Dayton is more connected than ever. But will it remain that way?

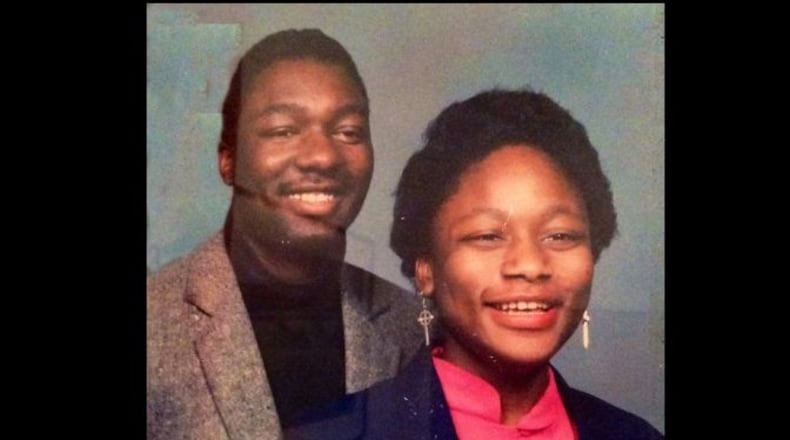

As my brother tells it, Vetta was trying to impress her big sister, Bip. "She said, 'come here Carl, give me a kiss,'" my brother told me.

He wasn’t puckering up. While making his escape, my brother smacked his head into a “No parking” sign pole next to the mulberry tree we all used to climb at the end of our grandparents’ street.

A knot formed on his forehead in an instant. "When I touched it, it busted right open." My brother's face was covered in blood when he made it to our apartment building around the corner, screaming that he thought he'd die.

I believed it. He was my wise older brother. He knew stuff. Our aunt Cathleen saw things differently. "She said 'shut up, you ain't dying.'"

Tornado changed everything, but mother vows: ‘I have to be strong’

She was, of course, right. My brother got stitches, but you can barely see the scar today.

It was the early ’90s the last time I thought my brother was going to die.

Carl was about 21. I was nearly 17. A stupid gripe and a bullet intended for someone else were the causes.

My brother and our cousin Nooky stood by that night as their friend JC worked on the headlight of my brother’s prized black Cadillac Coupe DeVille. They were in a familar place, the lot next to our grandparents’ house a stone’s throw from that mulberry tree.

AMELIA ROBINSON: Are you over it?

Our granddad held a light up so JC could see. A few minutes before flashes of fire came from the street, my brother walked down the street to our aunt Sharon’s house to get a bulb for the light.

On the way there and back, he saw three cars with young men in them.

He thought nothing of it until those cars drove by my grandparents’ house, sending lead into the night.

One of about six bullets fired from a .357 Magnum blew through the right side of my brother’s abdomen before lodging itself just two inches from his spine.

“It felt like you’ve been punched in the stomach. It felt like you got the air knocked out of you and then it was real hot, like you got popped with (hot cooking) grease — magnify it by 1,000.”

He tried to stop the bleeding with his hand. Our granddad had his .38 on him and returned fire, chasing the attackers off. My brother remembers getting into our cousin’s car, but it didn’t speed away.

Our granddad, also named Carl, was a big-bellied man with a union card and short legs. Our cousin had to adjust the car’s seat for him.

“He stopped at every light. I had to remind him that ‘I am shot.’ He was going like 30 mph.”

My brother remembers doing a sort of tuck and roll out of our cousin’s still-moving car when our grandfather finally made it to the hospital’s emergency-room lot. He remembers plopping into a wheelchair a man had retrieved for his elderly mother.

My brother remembers not wanting to take his hand away from the hole it covered. He remembers being barraged with questions from police as he was being prepped for surgery. He remembers being cold in the operating room and talking to the surgeon before being told to count backwards from 20.

“I asked him if I was going to die. He said, ‘I can’t tell you that. I don’t know.’ He could have lied.”

My brother guesses that he was just the latest body with bullets on the surgeon’s operating table.

“I guess he had seen so many that he got tired.”

DAYTON STRONG: The people who raised $5 million this summer for victims of the mass shootings and tornadoes

That was a long time ago, but I remember praying in the waiting room that night that my only brother wouldn’t die.

The doctors told us he could have.

Thousands and thousands of sisters have thought their brothers were going to die from gun violence since the day I thought I would lose mine.

The Centers for Disease Control says 39,773 people died from gun-related injuries in the United States in 2017, the most recent year for which statistics are available.

I remember all those times I prayed in my car years later before going in homes to talk to the families of shooting victims as part of my job as a crime reporter.

“Please, God, let me tell this story the right way. Please, God, let them know my intentions are good.”

Please, God, let them know that their son, father or brother matters.

I often think about the 10-inch scar that has run up my brother’s stomach since that night in the early 1990s.

He shouldn’t have it. No one should have those kinds of memories.

Far too many do.

About the Author