Abdul Shakur Ahmad, the star point guard of Jackson’s first team – the 1975-76 Raiders – said the coach’s wife, Corinne, told him her husband died from Alzheimer’s complications.

“On our first day of practice with him, I remember they rolled out the ball cart and there was a placard on it saying, ‘Team goals: 20 wins, NCAA Tournament bid,’” said Ahmad. “And every day after that, when we went in, we saw that.”

Although those were marks never before achieved in the young program, Ahmad – who was known as Rick Martin during his WSU days – said he and the other two returning senior starters, Bob Grote and Lyle Falkner, were determined to make them happen.

John Ross had coached the team its first five years and in his last three seasons the Raiders went 17-5, 17-8 and 15-10.

“Even before Marcus got there, we had decided we were going to the NCAA Tournament,” said Ahmad, who was a team captain and the Raiders’ co-MVP his senior year. “We all felt we should have gone to the Tournament in our junior year.”

When Ross moved up to a newly formed assistant athletics director job at the school, WSU hired Jackson from Dartmouth College, where he had reinvigorated a moribund program in his one season there.

But he really had made his name before that, at Coe College in Cedar Rapids, where he became the first African American college coach in Iowa history.

In his three seasons there, his teams went 66-14. The second year the Cohawks went 22-0 in the regular season, led the nation in scoring (91.2 points per game), made the NCAA Division II Tournament and finished 24-1. The following year his 18-5 team averaged 92 points per game.

In 1997 he was enshrined in the Coe College Hall of Fame.

“I’m very honored what Coe has done for me today,” he said at his induction. “I have great respect and love for this school.”

Disappointing ending at WSU

Although Ahmad said Jackson was “the most organized man I ever met,” and that first team made history – collectively and individually – the coach’s tenure and parting sentiments at Wright State were not the same as they were with Coe College.

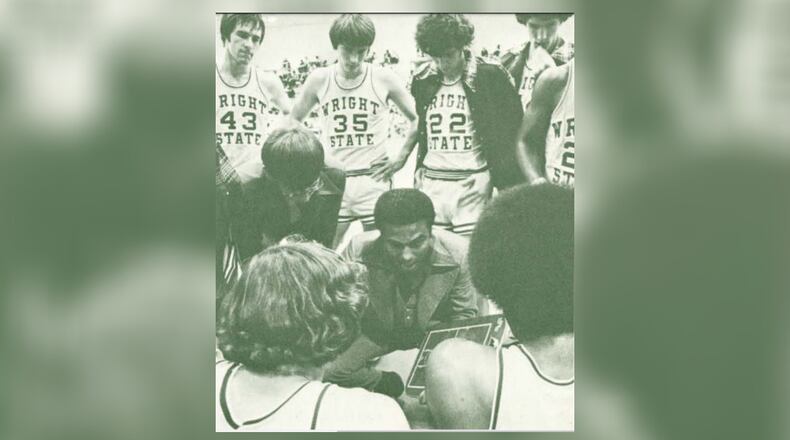

In Jackson’s first WSU season: the Raiders went 14-0 at home; Bob Grote became the school’s first basketball All American; and after an invite to the NCAA Division II Tournament, Wright State lost to Evansville in the regional opener, but defeated St. Joseph’s in a consolation game.

They ended the season 20-8. The following year they stumbled to 11-16.

But the third year they started out strong, going 13-5 and at one point were ranked No. 13 in the nation among NCAA Division II programs. They then lost eight of their last nine games.

One of the final losses came with an especially heated backdrop. It was the second last home game of the season and rival Northern Kentucky came into the old P.E. Building gym wearing gold uniforms, the color the Raiders wore at home.

The teams have the same colors, and NKU’s head coach Mote Hils knew WSU always wore gold at home.,

Jim Brown, now the Raiders color commentator on radio broadcasts, but back then one of Jackson’s assistant coaches, thought the NKU coach didn’t get along with Jackson and dressed his team in gold to irritate him.

The Raiders were forced to go back to the dressing room and alter their uniforms. Brown said they ended up wearing green jerseys and gold pants.

“We looked like we were in the circus,” Brown said.

Jackson was angered not only by the NKU disrespect but, Brown said, by what he felt was athletic director Don Mohr’s failure to back him up in the dispute and a heated argument between the two followed.

Wright State lost the game 77-73 in overtime.

After the Raiders coaches returned from clinics and watching the Final Four in St Louis, Jackson and his other assistant, Jerry Holbrook, were fired.

Brown, who had coached previously with Ross, was not.

“I was shocked when they decided to let Marcus go,” said Brown who would go on to spend 27 years on the Raiders sidelines.

Mohr, who hired and fired Jackson, claimed his decision was based on “unsatisfactory progress” in the program even though Jackson had a three-year record of 45-37.

The split left everyone bruised.

Jackson and Holbrook, who was white, publicly suggested discrimination was a factor in their departure.

“Basketball was not in the decision to fire me,” Jackson told the Dayton Journal Herald. “Compared to others, my record was on top…. We (he and Holbrook) felt discrimination was involved in our firing.”

Mohr disputed that: “There wasn’t any discrimination involved. If there was, why would I have hired the two in the first place?”

But Holbrook claimed something didn’t add up:

“It was odd. We go to a national tournament and, all of a sudden, they won’t renew our contract.”

There was the threat of a civil rights lawsuit and at the behest of the university’s affirmative action advisor, the WSU Athletic Council did a second review of the matter.

Although it stood by Mohr’s decision, the school — according to a July 1978 report in the Dayton Journal Herald — did pay Jackson $15,000 to drop the lawsuit. Holbrook received $6,000.

Jackson told the Journal Herald if he had not gotten the financial settlement, he would have pursued the suit.

The messy ending also cost Brown his shot at becoming the Raiders head coach in 1978.

Three days after Jackson was fired, Brown said he was told by Mohr the school was going to hire him as the head coach. When the threat of a lawsuit surfaced, the offer to Brown was rescinded.

Unfortunately, Brown said, the affair also hurt his relationship with Jackson:

“Marcus surmised I had something to do with it since I didn’t get fired and our relationship soured. But I truly didn’t. I was stunned when he was fired. I liked him.”

Brown recalled “a really nice thing” Jackson did for him and his wife Becky:

“When Becky was pregnant with our youngest son, he had this surprise baby shower at his home.

“Every media person was there – all the sportswriters and the radio and TV people. It was really, really nice.”

‘We did make some history’

After Jackson was fired and the offer was pulled from Brown, Wright State hired Ralph Underhill, who had been successful assistant coach at UT Chattanooga.

Brown stayed on as his assistant and great success quickly followed.

WSU went 20-8 in Underhill’s first season and made the NCAA Tournament.

In Underhill’s first nine seasons at WSU, the Raiders averaged 23.2 victories per season, went to seven NCAA (Division II) Tournaments and won the national championship in 1983.

After WSU, Ahmad said Jackson owned four successful McDonald’s franchises in Dayton and later owned a General Nutrition Centers (GNC) store in Florida.

Jackson died in Leawood, Kansas.

“Marcis was special,” said Ahmad, who ended his career with 1,182 career points and remains second on the all-time steals list at WSU. “He was quite a person. I enjoyed playing for him. We had a very good team.”

And that leads to one thing that needs to be rectified from that tumultuous time so many decades past.

“I’ve asked many times why that team hasn’t been recognized by the university,” Ahmad said. “We did make some history at the school.”

Honoring that team is long overdue and it would make a far better epitaph for Marcus Jackson and his days at WSU.

About the Author