Edwin Moses said he was in the third or fourth grade when his dad first was brought him to the meet and the spectacle soon had him spellbound:

“In those days, when the person leading the hurdles race crossed each hurdle, the whole crowd would go “woooooph!”

By 1973, he was a small, slightly-built senior at Fairview High School who wore glasses, had a gap in his front teeth and nothing especially distinguishable on his track resume. He was known for his academic achievements and egghead pursuits — science fairs, playing the saxophone, reading, once collecting butterflies and fossils – not grabbing the attention of a high-decibel track crowd.

But that spring he made it into the finals of the 110 high hurdles at the Relays.

Jim Crutcher, the Ponitz track coach who ran track at Colonel White back in the 1970s, recalled the atmosphere back then:

“The Relays were huge. They ran them on Friday nights then and if you weren’t here by 4 p.m. you didn’t get in the stadium. The parking lot was filled and cars parked all around Stewart Street, all the way up to (U.S) 35. And the stands were overfilled. It was really a scene.”

Now a half century later, Moses still remembers that 1973 race, start to finish:

“I got out of the blocks a little behind everybody, but by the third hurdle I was moving into position and things were about even through the sixth hurdle. Then I started to move ahead and every time I went over a hurdle, I heard ‘woooooph!’

“I was leading and the crowd was chanting ‘woooooph!.... woooooph…..woooooph!’

“I won and to me it was like winning the Olympics. I’d never thought I was good enough to win anything and here I’d just won the Dayton Relays.

“It was the first major race I ever won and I remember going home and telling my mom and dad I’d won.”

As the memory came back to him, he started to laugh: “I’ve still got the medal I won that day.”

As everybody now well knows, after that he won enough medals — Olympic, World Championship, World Cup. Pan American Games — plaques and trophies to fill a museum.

He became Dayton’s most celebrated athlete ever and one of the city’s all-time favorite sons.

After he won gold in the 400 meter hurdles at the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles —part of his mind-boggling, 10-year, 122 consecutive race unbeaten streak in the event — he returned to Dayton and he and his wife where the centerpiece of a parade through downtown. As they rode in a convertible along streets filled with cheering crowds, they were surrounded by 1,000 school children waving American flags.

He was similarly embraced around the world, a point once underscored in Taiwan when he was training by himself and a crowd of 5,000 gathered to watch.

Now 67 and looking as fit as he did when he dominated the Olympic stage — winning three Olympic medals (a U.S. boycott of the 1980 Moscow Games cost him a fourth), setting four world records, running faster at his final Olympic Games in Seoul in 1988 than he did in is gold medal debut in Montreal in 1976 — he has seen his stature grow even more in the 3-½ decades since he retired from competition.

He has become a globe-trotting Good Samaritan who has been heavily involved in ridding sports of drug-aided athletes — he’s still the chair emeritus of the United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) and was the former education chair of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) — and he’s become a leader in a respected global organization that uses sports as a tool for positive social change.

He’s the chairman of Laureus Sport for Good Foundation, the independent charity that, among other things, has been involved in hundreds of projects across the world, including homelessness and street violence in the United States, injuries from wartime land mines in Cambodia, discrimination in Germany, the orphan crisis in Peru, AIDS awareness in South Africa, providing food, medicine and shelter fur Ukrainian mothers and children displaced by the deadly Russian invasion of their country and promoting gender equality initiatives across the world.

The man of the world is back in Dayton this weekend, having travelled here from his home in Atlanta.

Saturday he was at Welcome Stadium — located now on Edwin C. Moses Boulevard — for what is now known as the Dayton Edwin C. Moses Relays.

As he handed out medals to the winners and reminisced, he was followed by a German film crew that is making a documentary on his life.

The project, which was temporarily stalled by the COVID pandemic, is back on the front burner and Moses said the filmmakers have already have been to Atlanta, Los Angeles and various places in Europe, including Norway to talk to Karsten Warholm, the reigning Olympic champ and current world record holder in the 400 meter hurdles.

This weekend the documentarians came to Dayton to capture some of Moses’ past.

He showed them Kimberly Circle, where he grew up on Dayton’s West Side and next to it, Mallory Park on Germantown.

The school buildings were he once went to classes — at Wogaman Elementary and Fairview High — have been torn down, but he planned to visit with some lifelong friends, former Fairview teammates and Bulldogs’ track coach John Maxwell, now in his 80s, who still live here.

While here — at the behest of Dayton Public Schools — Moses also will talk to students at Dunbar and Ponitz high schools and the newly housed Wogaman Middle School on Monday.

“Whether the kids know it or not, they’re getting a real legend,” Victoria Jones, the athletics director of Dayton Public Schools, said Saturday afternoon. “Edwin Moses is the Michael Jordan of track.”

Crutcher stressed he also delivers a great message:

“Edwin Moses has a real story. He was a young man who took his mathematical skills, applied them to track and became a world record holder That’s something young kids can look at and use. They can see how everyday school skills can be used to improve and become the best in the world.”

Family foundation

The foundation of the Moses story goes back to his late parents — Irving and Gladys — and his two brothers, Irving Jr. and Vincent.

His dad was a Tuskegee Airman, a Kentucky State football player and a longtime educator with Dayton Public Sxchools.

