He was the back judge in a game between Fairview and Belmont, where a similar scene unfolded with a far more deadly consequence.

“As I was watching Monday night, the first thing that came to my mind was what happened to that Pickens boy in our game,” Allen said. “It was over 42 years ago and I’ve never forgotten it.”

Paul Beyerle — a longtime Miami Valley educator, coach and for 40 years a high school, college and NFL football official, including 25 years in the collegiate Mid-American Conference — was in the Paycor crowd Monday night and eventually his thoughts went to that 1980 game, as well.

His late father, Joe Beyerle, was the head referee that night and his son knows the incident spurred him to do something quite remarkable afterward.

And down in Lake Worth, Florida, Jim Musson was watching the Bengals game with his wife and told her about that 1980 night when he was the umpire on an officiating crew at Welcome Stadium and a 16-year-old boy named James Pickens had been similarly hurt.

“Harold Allen and I were on either side of the boy after the tackle,” Musson said Saturday morning. “Harold reached down like he thought he needed help up, but from my angle I saw he wasn’t breathing right and said, ‘Harold, no! Don’t touch him.’

“We yelled for the trainer and by the time he got there, we knew it was bad. We screamed for the ambulance and they drove out on the field and loaded him up and took him away.”

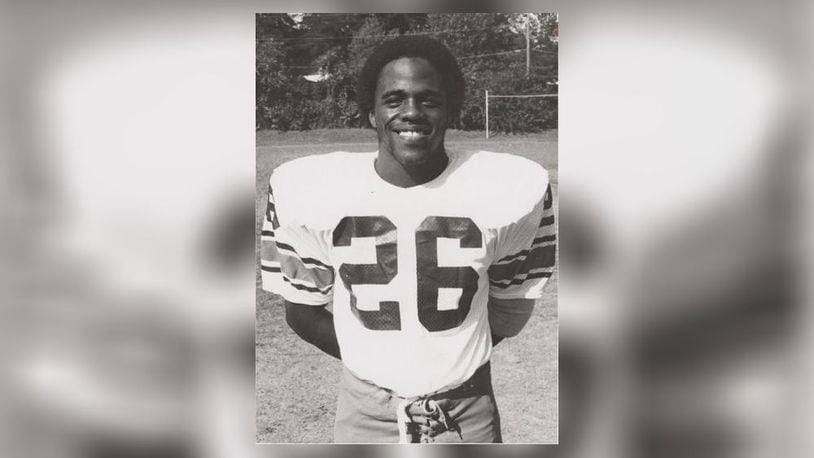

Pickens was a superb football talent at Fairview, an All-City linebacker and a hard-nosed junior running back who could lift the team on the shoulders of his well-muscled, 5-foot-9, 195-pound body.

“They called him Little Earl Campbell,” his twin sister Janine recalled Friday evening.

Gene Winters, the late Fairview coach, was just as lofty in his praise to reporters back in 1980:

“He was the most versatile player I ever coached. On a scale of 1 to 10, he was an 11. He was just one of those types of athlete you look for, an ideal ballplayer and student.”

Mary Pickens, the late mother of James and Janine, told Chick Ludwig of the Dayton Daily News:

“(James) once told me, ‘Mom, you won’t have to worry about money for my college tuition. I’m going to win a scholarship.’ ”

“Yes, indeed. There’s no doubt in anybody’s mind he would have gone pro,” said Janine, now a housing manager for St. Vincent de Paul. “He was that good.”

He played three sports at Fairview and was part of the 440-yard relay team that qualified for the state track championships.

Off the field he may have been even more impressive. A good student and popular, he was elected to the Fairview Homecoming Court in each of his three years of high school.

“James was a born leader in a very special way,” Fairview’s late principal, Jean Booker, said back then. “He had a quiet kind of confidence and set a great example for his teammates and all of our students.

“He looked you in the eye and meant what he said. He had integrity. He was a gentleman. And he had the spirit when others were down.

“And he loved Fairview.”

That night at Welcome Stadium – October 23, 1980 – he led Fairview to a 14-0 upset of Belmont.

He was a one-man wrecking ball on defense, returned kicks and powered the Bulldogs’ running attack on offense.

It was an exhausting effort and in the third quarter it seemed to catch up to him.

His brother Fred was at the game and told Ludwig afterward:

“James was rockin’ (tackling) pretty solid all night. He made two or three real hard tackles in the third quarter, all of them low, right around the thighs with his head and shoulders.

“There were about three minutes left in the third quarter and he came out. He was walking up and down the sidelines, holding his head. He’d kneel or squat and then start walking again.

“He jogged down the track, then put his helmet back on. There were about two minutes gone in the fourth quarter when he went back in.

“Fairview intercepted a pass and returned it to the 20- or 30-yard line.

“They gave the ball to James and he ran down the middle to about the one-yard line and got hit.”

Like Hamlin on Monday night, he popped back up, took a step and then collapsed.

There was 2:27 left in the game.

He was unconscious when he was carried into nearby St. Elizabeth Hospital where Dr. Jose Duarte performed a four-hour surgery to try to repair a brain aneurysm.

Janine, who’s now 59, remembers people congregating at the hospital and at their Kipling Drive home.

In the days that followed, as Pickens lingered in a coma, the family got messages from around the country – Florida, Texas, New York, Nevada, Kentucky, Indiana – and even Germany.

While there were many similarities with the Hamlin situation, one thing was terribly different.

In recent days, the Bills safety has defied odds and is alert and showing signs of recovery.

Pickens did not.

He never awoke and on Nov. 6 — two weeks after he was injured and 12 days before his 17th birthday — he was pronounced dead.

