“I wasn’t very old and I remember standing on the front car seat between my mom and dad. We’d get to the light at Germantown and Euclid and it would hold so ungodly long that I’d get to see at least two or three race cars being towed past on their way up Germantown hill to Dayton Speedway.

“Those cars were so colorful and they had those big numbers on ‘em and I was fascinated. To me that said, ‘Fast!’”

He chuckled and added: “My wife says I probably was overstimulated as a kid, but I came from a family that liked speed.”

He said his dad, Elmer, had been a Tuskegee Airman in World War II – “he was a gunner on a B-26,” – and later he had his own plane here.

As for his mom, Glenna: “We used to call my mother Hot Rod. Oh she could drive. She could flat out wheel!”

Sometimes the family went to watch races at Dayton Speedway and for Steve the love affair deepened:

“At a young age I knew it was a sport for white folks, but that didn’t matter really. The cars were more fascinating to me than the color of the people driving them. I focused on how fast those cars went.”

Later Ross had a football career of note at Chaminade High School and that got him a scholarship to Bethune Cookman College in Daytona Beach, Fla., which also happened to be the home of the Daytona 500.

While in college, he got a job as a Saturday morning DJ at a white radio station. The owner got him a press pass to the 500 and that’s where Ross first met his idol, Wendell Scott, the only African-American driver in the NASCAR Cup Series.

Eventually Ross transferred to Ball State and then Central State. And while he’d later work as a therapist, school teacher, coach and community activist, he continued to embrace race cars.

He competed at various Southwest Ohio tracks in 1970s and ‘80s and early on found out color did matter to some folks.

“I heard the names and the jokes,” he said quietly. I didn’t let that bother me. I was there to race.”

But once at the Queen City Raceway in West Chester that was impossible. Another driver purposely crashed Ross’ car through an outer guardrail and sent it airborne toward the stands.

“Buddy, they were trying to kill you,” another guy there told him.

Incidents like this aren’t exaggeration.

I covered stock car racing in the 1970s and 80s when I worked in Florida and I witnessed some incidents like that first hand.

Some of those events have come back to mind for me — and Ross, too – with some of the recent events surrounding Bubba Wallace, who, like Scott 40 and 50 years earlier, is the only African-American competing on the Cup circuit.

Earlier this month the 26-year-old Wallace – who had a crowd of 20,000 roaring at Eldora when he won a truck race there six years ago – finally found his voice following the killings of a pair of unarmed Black men by whites that was captured in two heart-sickening videos that soon went viral and sparked national protests.

Wallace first urged his fellow drivers to speak out against social injustice – and they did in a group video — and then a few days later got NASCAR to ban the divisive Confederate flag from its races, something the governing body already had been toying with since a white supremacist killed nine blacks in their church five years ago in Charleston, S.C.

Last Sunday before the Geico 500 at Talladega Speedway in Alabama, a crew member of Wallace’s discovered a noose fashioned at the end of the pull rope on the team’s garage door at the track.

Wallace didn’t see it because in these COVID-19 times, not only have fans mostly been kept from attending races, but a driver’s time in the garage is severely limited.

The crewman reported the noose to NASCAR officials who – knowing the polarizing, sometimes-threatening times we now live in – called in the FBI.

Meanwhile, NASCAR did some investigation of its on. It checked all 1,684 garage stalls at its 29 tracks across the nation and found only 11 had pull down ropes tied in a knot.

And only one – the one said to have been arbitrarily assigned at Talladega to Wallace – was tied in a noose.

The race was delayed by rain on Sunday and before Monday’s restart the rest of the drivers and their crews escorted Wallace’s car down pit row.

A day later the FBI announced Wallace had not been the target of a hate crime. It said the noose had been there since a race at Talladega in October.

Immediately, Wallace was pilloried on social media – sometimes in ugly, racist fashion – saying he made the story up to promote his own cause.

NASCAR and almost everyone else involved debunked those claims.

Still that didn’t deter guys like former Major League pitcher and broadcaster and current right wing provocateur Curt Schilling from blasting Wallace in a since-deleted tweets. Fox News host Tucker Carlson was even more tendentious.

And then there was Mike Fulp, the owner of 311 Motor Speedway in Stokes County, N.C . who advertised “Bubba Ropes” for sale on Facebook, claiming they “work great.”

Most chilling though was Dustin Skinner, the former NASCAR truck competitor and son of longtime driver Mike Skinner, who posted on Facebook:

“My hat is off to who put the noose at his car…Frankly I wish they would have tied it too (sic) him and drug him around the pits.”

Under fire, Dustin Skinner apologized for his comments.

Wiggins, Wendell and Willy T.

“Whenever that noose was put up, it was probably some kind of cruel joke,” Ross said. “But if it was left up since October, how many people looked at it and just left it? It sends the wrong message. You know what it represents. A noose represents hanging.”

The Equal Justice Initiative says from the end of the Civil War to just after World War II, there were over 4,000 lynchings of Blacks in America.

Often those murders came with all forms of torture and drew community gatherings of white people who celebrated and sometimes made postcards of the hanging black person.

And while most of those lynchings happened in the south, the Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Ala., lists seven that occurred in the Miami Valley.

It was against that backdrop that some Blacks came to stock car racing even though the American Automobile Association, which initially governed the sport, banned them from driving.

