On Nov. 5-7, the school will host its first Roger Brown Residency in Social Justice, Writing and Sport. Celebrated author and journalist Wil Haygood will conduct this session.

Last fall, a commitment like this wasn’t on the radar of anyone, especially Davis, the nationally-acclaimed artist and educator who was helping install an exhibit of 30 pieces of work by local African American artists in the University of Dayton’s presidential residence on Ridgeway Road, a home now occupied by Dr. Eric Spina and his family.

But when Davis got to one especially significant piece by James Pate, he hesitated.

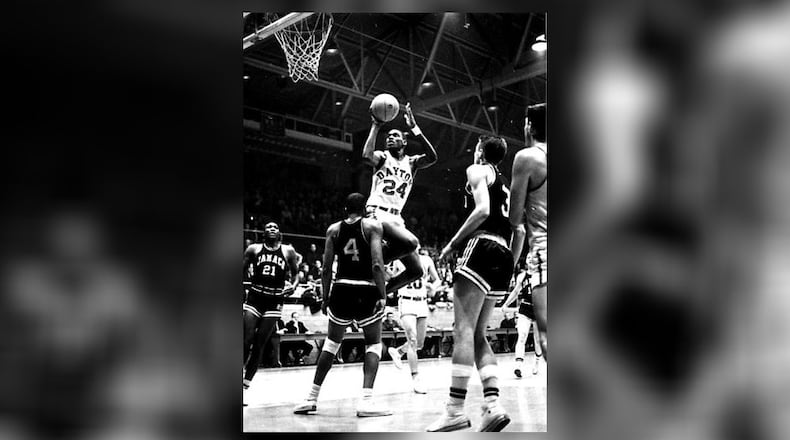

The work – described as “Blackballed Totem Draw of Roger ‘The Rajah’ Brown” – was a collage of images that included everything from a portrait of Brown in his No. 11 UD jersey and a picture of him soaring to the hoop as an Indiana Pacer to the modest house on Shoop Avenue where he had lived in exile with Azariah and Arlena Smith, the West Dayton couple who became his saviors.

“We brought that piece in the house and I was worried,” Davis admitted. “I was thinking, ‘I don’t know if I want to put this piece in this house.’”

After all, Brown had been abandoned by UD more than a half century earlier and he had been ignored by the school since.

But Davis decided to hang the piece in a place of prominence and he said when Spina saw it “he had a good reaction to it.”

At the time, Spina had been the UD president for just over two years, but he’d learned a little about Brown thanks, initially, to Davis. The two men had become friendly and talked over lunch on occasion.

Once a great athlete himself and a friend of Brown’s who had played basketball with him in the Dayton industrial leagues, Davis had brought up how Brown had been unjustly smeared in a gambling probe of college basketball.

Others speculated that UD had quickly abandoned Brown back then in hopes of currying favor with the NCAA on a different infraction issue.

Brown and his fellow Brooklyn pal Connie Hawkins – who had gone to Iowa – ended up banned by the NCAA and the NBA, though the pro league would eventually pay a $2 million court settlement for its actions.

After years of struggle here in Dayton, Brown — thanks to a helping hand from NBA great Oscar Robertson – was signed by the Pacers and became an ABA legend. A few years ago he was enshrined in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

Still nothing happened at UD until a dinner party last fall at Spina’s home to honor the authors and several other people involved in the Dayton Literary Peace Prize gala which would be held the following night.

Among the guests were Davis and Haygood, whose book “Tigerland” is a finalist for this year’s DLPP award.

As the evening progressed, Davis gave Haygood a tour of the exhibit and Spina noticed they had considerable conversation in front of Pate’s Roger Brown work, a piece that had become one of his favorites, too.

“It makes Roger more physical, more real,” Spina said.

Credit: Larry Burgess

Credit: Larry Burgess

Later the three men all ended up at the table together.

“We were just shooting the crap, talking sports and other things and Wil said how some of the things he was hearing about Roger paralleled the stories of some of the players on the 1968-69 Columbus East team he portrays in Tigerland,” Davis said,

Spina said the more they talked, the more one thing became clear:

“We went from, ‘Well, it’s good for Roger to be visible here in the president’s residence’ to ‘I really think it’s time to make him visible at the institution and in the community.’”

Davis agreed, but didn’t get his hopes up. Over the years people — especially in West Dayton where Brown was once a cult hero — had tried to get the university to pay tribute to him.

After Brown’s death from liver cancer in 1997, the Smiths had led a campaign in local churches, collecting signatures on a petition that was presented to the university, but never acted upon.

Davis hoped this would be different – he had a good feeling about Spina – but he still wasn’t sure:

“You never know. It’s like a lot of conversations in a social setting like that. You have a drink in one hand, you make promises and later you’re not sure if it’s the drink talking or it’s real.

“I just didn’t know what to expect.”

Well, he does today and he sums it up with one word:

“Wow!

“With all he’s involved in, this never left his mind. He called an academic committee together and they came up with this. It’s more than I ever dreamed of.”

Brown’s son, Roger Jr. – now a defense contractor living in Maryland following an 18-year career in the Army – is just as overwhelmed:

“I’m ecstatic. It’s a great gesture … one that was long overdue.”

