By the second night, the high-rise apartment complex a few doors away had been hit by Russian rockets. On the street out front was the mangled remains of a Russian tank blown up by Ukrainians trying to defend their city, which is in the southern part of the country, just off the Black Sea.

Within 48 hours war had engulfed the home of Andrey Arkhipov and his father.

“His name is Vladimir – it’s the good Vladimir,’” Arkhipov said with a tired laugh.

Life for the father and son, like the rest of Ukraine, had forever changed.

For decades the Arkhipovs were bonded most by basketball.

Vladimir had played professionally and then coached and managed top pro teams in Ukraine. One of his teams toured North America, playing the NBA’s Toronto Raptors and college teams like the Miami Hurricanes.

Andrey – already 6-foot-4 by age 14 – captained Ukraine’s Under-16 national team for three years, played in tournaments around Europe and eventually ended up at a Christian high school in Miami, Florida.

After a serious knee injury derailed his recruitment by several Division I schools, he came to Cedarville University where, from 2000 to 2004 he was a popular 6-7 forward.

I remember going to a game there once when his fellow students – all from the same dormitory – became his exuberant fan club.

They sat just beyond the basket, each wearing a letter from his name or his jersey number they had painted on their white t-shirts. They called themselves Akhipov’s Army and they cheered everything he did.

But now, just over a month ago, the Arkhipov’s lifelong interest in hoops was suddenly eclipsed by the horror of war.

Since Feb. 24, the Russians have waged a continued assault on their city, which is the gateway to Odessa, 80 miles to the west and the headquarters of the Ukrainian navy and the country’s largest civilian port.

Ukrainians have regularly fended off their invaders, but the price has been steep.

Russians have bombed indiscriminately – attacking everything from a kindergarten, a crowded market and a hospital to hotels, civilian neighborhoods, a military barracks were young soldiers were sleeping and even an orphanage bus.

Ukrainian officials said the Russians have used banned cluster munitions and the Mykolaiv morgues are filled with bodies stacked like cordwood.

“It’s been really depressing,” Arkhipov said. “I really didn’t expect this. Until the last minute, I was thinking: ‘There’s no way the Russians will do something like this.’

“There are Russians on this side, especially in the South. It’s a complex history, but basically it’s like they’re bombing their brother’s house.”

Russians are intent on capturing the Varvarivsky Bridge, which is in Mykolaiv and is the only passage for miles across the wide mouth of the Southern Buh River. It provides easy passage to Odessa.

Though the Russians, who’ve brought troops up from Crimea, have an advantage in manpower and ordnance, they continually have been stymied and Arkhipov fears her frustration could lead to the kind of long range missile attacks that have leveled Mariupol.

In the early days of the siege, Arkhipov said his father, who had been teaching at a university, had been tasked with guarding international students in the basement of their dormitory until they could be airlifted to safety.

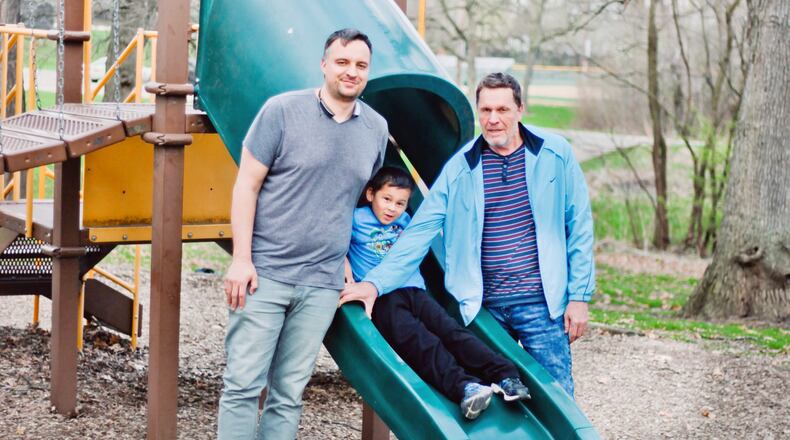

Before the Russian attack, Arkhipov – who now runs a multi-media production business and lives in Davenport, Iowa, with his wife Eleanor, 10-year-old son Maksim and 4-year-old daughter Valeska – sent money to his father so he could buy provisions.

But once the fighting began and conditions worsened, he begged his father to leave.

Men between the ages of 18 and 60 are required to stay and fight and Vladimir – even though he’s 67 – stayed until, in Andrey’s words, things were “almost unbearable.”

He finally began the dangerous trek to Moldova, arriving there six days ago and becoming one of the over 4 million people who have fled Ukraine.

As his dad was leaving, Arkhipov asked him if there was someone else he knew who needed immediate help.

His father suggested a young family with small children and a newborn baby. They were especially vulnerable.

Arkhipov and his sister, Marina, who had played college basketball at St. Leo University in Florida, raised $4,000 and with the help of Northwest Christian and the Music Mission Kiev charity – which was launched 30 years ago by a Xenia High music teacher and his wife (both now retired in Warren County) – they got the family to Moldova and Friday brought them to Ireland.

Vladimir has now made it to New York City and soon will head to Seattle, where Andrey’s mother lives, too.

While the family is safe, friends back home have been killed, many more have been uprooted and the nation is being decimated.

“It’s been like stepping into a different dimension,” Arkhipov said. “All of a sudden the world is about you…in a bad way. It’s just unbelievable.”

Hoops journey to the U.S.

