“We were out on the playground, playing basketball, and the game got a little rough,” Green recalled. “There was a guy who was a little cocky and we had a little altercation.

“He was going in for a lay-up and on the playground you got punished for that. And I kind of took him into the wall.

“Well, the guys who played with us kind of chuckled, but the kid wasn’t feeling so good and after a while he picked up a nice sized rock, threw it and hit me in the back. Once again, the guys started laughing.

“The kid took off running and he was pretty fast. I chased him and he ran past the office and the principal was there. When I came rushing in, the principal said: ‘Whoa! What’s going on here!’

“I said that kid hit me with a rock and now I’ve got to get him back.’ I was intent on getting my hands on that kid, but the principal said, ‘You just can’t run into my office to ‘get some kid! That’s enough. You need to go home.’”

Green trudged home and suddenly found himself face to face with reality.

“I’ll never forget it. It was a Wednesday and my dad was off on Wednesday afternoons.”

A 6-foot-3, 250-pound truck driver, his dad was sitting on the porch when he walked up:

“I told him the principal had just thrown me out of school.”

Soon Ernie’s mom, a no-nonsense woman who had raised six kids, was at the door and told her husband to march Ernie back to school.

Green said the principal told his dad: “Ernie just got a little rambunctious. All I want you to do is to take him back to his homeroom, take him into the cloakroom and put a strap to him!”

His dad was intent on doing just that until Ernie’s teacher – “she was very, very nice,” he remembered – intervened and said: “‘I don’t think that’s necessary. Ernie is not a bad boy. I’m sure he will never do that again.’”

At the last moment, his dad acquiesced and Ernie learned a lifelong lesson:

“That’s the last time I ever did anything like that because I knew my father wouldn’t stand for it. After that I became a model citizen. It was something I never forgot.”

Time and again he showed that in his life:

>At Spencer High – then an all-black school in the days of segregation – he not only was a stellar football, baseball and basketball player, but he was senior class president and a member of the National Honor Society.

>A two-sport star at the University of Louisville — which he said was one of the first colleges below the Mason Dixon line to accept black students — he kept his composure when facing racial taunts from rival fans and excelled even more on the field of play.

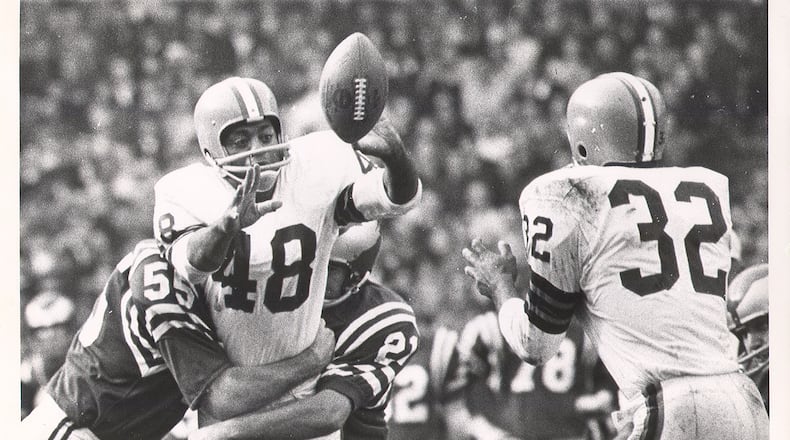

>After entering the NFL in 1962, he soon showed he could swallow his ego and make sure his backfield mates with the Browns — first Jim Brown and then Leroy Kelley — had success.

Although he became a two-time All Pro himself at running back and won the NFL title with the Browns in 1964 — a season where he led the team with 10 touchdowns — Green made his biggest impact as a blocking back.

With Green providing the protection, Brown ran for a then-NFL record 1,863 yards in 1963.

After Brown retired, Green then blocked for Kelly, who led the NFL in rushing in 1966 and had three straight 1,000 yard seasons

In the process, Green became known as “The Other Guy.”

He laughed about it the other day: “I’d go out in the community and introduce myself and folks would say, ‘Oh yeah, you’re the other guy in the backfield with Jim Brown.’”

>The lessons of his childhood and football served him especially well when in 1981, he partnered with Sam Morgan and they launched Ernie Green Industries, which was based in Kettering, initially manufactured components for the automotive industry and later the medical industry and other fields. Eventually EGI had as 15 plants based in several states, Canada and the Dominican Republic.

And their success wasn’t just based on their entrepreneurial insight, but the bond between them.

Two men who at first glance might seem dissimilar — Morgan is white and from Eastern Kentucky ,East Dayton and Stivers High; Green is black from southern Georgia and then pro football — they became consummate business partners and lifelong friends who are both now in their 80s.

Their connection had a lot to do with the love and respect they had for their mothers. Green said Sam’s late mother, Mae Morgan, reminded him of his own.

“He just loved my mother,” Sam said.

Mae felt the same about Ernie.

“If you’re around Ernie and get to know him, you can keep but liking him,” Sam said. “We’ve worked together over 40 years and never had a major argument. He is one heck of a good person.”

>Other people here agreed. In 2010, at the National Philanthropy Day gathering at the Schuster Center, Green and his wife, Della, were named the area’s “Outstanding Philanthropists” for their work with everything from the Dayton Boys and Girls Club, and the Dayton Contemporary Dance Company to the American Red Cross, the Dayton Urban League, Central State University and other groups.

CSU honored him with an Honorary Doctorate of Letters because he was “a role model exemplifying the values of honesty, hard work and excellence.”

Credit: Dayton Daily News

Credit: Dayton Daily News

Two-way player at Louisville

Although a high school football star in the South, Green was bypassed by the powerful SEC schools whose segregated teams had no black football players until 1966, eight years after he graduated.