Services were held at Shiloh Baptist Church and he was buried in West Memory Gardens.

Then, like now, people wanted to do something good in Pickens’ name and the five-man officiating crew — led by Joe Beyerle — did something extraordinary.

“We got a trophy to honor him,” Allen remembered.

The following year it became the centerpiece of the Fairview-Belmont match up, which was renamed the James W. Pickens Memorial Game. Engraved on the award was: “To the best of sportsmanship, the power of faith, the spirit of teamwork.”

“My dad had a heart of gold,” said Paul Beyerle. “He was very empathetic to others. He believed we were all united by the game of football – coaches, players and officials – and this was a way to reach out to the pain that was felt by the Pickens family and Fairview High School.”

‘I love the contact’

James Pickens Sr. was a truck driver for DPL and his wife Mary did contract work at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. They had 10 kids and while many were athletes, the twins showed special sports prowess.

Janine played volleyball, basketball, softball and ran track. James played basketball, was a sprinter and started playing varsity football as a freshman.

“As far as personality, I was an introvert and he was the extrovert,” she said

Booker told how the other students looked up to James for the way he was in the classroom and the school hallways, and especially on the football field.

But early in his junior season, he was injured in a loss to Edgewood and was hobbled when the Bulldogs played Roth and were embarrassed, 62-0.

“Every person I came in contact with knew I played for Fairview,” Pickens told Ludwig. “I’d walk down the street and they’d laugh. Well, I promised myself it wouldn’t happen again if I could help it.”

And in an early October game against Meadowdale, he played the entire game and rushed for 109 yards. He ran back kicks and punts and made 21 tackles on defense.

“I wasn’t coming out,” he said after the Fairview victory.

“I love football. I love the contact. Something about football excites me. That’s how I get my high.”

But just 22 days later, that contact — as the Montgomery County Coroner ruled – would lead to his death.

While Janine usually went to her brother’s games and he came to hers — “We supported each other,” she said —she said she wasn’t at Welcome Stadium that night:

“I think it was a God thing. I wasn’t meant to be at that game that day.”

She played in a volleyball match after school and then came home. Her mom wasn’t at the game either. She was flying back from Stuttgart, West Germany, where an older brother was stationed in the Army.

When her mom called from LaGuardia Airport, her dad told her everything was fine and that he and a couple of family members were headed to the game.

When Mary finally got home – unaware of the tragedy – she was met at the door by Janine who, according to an interview back then, frantically told her: “Mom, you’ve got to go right now to the hospital! It’s Jay. He’s got a blood clot.”

In the ensuing days, James’ situation got more dire.

“We go one minute to the next not knowing,” his dad said. “It’s very depressing.

“We’re going to go along with what the doctor says, but we’re not going to let him live on a respirator forever. I don’t go along with having a machine keep him alive for six months

“If he definitely can’t make it, we’ll take him off the machine. Whatever you do you will have people who disagree. But that’s our feeling.”

When James passed away, his mother said:

“We’re just so glad the good Lord saw fit to call him home and not let him remain here as a vegetable. Knowing him and loving him as we have, we know he would not have wanted that.”

Afterward James Sr. said: “I guess all fathers say this, but he was a good boy. I don’t blame anyone. Not football, Not the coach. No one.

“He was doing what he loved and that may be the best way for him to go. The only way better would have been if he’d been praying.”

Janine said she and her school were “just devastated. It was a horrific event for everybody at my school, especially since my brother was so well thought of.”

Homecoming was the week after James was hurt and Teresa Dalton, who had been his partner on the court for each of the three years they been chosen, was in tears at the Homecoming Court presentation.

She walked alone.

And when it came to the Homecoming dance, assistant principal Lou Galiardi came to the rescue and danced with her.

Soon the crowd was in tears.

Parallels with tragedy

“The guys who played for Belmont and were involved in the tackle took it very hard,” Janine said. “I was able to meet with them and I told them we knew it wasn’t their fault.

“And Coach Winters took it real hard, too.”

He blamed himself and told Ludwig afterward, “I’m so doggone choked up by this. I haven’t been functioning.”

For him, the loss was compounded by another nine years earlier.

In 1971, Victor Dixon, a standout Fairview basketball and track athlete, had collapsed and died in a basketball game during a gym class run by him.

Although the Pickens family saluted Winters in their editorial letter, the longtime coach retired after the season.

Before the memorial game in 1981, the trophy the officials had gotten — “it’s really neat what they did,” Booker said, “it will help remember the very best of what James stood for”— was displayed at both schools and then at Welcome Stadium before the game, which Belmont won, 16-12.

Pickens’ parents both came to the game. His dad wore his letter jacket and his mom wore a blue and yellow corsage, Bulldog colors.

“They had our crew work the game again and they had a ceremony with his parents at halftime,” Musson said. “I thought that was very brave of them. I don’t think I could have done that.”

A year later, Fairview closed for good and Janine said she’s never seen the trophy again.

But two things from that tragedy 42 years ago were evident again in the Hamlin situation the past week.

Just as people have continued to give to the modest toy drive the Bills safety started for kids two years ago in his hometown —Saturday afternoon the fund was over $8.2 million — people, in more modest, but just as heartfelt fashion, reached out to the Pickens family.

And they responded in a letter that was published on the editorial page of the Dayton Daily News. It ended with: “If any of your readers don’t believe this is God’s beautiful world filled with countless people who care, they need to contact our family.”

Paul Beyerle, who spent four decades officiating football games, brought up another truth.

He said people watching on TV or even up in the stands “don’t really know how violent the game of football is.”

For that, he said, “You have to be out on the field.”

And that’s where James Pickens and Damar Hamlin ended up lying.

About the Author