From the time he was 13, Andrey said he was often away from home, travelling and training in various Ukrainian cities as part of the national team.

When he was 15, he said the point guard on his team had planned to go to the United States to play basketball and get a high school education. The boy’s parents asked Arkhipov – since he spoke English – if he would go along to make their son’s transition easier.

He agreed, but when it came time to go, the other kid didn’t have the proper paperwork to enter the U.S.

Arkhipov came on his own to Northwest Christian Academy in Miami.

The team was coached by Tony Pujol, who later became an assistant coach on Anthony Grant’s staffs at VCU and Alabama and now is the head coach at North Alabama.

Arkhipov soon began to showcase himself with his prep team – they won the state title – and with an AAU team coached in part by Frank Martin, Grant’s former high school teammate, longtime friend and now the new head coach at UMass.

Arkhipov – also a good student – drew interest from several D-I schools and said he planned to go to Yale. But senior year he tore his ACL and interest dried up.

That opened the door for Cedarville – then coached by Ray Slagle – which was recruiting another Northwest Christian player and learned of him.

Although he would deal with various injuries in his college career, Arkhipov made a name for himself at Cedarville.

Freshman year he had several big games – 23 points against St. Mary’s, 20 against both Wittenberg and Bryan College – and that led to birth of Arkhipov’s Army, whose shirts spelled out “A-N-D-R-E-Y #44.”

In the classroom – here he pursued visual effects and cinematography studies – he was especially proficient in a cutting edge, 3D animation software that he’d been introduced to while taking classes at Barry University as a high school student.

He said he ended up student teaching a class at Cedarville on its usage.

He praised his time at the school and the numerous mentors he had there. That helped him land a job in Iowa as a producer on an animated kids’ series.

Along the way he’s worked with the NBA and NHL and he’s currently a partner and CTO of Flixpress LLC, which offers web-based video templates to create a low cost, customized multi-media tool.

He stays in contact with several of his former Yellow Jacket teammates – especially David Dingman – and said he’s heard from many in the Cedarville community since the Russian assault began.

Since he came to the U.S. as a teenager, Arkhipov said he has been back to the Ukraine just once, in 2011, and now he wonders what he’ll find if he ever gets a chance to go again.

‘He’s a great leader’

Each day he follows intently – and heartbreakingly – what transpires in Mykolaiv.

He is inspired by the presence there of Vitaliy Kim, the charismatic governor of the region and a former classmate of his.

An inspirational leader, Kim posts upbeat videos each day on Facebook and Telegram. On them he smiles, flashes the peace sign and often denigrates the Russians calling them idiots, bastards and orcs, a reference to the evil goblins from Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings.”

He wears a black pistol holstered to a belt and sometimes drives around in a captured Russian Tigr armored vehicle that he has painted with the blue and yellow Ukrainian flag.

“He’s a great leader,” Arkhipov said. “He’s got a great sense of humor and a lot of people say he’s the only reason they’re staying sane. He’s been truly heroic through all of his.”

Kim’s also encouraged people to stack old tires on each street corner and then have an incendiary device nearby. That way, if Russian armored vehicles or troops enter the street, locals can light the tires on fire and the black, choking smoke will blanket and blind the invaders and give locals a chance to attack them.

In the future, Arkhipov sees two possible scenarios unfolding in Ukraine:

“The troops Putin sent in didn’t seem to know what they were going in for. They were told it was for training and then they were told to attack. They expected to be met with arms wide open and instead it was ‘You’re on our land. Why are you shooting our kids? You are the enemy. Get out!’

“Now they’re forced to try to manage things and so they must lie to their own people on why they are there.

“That’s the most frustrating part, especially because here in the United States some people are buying into that. It’s infuriating. How can you align with a guy like that?

“He breaks into your home, shoots your children and then says ‘Hey, it’s your fault. You stood next to them!’

“Ukrainian people will fight to the end. They’ve lost all their initial fear and now are just angry. The Russians, I’m afraid, will try to completely level and demoralize our city like they’re doing to Mariupol.”

And what is Scenario 2?

He hesitated, then offered quietly:

“It will be a nuclear hostage situation. And it will become an enormous humanitarian crisis.”

Asked what average Americans can do to help, he suggested two things:

“First, you can read and educate yourself.”

And he didn’t mean listening to those right wing commentators, politicians and social media types who are parroting Putin’s lies.

Arkhipov also stressed “getting involved” as he and his family have done, first in helping the young family get to Ireland and now assisting others in need.

He suggested the Red Cross and more specifically for him, two organizations he believes are doing real good:

Music Mission Kiev (musicmissionkiev.org) was started in 1992 by Roger McMurrin, the former Xenia High music teacher and his wife Diane.

They were brought to Kyiv to conduct Handel’s “Messiah” to musicians who, under Soviet rule, had never heard the music before. They started the Kyiv Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, did 10 tours through the Unite States and, with the funds collected, they started two churches and began to provide financial help for widows, orphans and those displaced by war.

Arkhipov also is working with Central Park Angels, a non-profit out of New York City that has organized volunteers on the ground in Poland. They are helping refugees with logistics and have been helping feed some 5,000 people in camps each day. (youaretheangel.org).

“In my mind, if I can help one family I know I’m doing something,” he said. “It just feels like a very human connection at time like this.”

With that in mind, it seems like it’s the right time to revive – and expand – Arkhipov’s Army.

All of us can join, though this time, rather than hoops, it’s all about help.

About the Author