And the stakes are high. The results of the census help determine how billions in federal funding gets distributed and how much representation each state gets in Congress.

“Every 10 years there is a lot of concern about the funding for the census,” said Mark Salling, a census scholar and senior fellow at the Levine College of Urban Affairs at Cleveland State University. “But the cutbacks are much more severe now than in the past.”

RELATED: Miami Valley getting older, more diverse

The accuracy of the count is extremely important for Ohio, Salling said, impacting representation in Washington, social and human services that benefit all Ohioans, and business investment that determines where jobs get created.

“It’s a very big deal,” he said. “It’s an economic development tool.”

Funding uncertainty

Since the funding cycle for this census began, Congress demanded the 2020 census be conducted within the $13 billion cost of the 2010 census.

But Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross said in October that the 2020 census will require $15.6 billion, which includes a $1.2 billion emergency fund.

Changes have already been made reflecting the funding uncertainty. The bureau last year said it would not move forward with several test runs it was to conduct in Washington state and West Virginia, and instead would focus its resources on the April 2018 end-to-end test run that will be conducted in Providence County, R.I..

The scrapped tests would have been the only dress rehearsal of counting rural and remote communities including Indian reservation populations, according to a report by the Leadership Conference Education Fund.

RELATED: Flat growth in Dayton seen as good sign

“Shortchanging the Census Bureau is placing all of Ohio’s communities at risk of an inaccurate count,” said Ashon McKenzie, Children’s Defense Fund-Ohio policy director. “It could cost communities vital federal funding for health care, nutrition, education, and a host of other items.”

Undercounting could be extremely costly, said McKenzie. Young children, people of color, immigrants, and families in rural and Appalachian communities — groups that have been uncounted in past censuses — are all at risk of being missed at disproportionately high rates, he said.

Will Ohio lose clout?

One of the most visible impacts to the public from the 2020 census is what it will mean for Ohio’s clout in Washington.

The 2020 count will impact state congressional seats for the 2022 midterm elections, as well as electoral college votes for presidential races, beginning in 2024.

The latest projections from the consulting firm Election Data Services, Inc. show Ohio losing one congressional seat — dropping from 16 to 15 — because of population shifts in the 2020 census.

But experts say an inaccurate census could result in even more shifting of seats.

“If you get a good count in one state and not a good count in another, they might get a representative that they don’t deserve,” said Catherine Turcer, executive director of Common Cause Ohio, an elections watchdog group.

Once the number of seats is determined, it’s up to each state to redraw the lines of the congressional districts, also using census data to try and make each district equal in population. Although Ohioans voted to put a non-partisan redistricting commission in charge of redrawing of legislative district boundaries, congressional districts were not part of that ballot issue, leaving the drawing of those lines in the hands of the Republican-controlled state legislature.

RELATED: Ohio lawmakers may change how congressional lines are drawn

Common Cause Ohio and some other groups, under the banner "Fair Districts = Fair Elections," are gathering signatures to put an issue affecting congressional redistricting on the November 2018 ballot.

Turcer says an accurate census count impacts everything from having fair voting districts to planning for schools to giving private sector businesses the information they need about where to expand.

“If we don’t understand how many people there are, we can’t plan,” she said.

Accurate data ‘crucial’

Agencies that rely on federal funding have a huge stake in the census count.

During fiscal year 2015, more than 130 government programs used census data to distribute more than $675 billion in funds, according to the bureau.

In some cases there is a direct correlation between the census count and exact dollar amounts or designations.

The Stephanie Tubbs Jones Child Welfare Services grant, used by children services agencies to help keep families together, uses population data to determine its allotment beyond the base of $70,000 given each state.

For other agencies, the census provides data on which to make decisions about where services should be targeted and how best to communicate with the public. The Ohio Department of Transportation studies census tracts as part of the planning process for building new roads. Social service agencies like Head Start rely on it to bring in more dollars for needy families.

