It was Friday, May 7, and Carroll High School – where Gerhard was a former wrestler, longtime assistant coach and is in the school’s Athletic Hall of Fame – was hosting the USA Wrestling-Ohio Greco/Freestyle State Qualifier on Saturday.

Some 400 wrestlers from around the state were coming in for the tournament and Gerhard, like he so often was, was the event director.

For more than four decades, he’d done everything he could to develop and promote youth and high school wrestling in the Miami Valley and beyond. He did it, friends say, because he wanted to give young people the building blocks you can get from the sport. Things like character and discipline and self-confidence.

Wise said Gerhard knew a lot of that from his own life experiences and the things he learned as a wrestler at Carroll and then Wright State University:

“Mark lost his dad when he was still pretty young and I believe wrestling and the things he got from it helped him.”

Jim Kordik, a teammate of Gerhard and Wise when they all wrested for WSU in the mid-1970s, agreed: “Mark’s father passed away while we were in college and he continued to live at home to help raise his eight younger siblings.”

In 1978, Gerhard and Wise started the Raiders Wrestling Club for area youth and within two years they were mentoring 200 young wrestlers.

Gerhard launched the Patriots Wrestling Club three years later and then began the Miami Valley Kids Wrestling Association in 1986. It eventually grew to 70 teams across southwest and northwest Ohio and involved over 3,000 wrestlers.

“It became the largest kids’ wrestling program in the country,” Kordik said.

“Mark’s strength was helping kids,” said Jason Ashworth, Carroll’s head coach who was a Bellbrook wrestler when he first met Gerhard. “I was from another school, but it didn’t matter. He’d find me opportunities to wrestle and I’d come and train with the Carroll guys sometimes. Mark didn’t care what school you were from. It could be Beavercreek, Fairborn, Fairmont, Troy Christian, anyplace.

“He just wanted to help everyone get better.

“Mark was a helper. A real helper.”

He helped kids become high school stars and college wrestlers and, in the process, develop the traits they could rely on later in life with their jobs, their families and their own ongoing growth.

“For more than 40 years I watched Mark’s dedication to the sport and to children here,” said Kordik, who was a two-time MVP of the Wright State team and is in the school’s hall of fame. Today he’s an attorney with Rogers and Greenberg.

“Mark never sought anything for it. Not recognition, not compensation. Nothing. He just had a burning desire to do good for others. He was a doer of good things, not a talker.”

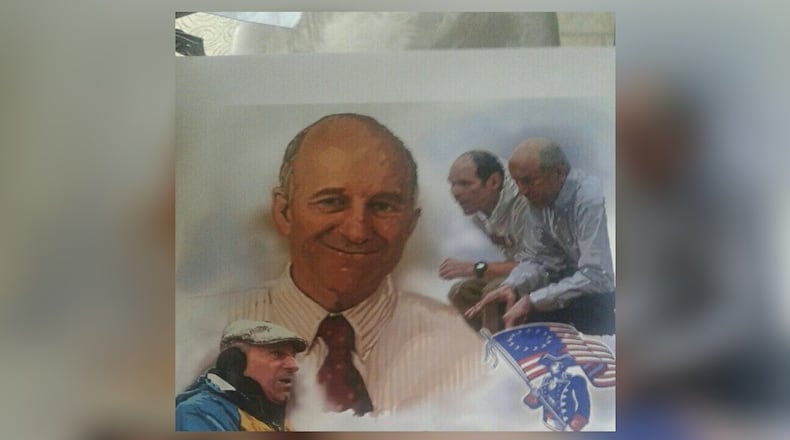

His contributions to the sport and most importantly the young people he nurtured are the big reason he is being enshrined today in the National Wrestling Hall of Fame. He’s receiving the Lifetime Service to Wrestling Award at a banquet in Columbus this afternoon put on by the Ohio chapter of the Oklahoma-based Hall.

And in 2022, he’ll be inducted into the Ohio High School Wrestling Coaches Hall of Fame at the state wrestling finals.

“There is no one individual in the Miami Valley who impacted more lives than Mark Gerhard did,” Wise said quietly, his voice beginning to break.

“I’m glad I finally found him that night, but when I did, I realized right away, ‘Oh my gosh! We’ve got a problem.’”

Seven weeks later, his friend was dead.

‘Just a great man’

“I remember the first day he came out for the team,” said Stamat Bulugaris, Wright State’s former wrestling coach. “It was late October. We’d just finished conditioning and were getting ready to start our mats when he approached me and said he wanted to wrestle.

“Our guys had just finished the 3-mile run and I said, ‘Well, you’ve missed all our conditioning and you’ll have to run a 3-mile course before you do anything.’

“He looked at me and said, ‘Well, I can do that. I can do it right now if you want me to.’”

Bulugaris was skeptical: “Now? You can run your 3 miles right now?”

Gerhard told him “Sure.”

