The high school students founded the Committee to End Pay Toilets in America in late 1968 and launched what would be a tenacious, cheeky national campaign to get rid of the hated pay toilets.

“We were a bunch of high school — and later college — students who were angry at pay toilets and wanted to do something about it,” said Gessel, who is now vice president of federal programs for the Dayton Development Coalition. “Some students spend their time going to parties and drinking; we wrote model legislation and drafted press releases. Everyone has to have a hobby.”

For readers under the age of 50, thousands of public restrooms across the country had locking mechanisms on stall doors that required a dime or more to open. If you didn’t have any money — or the right change — you were out of luck or had to make a degrading crawl under the door.

The idea for changing the world came on a Gessel family road trip along the Pennsylvania Turnpike in December 1968 when the brothers encountered pay toilets at a Howard Johnson Restaurant. They saw it as an affront to human dignity. Ending pay toilets became a number one priority.

Ira penned an article that urged people to ask Congress to support legislation to ban pay toilets. Froikin printed the article in the Meadowdale High School student newspaper and the friends created the Committee to End Pay Toilets in America.

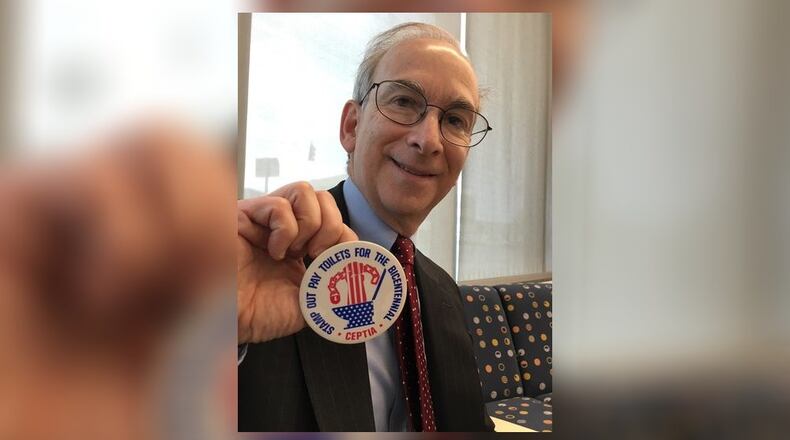

The logo was a fist clenching chains rising from a toilet bowl. “Ballad of the Pay Toilet” became the campaign anthem and “Ode to a Pay Toilet” — a poem — was read aloud at the first meeting, attended by 29 members at the downtown Dayton public library. Membership dues — 25-cents — streamed in from across the country.

Flush with gutsy ideas, they published “The Free Toilet Paper” and produced how-to guides for anti-pay-potty activists, wrote letters to newspapers editors, contacted elected officials and created the Thomas Crapper Memorial Award, named after the flush toilet inventor.

They started college campus chapters at University of Chicago, Kent State University, Johns Hopkins University, Harvard and elsewhere. That gave them a national footprint.

“We did what no one else before us had succeeded in doing, which was to move the debate from a pure joke to serious action,” Gessel said. “I think there was a window to do this. We were involved in the ’70s, it was the beginning of the feminist movement, then called women’s liberation, and 10 years later you had Ronald Reagan and a curtain of conservatism that came down. I think people would not have been open to the humor of it.”

The feminist movement bolstered the campaign, since urinals were free but sit-down toilets were not.

In February 1972, the committee made a big splash: an article on the Knight Newspapers wire that got picked up by multiple newspapers. A month later, the Dayton Daily News ran an editorial calling for removal of pay toilets at Cox Municipal Airport, where 34 pay toilets generated $11,400 in 1971.

In January 1973, they hit the mother lode of coverage: four newspapers, two TV stations, three wire services and several radio stations. Chicago moved to get rid of pay-to-go toilets.

“Everybody could relate to our cause and that’s why we were so successful,” Gessel said.

In May 1976, Ohio Gov. James Rhodes signed the toilet bill into law. It put a lid on the problem by requiring an equal number of free toilets for every pay one. A $1,000 penalty was tacked on for non-compliance.

With state after state enacting bans, and roughly half of the pay toilets decommissioned in the country, the committee declared victory and the Daytonians went on with their lives.

Ira Gessel is now a retired mathematics professor in Boston; Steve Froikin lives in Chicago and writes online training courses; Natalie Precker lives in Los Angeles; before his current gig with the development coalition, Michael Gessel worked for former U.S. Reps. Charles Whalen and Tony Hall.

Gessel said he doesn’t know of a public restroom or even a single stall named in honor of the committee or its founding members. The group’s exploits are mostly forgotten.

“This all happened in the days before the internet and a news story died when you took the newspapers out with the trash,” he said. “There aren’t many pay toilets left and I suspect many people today have never seen one. You don’t get much mileage talking about your campaign to eliminate pay toilets if people don’t know what you’re talking about.”

In a way, though, the campaign helped launch Gessel’s 40-year career in Washington.

As a college student, he applied for a summer internship with Whalen, then the congressman representing Dayton and Montgomery County. Thinking he needed something to stand out in a competitive field, Gessel listed the group’s effort on his resume.

He later found out that when Whalen’s aide, George Lowrey, saw the resume he said, “Committee to End Pay Toilets in America? We have to get this guy.”

About the Author