Griffith, who's now the principal at Stivers High School and once held the same position at Colonel White, had learned just minutes earlier that his former student – the kid he had mentored, occasionally admonished and always marveled at – had died Tuesday night when the ATV he was driving went through an intersection and hit a minivan in West Dayton.

Martin was just 32.

“He lost his life the same way he lived it,” Griffith said quietly. “Nothing held him back. He was daring and went after life all out.”

A decade and a half ago, Martin – despite being born with no legs – was the most colorful, the most inspirational, the most celebrated, prep athlete in the Miami Valley. And that’s why the news of his death created such a ripple through much of the community Wednesday.

“He was very inspiring and that made him a leader,” said Earl White, who’s now at Belmont High, but was Martin’s football coach at Colonel White and also guided him in wrestling at Roth Middle School.

“Bobby’s attitude was, ‘Yeah, I know I’m disabled, but it’s not holding me back. He’ didn’t ask for anything extra and he wasn’t given anything extra.

“He showed other kids – especially kids in the city who come from disadvantaged situations – that you can do what you want to do if you put your mind to it.”

Martin stood just three feet tall and got around the hallways at Colonel White the same way he navigated the sidewalks and streets of Dayton. He handled a skateboard as well as legends Tony Hawk and Rob Drydek.

»PHOTOS: Remembering Bobby Martin

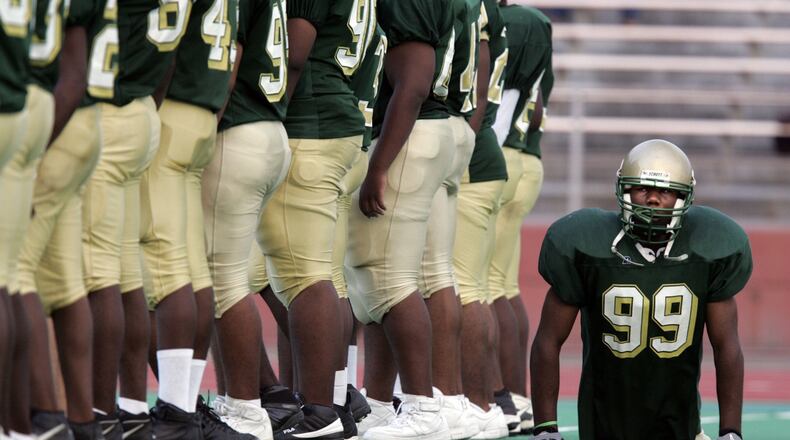

He weighed 110 pounds at Colonel White. His football pants were cut off just a few inches below his belt and on his hands he wore black gloves.

His upper body was especially powerful – he could bench 220 pounds – because when he ran he used his arms as his legs. Wearing No. 99, he was a special teams player for the Cougars and was the backup nose tackle.

Most folks were amazed by what he did on the field. When Colonel White travelled to Valley View for a game, the Spartans crowd gave Martin a standing ovation at game’s end and then-coach Jay Niswonger was so inspired he sent out videos clips of Martin to many people he knew,

But four weeks into the season – in a game at Mt. Healthy in Cincinnati – a referee crew pulled the plug on Martin’s wondrous efforts.

Martin got into the game for just one play before halftime and during the break, the head official told White that Bobby could no longer play because he was not wearing the mandatory equipment. He had no shoes, no knees pads, no thigh pads.

Never mind he had no feet, knees or thighs.

Colonel White coaches pleaded to no avail for common sense. That’s when Martin tied a pair of shoes to his belt in order to try to meet the mandate. But school officials nixed that as degrading, so Martin’s night was done and he was in tears.

I talked to him the following Monday at practice.

“It’s the first time in my life I ever felt like that,” he said. “Everybody was looking at me, telling me what I didn’t have. I felt like a clown. I hated it.”

The Ohio High School Athletic Association stepped in a few days later and overruled the ref who said he was afraid Martin – who had passed his physical, had the consent of his mom and already had played in the first three games – might get hurt.

To compound the snub, a Cincinnati sports radio host ripped Martin and Colonel White, calling the whole venture “a freak show.”