Louisville did invite him up, but in quite unceremonious fashion.

After getting advice from his parents — his dad stressed working hard; his mom, he said, told him to “Keep your nose clean…and don’t come home” — he boarded a Greyhound bus at 5 a..m, one day.

It was his first trip away from home.

“Obviously, back then I had to ride in the back of the bus,” he said. “I remember as we drove through Atlanta and then Chattanooga and Nashville, I was thinking: ‘All the schools we drove past won’t take African American kids.”

He arrived at the Louisville bus station at night. There was no one there and he admits he was scared and contemplated going back home until his mom’s voice filled his thoughts.

He eventually got a coach’s phone number, called and someone was sent for him.

For part of his Louisville career he played both ways. He was a linebacker and a running back and in his final two seasons rushed for 1,500 yards and got All America recognition.

Morgan said Green was just as good of a baseball player and the Detroit Tigers were interested in him.

Teams weren’t just impressed by his size — 6-foot-2, 205pounds — but his composure.

That especially showed once in a baseball game at Eastern Kentucky University.

He was playing third base for the Cardinals and the EKU fans were seated nearby.

“I was the only kid of color on our team and the fans were sitting almost right up on us,” he said. “They gave me fits all game. They called me everything but a child of God.

“They were trying to upset me because I was a pretty good player, but I didn’t respond. I just ignored them. "

He let his play speak for him and afterward he said he simply got on the bus and went back to Louisville:

“The fact that I was able to do that taught me things I could draw on throughout my life.”

NFL career

When the Green Bay Packers, the NFL’s reigning champions, drafted him in the 14th round of the 1962 draft, Green said he initially wondered why. Then he figured Coach Vince Lombardi “wouldn’t waste a pick on a guy he didn’t think could make the team.”

He threw himself into being in top shape and learning the Packers’ system and played in the first two preseason games: first against the College All Stars and then in Dallas against the Cowboys,

The following morning he said there was a knock on his hotel door. A Packers assistant told him he was being summoned to Lombardi’s room.

“I thought, ‘My God, Nooo! I’m being sent home,’” he recalled. “But when I got to Lombardi’s room. he told me to be calm. He said, ‘I’m not cutting you.’

“And then he told me a story how he and Paul Brown (the coach of the Browns) were best of friends.

“He said, ‘We’re trading you to Cleveland.’ The Browns had drafted Ernie Davis out of Syracuse, but then he was diagnosed with leukemia and Lombardi told me he was probably never going to get a chance to play.

“He said, ‘If you go and demonstrate to them what you’ve demonstrated to me, I believe you can play. Good luck to you.’”

Green flew into Cleveland and was brought to meet Paul Brown, who, he said, had just a few initial words:

“He looked at me and said, ‘Vince Lombardi thinks you can play, so get yourself together.’ And then he walked off.”

Green got himself together and had seven seasons with the Browns before an ACL injury ended his career in 1968. He finished with 3,204 career rushing yards, 2,036 receiving yards and 35 touchdowns.

In 2012 he was enshrined in the Cleveland Browns Legends Association.

Never making more than $50,000 a year in the NFL, he worked other jobs in the offseasons, everything from a probation officer in Elyria to a buyer for the old Halle’s Department Store.

After football he tried a couple of different fields. He was an assistant Vice President of Student Affairs at Case Western Reserve and the executive director and vice president of the IMG Team Sports Division.

Morgan said he got to know Green through their Louisville connections. Sam’s older brother Jim was a superb basketball player for the Cardinals. And the Olsen brothers — Bud and Bill — had been Louisville stars. Bill played baseball with Ernie and later served as the school’s athletics director.

In 2005, Green was diagnosed with breast cancer, had a mastectomy and became a spokesman for the cause.

Since his surgery, Green said he has difficulty when the weather is either very cold or very hot, so he lives May to November in Kettering and the rest of the year in Ormond Beach, Florida, where EGI has one of its plants.

Today when the Browns play he Bengals he hopes to watch the game on TV.

Credit: AP

Credit: AP

Browns and Bengals fan

While he’s been tied to the Browns for six decades and has a special appreciation of their loyal fans, he also has respect for the Bengals.

He initially played for Paul Brown, the founder of the Bengals, and said he knows his son Mike, the longtime president of the Cincinnati team, very well:

“I’ve been in Mike’s company a few times and more and more he looks and sounds like his dad. I’m really proud of the relationship I have with him. He’s done a great job with that organization down there.

“And I’m excited for his team. I adore (Joe) Burrow. I love watching him with his teammates. He seems like a nice young man.

“But, and I don’t know if I should say this, (Burrow) has never had much luck with the Browns. You know they’re the team he rooted for when he was growing up and maybe there’s just something there about beating them.”

Today — like every Sunday — he’ll pull for the Browns though he admits it’s not always an easy task:

“When you get involved with the Browns, it’s just like you have one or two children who go crazy periodically. But at the end of the day, they’re still your children and you still love them.”

He said a Browns Backers club in nearby St. Augustine has been trying to get him to come up to watch a game with them, but he’s been reluctant.

“If I’m watching the game, I don’t want somebody watching me yelling and screaming and going crazy,” he laughed. “I don’t know if I want to embarrass myself like that.”

He never needs to worry about that.

Whether it’s been in the Browns’ backfield; with his friend Sam Morgan and their Ernie Green Industries; or with his Philanthropist of the Year charity work, he’s never embarrassed himself.

They might have called him “The Other Guy.”

But to those who have known him the longest, Ernie Green always has been “The Guy.”

About the Author