In an interview in his St. Mary’s Hall office the other day and in a university press release today, Spina agreed:

“Roger Brown was one of the greatest basketball players ever to attend the University of Dayton and he’s still highly regarded in the Dayton community 22 years after his death, but he has been invisible at the University of Dayton and that is neither right nor just.”

Spina acknowledged the role the school played in Brown’s struggles after his UD ouster and said he “deserved better than to be abandoned by the university. … This residency is intended to be a lasting testament to Mr. Brown’s tenacity, excellence, grace and commitment to doing what is right.

“This is going to be a gift that gives for generations. Overall, what I want our students to get from this is an opportunity to understand you can look for injustice anywhere and look for ways to try to right that injustice.”

Gambling scandal

Brown and Hawkins – both from the Bedford Stuyvesant section Brooklyn – were considered the two best schoolboy athletes in New York City in 1960 and among the five best in the nation.

At UD, Brown became part of the school’s most fabled recruiting class, joining Bill Chmielewski, Gordie Hatton, Chuck Izor and Jim Powers on the freshman team since first-year players weren’t eligible for the varsity back then.

The team packed the Fairgrounds Coliseum for its games and ended up the national AAU runner-up. The following season – minus Brown – the Flyers won the prestigious NIT tournament.

But in the summer before coming to UD, Brown and Hawkins had been approached by gamblers Jack Molinas and Joe Hacken. Brown was given $200 to introduce Hacken to players on the playgrounds and he was allowed to drive Molinas’ car.

Investigators later found he had no contact with either man after coming to UD, was not involved in fixing games and neither were any of the players he had introduced to the pair.

But because a gambling scandal was smearing the college game – 28 athletes, 17 schools and 39 games were singled out by authorities – the feds squeezed Brown and Hawkins in an attempt to get more dirt on Molinas and Hacken, both of whom eventually would get prison time.

Brown’s involvement with them came to light when he returned to New York to appear in traffic court for a summer accident he had driving Molinas’ car. He and Hawkins ended up held for four days in a hotel room with no lawyers present and no phone calls allowed.

Though Brown was never charged with anything, the NCAA discovered Dayton had paid his way to New York three times to go to court. Facing sanctions, UD, some say, jettisoned Brown in hopes of a lighter penalty. The shabby treatment was compounded by a couple of high profile media people in town who pilloried Brown.

But some of those closest to Brown strongly disagreed.

“Roger was a great guy. He got a raw deal,” Chmielewski once told me.

And before he died, Herbie Dintaman, the Flyers freshman coach, said: “Roger was robbed. The decision came quick and from way higher up than me.”

Brown was crushed and didn’t know where to turn.

The Smiths – who had no children of their own – took him in. Azariah got him a job at Inland and got him on the factory’s industrial league team he helped coach. Arlena even taught him how to dance.

But before he passed away a few years ago, Azariah – who had made a museum in his basement dedicated to Brown’s accomplishments – told me how they had gotten threatening letters and phone calls telling them to get Brown out of their home.

He said at night Brown had had recurring nightmares and would cry out: “Please, I didn’t do anything, Please! Please!”.

Brown lived in Dayton six years and later, after he reached stardom, he continued to return here and even funded a program for children in foster care.

After his playing career ended and the Pacers retired his number, he stayed in Indianapolis where he was the assistant coroner, a city councilman and a mentor for Pacers’ players.

Just a few weeks before he died, I interviewed him for the last time. His breathing was labored and his voice was weak and I thought we should cut the conversation short, but he wanted to make sure I understood a few things.

He talked about his love for Azariah and Arlena and he repeated one thing to me twice.

“I love UD…I still love UD.”

‘Final piece of his … ordeal’

Haygood, like Davis, commends Spina for leading the effort to recognize Brown and discuss the role of sports and social justice:

“I think President Spina is a very forward-looking president. He has a progressive mindset. And I think it is incumbent of leaders of higher education to look more closely at what’s happening on the streets coast to coast when it comes to race in this country. I think it’s an extremely important time in our nation’s history to talk about these things.”

Haygood – a Miami University grad who lives in Washington D.C. but serves as a Boadway Distinguished Scholar-in-Residence with MU’s Department of Media, Journalism and Film – talked about athletes using their platforms for social justice and how many, including Brown, seem to rise the occasion:

“I think a lot of goodness was exemplified by Roger Brown. He suffered a setback and yet he rose from the ashes.”

Bing Davis likes the educational component that comes in Brown’s name:

“This is more than just putting a picture up in the Arena or giving him a mention somewhere. This will contribute to society in a positive way in his name. I was just hoping to get a formal apology and get his name cleared and have it spoken in a good breath on campus.”

Roger Brown Jr. agreed: “It’s ’s a tremendous honor. At the hall of fame speech, I said his journey was now complete. But actually it was not because UD wasn’t involved in that.

“This is the actual final piece of his whole ordeal.”

And that brings us back to that art exhibit last year.

In his office the other day, Spina walked off and returned with a large, framed piece of artwork that he held backwards so you couldn’t see what it was.

“First some show and tell,” he said as he turned the piece around and beamed.

It was Pate’s Roger Brown work.

Spina and his wife Karen had liked it so much they bought it.

“Originally, I talked with Neil (athletics director Neil Sullivan) about doing something in the Arena,” he said. “But my wife and I think it should be somewhere on campus

“There are many more lessons here than him just being a good basketball player.”

About the Author