That drew rebuke from this column to Sports Illustrated.

By the time the season ended, Martin had made 41 tackles, registered three quarterback sacks, recovered a fumble and before the final game was named Colonel White’s Homecoming King.

The honors kept coming after that. The Cincinnati Bengals made him a guest on their sideline at a game, as did the Oakland Raiders and Green Bay Packers when they came into Paul Brown Stadium.

The Browns brought him to a Saturday practice in Cleveland and then had him on the sidelines for a game against the Kansas City Chiefs. He gave in-game pep talks, the Browns rallied from 14 down in the fourth quarter and won in overtime and then Martin and Jim Brown gave a post-game talk in the dressing room.

“We gotta have B back for our next game, he’s our good luck harm” said Braylon Edwards.

In private the receiver said there was more to it than that:

“When you see B, it lets you know nothing you’re going through is that bad. You see him enjoying life and you think, ‘I better damned sure believe I gotta blessed life!’”

Martin was also a guest on “Live with Regis and Kelly” and he appeared on stage at the Apollo Theater in Harlem for the BET Awards. Boise State flew him out for an award and he went to California to be on The Best Damned Sports Show Period.

He returned to Los Angeles, where he won an ESPY in 2006 as the Best Male Athlete with a Disability and hobnobbed with Serena Williams, Kobe Bryant, Shaquille O’Neal, Ludacris, Matthew McConaughey and Kiefer Sutherland.

Reporters from Spain, Italy, Korea, China and England came to Dayton to write about him. A photo of him with his Colonel White teammates was named one of the 100 top photos ever to appear in Sports Illustrated and a Canadian toy company made an action figure of him.

And that image fit, especially after a November 2001 fire at the family home on Lexington Avenue. After escaping, Martin remembered his pit bull, Pebbles, and her puppies were still in an upstairs bedroom.

As neighbors pleaded with him to stay outside, he went in through the smoke and fire and managed to rescue Pebbles and all her puppies.

“It was foggy and black and I could feel the heat, but I had to save them,” he explained to me later.

‘He always founds ways to get around’

He was born with caudal regression syndrome and his body stopped at his pelvis.

Early on his father – who soon drafted away from his life but later returned somewhat – nicknamed him Boo Hoo because he cried a lot as a baby

That was understandable. Bobby needed several corrective surgeries, had to be taught by an occupational therapist how to roll over and he was asthmatic.

His mother, Gloria, was steadfast in her support and once told me: “All I ever wanted for Bobby was for him to be the best man he can be.”

And he especially was once he learned to get around on a skateboard.

“He could work miracles on that skateboard,” White said. “He always found a way to get around.”

He even drove, though that often became a frightening prospect for passengers and one that eventually got him a series of tickets for speeding, no license and failure to comply.

He didn’t have hand controls in his car early on, so he held the steering wheel with one hand and used the shaft of a golf club to push down the gas pedal and the brake.

First big win

I was there the day of his first big sports triumph.

He was an eighth grader, wrestling at 92 pounds for Roth. He had lost his first six matches of the year and that day was pitted against Stivers’ George Parks, who had him trapped on his side and was about to flip him on his back for the pin.

Parks had already pinned him earlier in the season.

Martin’s teammates cheered for him to fight back, as did White. In the stands, so did Bobby’s mom and his grandmother, who held her cane.

And then, just like a sports action figure, Martin got a second wind, wiggled free and eventually outmaneuvered Parks for the 14-11 victory.

While Parks was crushed, he held Martin’s arm up in victory and later explained: “It’s kind of strange. I was upset, but I feel real happy he finally won.”

The Stivers coach told his team: “Today you boys saw true courage. Bobby Martin is all heart.”

When he won, Martin bounded up into the bleachers to his grandmother and mom, then came flying back down so he could join his teammates for a victory ride home.

As he went barreling past, White said: “Bobby, slow down. No running.”

That day the coach gave no thought to what he had just said.

Wednesday he gave it plenty thought:

“This is sad….just real, real sad.”

About the Author