Moses once told me how his dad passed on some of his military training to his boys. By the time he was 10, Edwin knew how to iron his shirts, cook breakfast and shine his shoes so they’d pass inspection.

His mom, who was a three-sport athlete at Kentucky State, was a supervisor of instruction with DPS.

Moses said she required the three boys to read 10 books every summer and they did volunteer work for Head Start.

Edwin had a newspaper route, became a top student at Fairview and after his 1973 graduation, he went to Morehouse College in Atlanta on an academic scholarship. He had a 3.85 GPA, graduated with a physics degree, studied engineering and later got a master’s degree in business administration at Pepperdine University.

His mother remained his No. 1 fan. She subscribed to Track and Field News since 1976 and religiously read it cover to cover each month. Over the years she travelled to track meets all around the globe and had her own following at those events.

When she died at 87 in 2016, Moses remembered her “as a superstar.”

Moses’ own path to stardom came after he was deemed too small or slight — he was a 5-foot-8, 135 pound freshman — for Fairview’s varsity football and basketball teams.

Credit: Dayton Daily News Archive

Credit: Dayton Daily News Archive

He did have a knack for track and in college he would grow into the perfect hurdler. At 6-foot-2, he seemed to be half legs with his 37-inch inseam. He had a long, smooth, gliding stride — once measured at nine feet, nine inches — and his book smarts helped make him an unparalleled innovator when it came to technique and training.

When he made his first Olympics in Montreal in 1976, he was initially dismissed as an unproven curiosity.

He may have worn a cut down Afro, dark glasses and a rawhide necklace, but his track resume caught no one’s attention. He was a still a student at Morehouse, which had no track facility of its own and he’d never run a 400 meter hurdles race until just four months before the games began.

Then he went out and not only took gold, but set the world record (47.63). His was the only gold medal won in track and field by an American male athlete in Montreal. While denied a chance to compete in Moscow in 1980 — the U.S. boycotted after Russia’s invasion of Afghanistan — he took gold again in Los Angeles in 1984.

He wrapped up his Olympic career with a bronze medal at the 1988 Games in Seoul, his final competition.

His 122 consecutive victories in the 400 meter hurdles — 107 of them in finals — were the longest unbeaten streak in track history.

ESPN named him one of the Top 50 Greatest Sports Figures of the Twentieth Century.

He was on the covers of magazine’s like Sports Illustrated, Jet and Newsweek. He was on the front of the Wheaties box, was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, was named Sports Illustrated ‘s co-Sportsman of the Year with gymnast Mary Lou Retton and was inducted into the National Track and Field Hall of Fame.

Back here in Dayton in 1984, the city of Dayton took Miami Boulevard and Sunrise Avenue and turned them into the 2.5 mile Edwin C. Moses Boulevard.

Saturday, when Moses showed up at Welcome Stadium at 1 p.m., Aubrey Ways, who was serving as the public address announcer, told the crowd of his arrival.

Soon Moses, who was trailed by the film crew, was surrounded by students who wanted to get their picture taken with him.

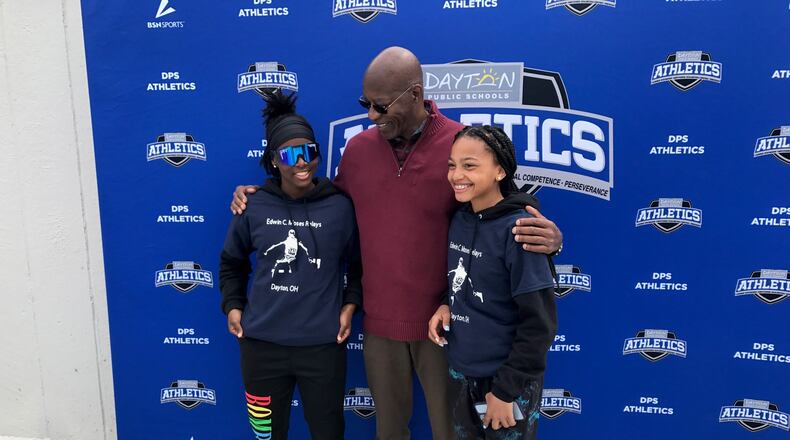

Two of athletes to first approach him were a Dunbar freshman named Jazual Young and her friend Calise Mayberry, a Richard Allen sixth grader. They both wore Edwin C. Moses Relays shirts, the sight of which seemed to pleasantly surprise him.

Seeing that, Calise ran off to get him one.

Important return

After a proclamation was read from Dayton Mayor Jeff Mims proclaiming April 29, Dr. Edwin C. Moses Day in Dayton, the microphone was handed to Moses, whose message was brief but heartfelt.

He told the crowd this was the first place he’d ever seen a track meet and it was where he’d had his first big win — at these very same relays.

“I’m just happy to be here,” he concluded.

He then handed out the medals to the top finishers in both the boys and girls 400-meter hurdle races — Edgewood’s Jacob Crowther and Walnut Hills’ Emma Upp were the winners — and then he took time to chat to several of the athletes.

Coming back this weekend was important Moses told me:

“It’s good for me, but I think it’s good for a lot of people here too, especially young people.

“They see my name on the street sign or the track meet, but they never see the person. I’m like some mythical figure. To physically see me is a big deal. I become somebody real, somebody believable.

“I am somebody who came from the same place they do..

“It shows them dreams are possible here.”

About the Author