Since his early beginnings as a college student and throughout his distinguished career, Goodenough’s research has positively impacted the progress of Air Force science and technology, especially in basic research.

Goodenough’s first introduction to the Air Force was during World War II. In 1943, while studying mathematics at Yale University, Goodenough was called to duty and served as a meteorologist in the Army Air Force.

According to a 2014 interview he had with Bea Perks for Chemistry World, “On one occasion he cleared a flight from an Air Force base in Stephenson, Newfoundland, for General Eisenhower (then Allies supreme commander in the lead up to D-Day), which landed him safely in Paris within six minutes of his ETA.”

Goodenough went on to receive an undergraduate degree in mathematics from Yale and later a Ph.D. in Physics from the University of Chicago in 1952.

The next part of Goodenough’s career was spent at Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Lincoln Laboratory, where he specialized in solid state chemistry and concentrated on the basic and fundamental research leading to the development of random-access memory.

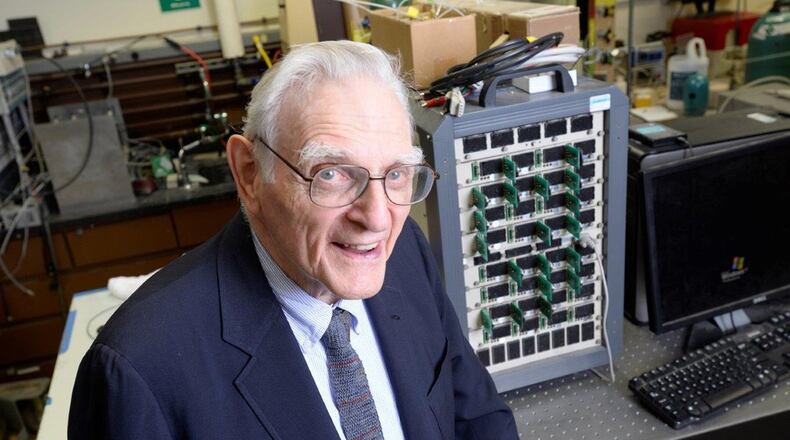

In 1976 Goodenough took a position at the University of Oxford as a professor and headed up the Inorganic Chemistry Laboratory. He was there until 1986 when he moved to the University of Texas at Austin, where he continues his research today. It was during his time at the University Oxford that Goodenough made the lithium-ion battery discovery.

During his time at the University of Oxford, Goodenough had received a basic research grant from AFOSR to study “New Materials for Electrochemical Cells” between 1978 and 1981. The purpose of the research was to design, prepare and categorize new materials for electrochemical cells with a special emphasis placed on solid-solution cathodes for secondary batteries of high specific energy and power.

Denton W. Elliot was the AFOSR program officer who oversaw the grant. In a 1982 summary of the 27th AFOSR Chemical & Atmospheric Sciences Program Review, of which Goodenough’s work was a part, he wrote, “Professor Goodenough and his group have come up with an invention that relates to an electrical device which includes a conductor of hydrogen cations.”

He went on, “This invention is covered under U.S. Patent Application 12058.”

Elliot’s report continued, “Another invention which originated from the Oxford group’s research is concerned with a method of preparing a high surface area form of LiCoO2. This is covered under U.S. Patent Application 135222. It relates to ion conductors. Such ion conductors have potential application as solid-solution in electrochemical cells.”

The high surface area lithium compounds were key in demonstrating how a rechargeable lithium ion battery could be fabricated.

In 1980, Goodenough published a paper in the “Materials Research Bulletin” (Vol. 15, pp 783-789), on his original work in developing lithium cobalt oxide cathodes that led to modern lithium-ion batteries. He acknowledges both AFOSR and the European Energy Commission for supporting his work.

This is a wonderful example of how the AFOSR basic research mission works. In this particular instance, it shows that research funded by AFOSR has directly contributed to enabling modern cell phones, portable computers, electric cars, and modern mobile military technologies.

AFOSR is proud to have Goodenough join an illustrious cadre of scientists who contributed much of their careers exploring the fundamental science that lead to their amazing discoveries.

AFOSR has contributed basic research funding to 82 Nobel laureates over the past 68 years. On average, these laureates receive AFOSR funding 17 years prior to winning their Nobel awards.

As a vital component of the Air Force Research Laboratory, AFOSR’s mission is to support Air Force goals of control and maximum utilization of air, space, and cyberspace by investing in basic research efforts for the Air Force in relevant scientific areas.

About the Author