.

“It was seen for a very long time as a sign of weakness,” Welton said. “Our hope is that as more people start telling their stories, as more people are opening up about the problems that post-traumatic stress has caused them, it will be less stigmatized.”

PTSD is a form of injury, and there should be no shame in struggling with it — just as there is no shame in having a broken arm or leg, he said.

MORE: Dayton cops get help to cope with a tragic year

The classic example of PTSD is the combat veteran who is startled easily and may be frightened by loud noises, Welton said, but the disorder can manifest in all sorts of ways that can harm people’s relationships and personal and work lives.

People with PTSD often withdraw socially and become isolated, he said, and they stop interacting in the same ways with friends, family, spouses and partners and their children.

People with PTSD often have trouble performing normal tasks, and they can become very depressed and increase alcohol and drug use, he said. They also have increased risk of suicide.

Bad memories cannot be erased, but PTSD is treatable and people can help get back to normal levels of functioning with talk therapy or medication-assisted treatment, Welton said.

Police officers, their coworkers and supervisors need to “keep an eye on each other” and look for signs of trouble, such as less engagement and out-of-character behaviors, Welton said. Left untreated, PTSD symptoms can get worse, and they can deeply harm people’s quality of life and health, experts say.

MORE: 6 months after Oregon District shooting: ‘We are healing together’

Police work is like “swimming in the sea of human suffering,” Chief Biehl said. He said he worries that officers are struggling with the cumulative trauma of repeated exposure to stressful, dangerous and emotionally draining experiences.

Last year had a series of traumatic incidents, including the hate group rally, the tornadoes, a gruesome crash that killed two children downtown and the fatal shooting of a Dayton police detective.

“Most police officers never experience one of these events in their entire career, much less multiple events like this in a series of months,” Biehl said. “This was a painful year for our community.”

The mental health classes seek to teach officers to take stock of their feelings, mood and actions, as well as share ways to manage adversity and deal with the “residue” of traumatic experiences, Biehl said.

Biehl said he wants officers to learn how to identify emotional and physical needs that require attention. He said officers need to learn to incorporate challenging and traumatic experiences into their lives.

Biehl said there a variety of ways to manage stress and improve mental health. He said got into yoga after struggling with depression for two years. He said he underwent psychological counseling, which had some benefits. But for him, yoga was the real difference-maker because he learned how to regulate his body, breathing, emotions and mind.

Even possessing a good skill set for handing stress and trauma does not mean it’s always easy.

Biehl said he cried almost every day for more than a week after the Oregon District shooting, often when he woke up or at night when he reflected on what he had heard and seen.

Since the mass shooting, some police officers and firefighters have met with Katherine Platoni, a clinical psychologist and expert in war trauma and PTSD who is a survivor of a mass shooting.

Some officers and first-responders had a strong need to talk about their feelings and experiences and try to process what they saw and did, she said.

“Most of them found some solace and some relief in being able to talk about their individual experiences in a very in-depth level,” she said. “Most, if not all of them, are coping exceptionally well, because they had the foresight to deal with this at the onset.”

Some officers needed multiple sessions, while others were able to heal pretty quickly, she said.

Some officers, however, met with Platoni because they were concerned about their fellow officers, who were deeply affected by the shooting and its aftermath, she said.

.

About the Author