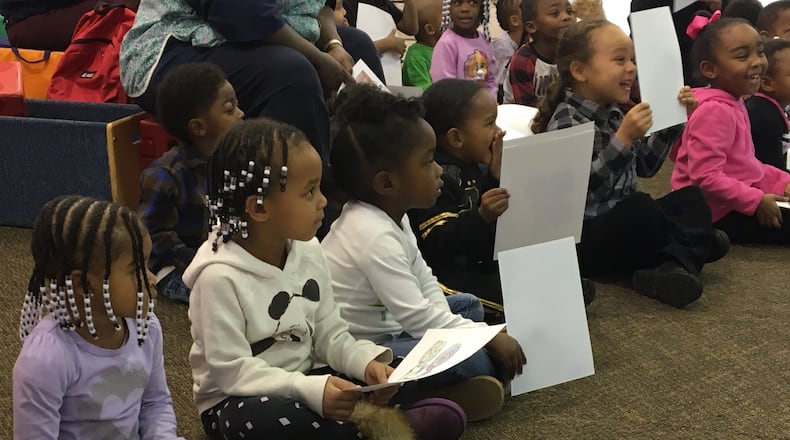

Past undercounts have hurt funding for Head Start, said Barbara Haxton, executive director of the Ohio Head Start Association.

“The sort of thing that gets collected in the federal census is crucial to the Head Start program design,” she said.

Clark County tract hard to count

Getting every person to participate in the census has always been a challenge, but growing distrust of government and unfamiliarity with the online form may pose additional hurdles this year, experts said.

Cuyahoga and Franklin counties, the two largest urban centers in Ohio, had initial participation — people who returned the mailed forms — below 75 percent during the 2010 census, as did a large swatch of Appalachian counties in the southeastern corner of the state.

Most of southwest Ohio had participation levels between 75 and 80 percent, with Warren County as the only standout at higher than 80 percent.

No counties in Ohio achieved higher than 85 percent participation.

RELATED: Today’s 30-year-olds less likely to be married, own a home

For every person who doesn’t fill out the initial form, the census sends out an enumerator to try and manually count that household — visiting the address between one and six times.

A census tract in southeastern Clark County was among those considered the hardest to count in the country in 2010, according to The City University of New York Center for Urban Research's "Hard to Count" study. The tract includes the village of South Charleston.

Fewer than 55 percent of households in that census tract mailed back their 2010 census questionnaire.

Census officials hope the online option will make a difference in areas like Clark County. In 2016, between 60 and 80 percent of households met the FCC’s minimum threshold for internet connectivity, according to the City University study.

‘It’s always been an issue’

Another obstacle is the people most in need of government services — the poor, the disabled, seniors and those with limited English proficiency — have the least access to the internet, according to federal data.

The Pew Research Center reports that as of late 2016, only 50 percent of people with disabilities reported using the internet on a daily basis, compared to 79 percent of people without disabilities.

For those areas that have little internet access, low computer literacy or significant language barriers, census enumerators will send out paper questionnaires or may simply go straight to the door-to-door option, the bureau’s plans say.

The question is, will the funding be adequate? As Turcer points out, “There is a significant cost to say, ‘Hey let’s knock on everybody’s door.’”

RELATED: What does a typical household look like? Census shows it’s changing

The online questionnaire has been optimized for mobile use, because census research shows smartphones are the only internet access for many households. But studies have shown that optimization does not eliminate higher break-off rates on phones — where people start the questionnaire, but never finish or submit it.

And fear of the government by immigrants — or those who think their information will be shared — remains a huge barrier.

Salling said the bureau is required by law not to divulge information on any individual or family, but is not always successful in communicating that information to the public.

“It’s always been an issue,” he said.

What does the census impact?

- The number of Ohio representatives in Congress. Ohio currently has 16 seats.

- The amount of federal funding allocated to some state and local government agencies and programs.

- The level of need for community services.

- Economic development decisions for businesses.

About the Author