“I didn’t know he had been on the cross country team,” Bulugaris said. “That’s how his college career began.”

In 1978, Gerhard, who wrestled at 134 pounds, scored the first points ever for Wright State in an NCAA national tournament.

“It was the third period and he was losing his match,” Bulugaris remembered. “But then he took the top and put on that cross-face cradle of his. He looked over at me and just smiled.

“He always was a pinner and he cranked the kid over and pinned him down.”

Gary Wise also was a 134-pound wrestler and he and Gerhard practiced together and competed for spots in the lineup, sometimes with Bulugaris moving them to different weights so both were on the match card.

In the process Wise and Gerhard became best friends, a bond that lasted over four decades.

With the various wrestling clubs that Gerhard launched, he mentored and nurtured the careers of thousands of area wrestlers.

Jeff Clemens said he started out in the Patriots Wrestling Club when he was in first grade.

A Carroll, where Gerhard was an assistant, Clemens compiled 131-34 career record and, as a senior, was 42-1 and won the state title at 189 pounds. He went on to wrestle at Michigan State and then returned to Carroll – were he’s in the hall of fame – to coach for three seasons.

Gerhard was his assistant, too.

Now an engineer for Konecranes in Springfield, Clemens won’t forget Gerhard’s impact:

“He was always trying to get people into the sport, no matter what their skill level. He was always positive, but very humble and selfless, too.

“He was quite amazing, really. Just a great man.”

‘The most genuine human being you could ever find’

On May 7, Ashworth was feeling pre-tournament organizational jitters. Hundreds of wrestlers were headed to Carroll and that day he found out one of the mats that should have been dropped off had not been delivered.

Immediately after school he had to go across town to get another mat and he called Gerhard – who in his years as a Carroll assistant had been a systems analyst for Reynolds and Reynolds – to see if he could come to the school early and help look after the Patriots athletes and handle any early arrivals for the next day’s tournament.

“He said he’d be here in five minutes,” Ashworth remembered.

But he didn’t arrive for five hours.

That was not like Gerhard at all. He was conscientious, organized, meticulous, so much so that he once was known as Coach File Cabinet.

When Gerhard was a college wrestler, he was so fastidious he sometimes was teased by his fellow Raiders, said Bulugaris, who also coached at UD and Beavercreek High School and now leads the seventh grade team at Beavercreek Middle School:

“Every time we’d go to eat as team, he’d order a cup of tea. Then he’d pull out his own teabag and a stop watch so he could get the exact amount of time the teabag was in the hot water.

“Everything was exact.” But that Friday, when Gerhard finally did show up at Carroll, he was not himself.

Bulugaris said his son and grandson, who was wrestling in the qualifier, arrived from Columbus for the Friday weigh-ins and had a troubling conversation with Gerhard:

“My son said, ‘Dad, I saw Mark, He talked to me, but he was a little incoherent. He seemed lost.’”

Gerhard left again and things got more chaotic said Ashworth: “Mark was the tournament director and I didn’t know how he had set a lot of things up. It was a crazy night.”

As concerns grew, Ashworth tried calling Gerhard’s cell, but couldn’t reach him. Finally, Ashworth’s wife contacted Gary Wise and explained the situation.

“I kept calling and calling Mark and finally he picked up,” Wise said. “I said, ‘Mark, where are you?’ There was a little hesitation and finally he said he thought he was around UD.

“I said, ‘Mark, you have a tournament to run tomorrow. There’s no reason you should be driving around.’ I could tell he was confused and I told him to find a gas station, pull in and then tell me where it was and I’d meet him there.”

Wise finally found his friend at a gas station on the corner of Linden and Smithville.

“He got in my car and I could tell he was in trouble,” Wise said. “We drove straight to the hospital.”

The conversation that followed was heartbreaking.

“He said he was concerned because he was having some of the same problems his mom had had and she had passed away from a brain tumor,” Wise said. Gerhard’s diagnosis was crushing.

He had glioblastoma, which is considered he deadliest form of cancer. It aggressively and often evasively attacks the brain and Gerhard had large brain tumor that doctors said was inoperable.

Wise stayed with Gerhard, while Ashworth, reeling from the news, did his best to run the tournament without the man who always had done it so masterfully.

“Really, it was a nightmare that day,” remembered Ashworth, whose step counter tallied the 48,000 steps he took that day. “The one thing is our wrestling community is pretty tight and everybody pulled together to make it happen.”

Gerhard was moved to the Carlyle House and his brothers and sisters rallied around him as did the wrestling community.

“He was dignified the whole time,” Kordik said. “He didn’t complain. He was just such an admirable person.”

Gerhard died on June 26. He was 66.

Today, the wrestling community will celebrate him at his hall of fame induction.

“He was a tremendous role model – for all of us,” Ashworth said. “He was always helpful and caring and just so kind.

“He was the most genuine human being you could ever find.

“I really miss him.”

About the Author