Instead Blacks raced in things like the Gold and Glory Sweepstakes. Its early star was Charlie Wiggins – known as “The Negro Speed King” – but at one prerace qualifier at Kentucky Speedway in Louisville in 1920, a white mob burst through a fence to protest his presence on what they considered a “whites only” track.

Police were called in and they arrested Wiggins, saying they could only keep him safe in jail. That night they smuggled him out of the city.

When he got out of the Army after WWII, Wendell Scott began racing and eventually fashioned a Hall of Fame career. He ran 485 races and had 147 Top 10 finishes. That becomes more impressive when you consider he never got any real sponsorship money and many times he faced harassment …and worse.

I interviewed Wendell once late in his career and he told me about the regular threat he got from the Ku Klux Klan and how he was banned from restaurants and motels. His grandson Warrick, CEO of the Wendell Scott Foundation, tells how he was poisoned before a race.

Then there’s the soul-crushing story of his lone victory at the Jacksonville 200 in 1963.

When he crossed the finish line, Scott was two laps ahead of second place Buck Baker. But officials — knowing the winner was traditionally kissed on the cheek and photographed with the white race queen – suddenly announced there had been a scoring error.

The real winner was Baker, who got the kisses, the photo and the trophy.

Scott secretly got the winner’s check a few hours later and in 2010 – 30 years after Wendell had died from cancer – his family was awarded a duplicate trophy.

I remember outspoken Black driver Willy T. Ribbs showing up to race in the mid-1980s and seeing a pair of race fans spit at his feet as he came through the crowd. And it was just 20 years ago when two pit crew members were fired for wearing white Klan hoods in the garage to intimidate a black crewman.

It’s figured only eight Black drivers — in 72 years of racing – have started a race in NASCAR’s Cup Series. Before Wallace – who did finish second in the 2018 Daytona 500 and third at last year’s Brickyard 400 – the last driver was Bill Lester in 2006.

Lester will soon team with Steve Ross in an innovative venture here in Dayton – as well as in Detroit, Atlanta and Los Angeles – that they hope develops young drivers of color as a sort of a minor league farm system for NASCAR.

The announcement, waylaid by the coronavirus epidemic, should come in July, Ross said.

Still a long way to go

While some people are viewing the events with the noose as everything from an overreach to an utter fiasco, I see it differently.

To me NASCAR was thinking first and foremost about the safety and well-being of one of its drivers.

More importantly I think it showed Wallace’s fellow drivers in the best light of all as they marched down pit road Monday to support him.

“I never dreamed I’d see anything like all that,” Ross said, “But then I didn’t think it would take a noose to do it either.”

While NASCAR has made a push for diversity in recent years, Ross said the sport still has a long way to go.

Just like with Scott before him, Wallace is the only African-American in the Cup Series. And like Scott his car has no major corporate sponsorship.

“Look we buy M & Ms and pie and Cadillacs and Chevrolets and Buicks, but corporate America doesn’t reciprocate,” Ross said.

“And they need to help more drivers of color find a path to the top (tiers) of racing.”

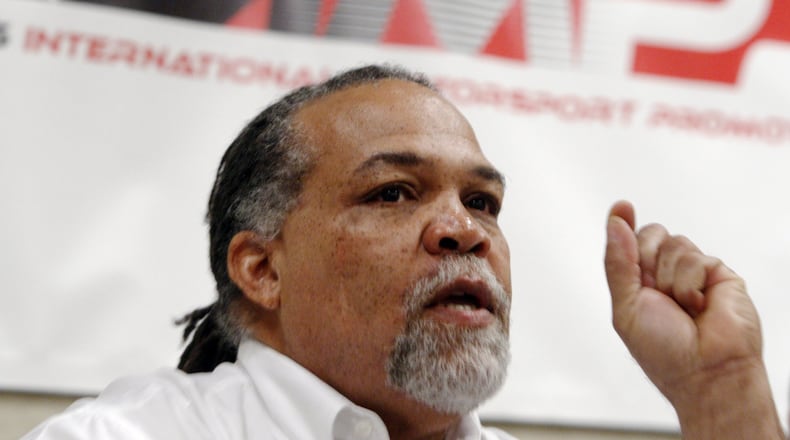

Throughout his life the 67-year old Ross has gravitated back to racing.

Several years ago he and others launched the Spirit 4 Racing program to promote young minority and girl drivers. Next month he and seven others will unveil their plans to begin the driving academy for people of color.

He wants young drivers to have it easier than he did, especially on that night at the Queen City Raceway when his car was knocked out of the track, hit a pole, ricocheted back across the racing surface and broke in two when it hit the inside retaining wall.

He suffered one cut,

but shrugged it off and said he’d race again. That’s when the guy from the stands offered him a car, minus an engine, for $800.

Secretly taking $800 out of the family checking account, Ross hid his new purchase at his uncle’s farm.

Meanwhile, his wife, Karen, went to pay the utilities bill and, not knowing their meager bank account had been drained, wrote a check that bounced. A couple of days later Ross returned home to find their place dark.

The electricity had been shut off.

He and his family had to temporarily move in with his parents who, he now laughs, told him:

“You’re a damned fool.”

Getting to stock car heaven when you’re a Black driver – whether you’re Steve Ross, Wendell Scott or now Bubba Wallace – never comes easily.

About the Author