Branch, who also trains with Gregory and works out regularly in West Chester, hooked his wheelchair to a platform using a winch strap and then began to put on his fencing gear.

Before he added his glove and mask and reached for his weapon, he sat down and took off his right prosthetic leg — with its tennis shoe and black sock still attached — and lay it at the base of his chair.

Finally, one by one, the three able-bodied OSU fencers sat in the chair opposite him and began their up-close sparring sessions.

Although Branch, who’ll soon be 39, was nearly twice the age of all of them, he had the advantage, and afterward each Buckeye sang his praises.

“He’s very fast,” said Claire Galavotti, a 19-year-old junior from Chicago.

“Yes, he’s good,” admitted Lorenzo Mion, a 19-year-old sophomore from Sao Paolo, Brazil. “He scored a lot more touches than I did.”

“He kicked my butt,” grinned 20-year-old Anna Heiser, an NYU transfer from Canton. When told Branch’s age, she shook her head: “Age has nothing to do with it. He’s very, very good…He is something.”

Branch is something all right and the three young Bucks don’t know the half of it.

A talented wheelchair fencer — he’s competed all around the world the past few years and as of now is qualified to represent the United States at the 2024 Paralympic Games in Paris — he has a resume just as impressive as a police officer.

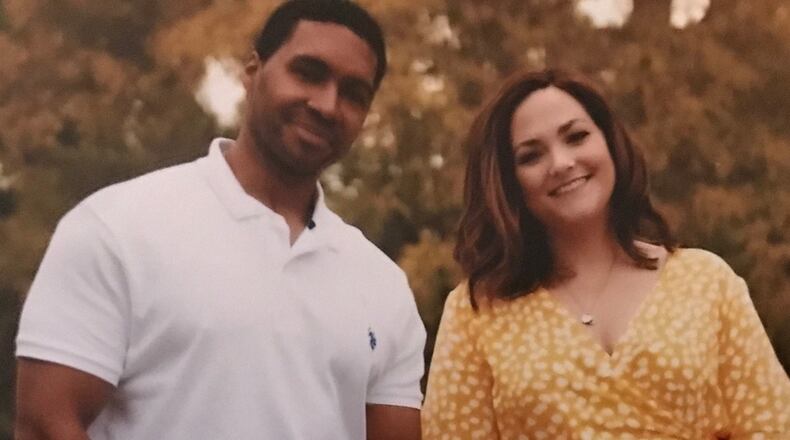

In 2018 he was named Dayton’s Police Officer of the Year and he and his wife Brittany — they have two young daughters of their own — have been lauded for buying Christmas gifts for underprivileged children in the city.

Two years ago, he won the department’s prestigious Steve Whalen Memorial Policing Award for his work in the community, especially for mentoring youth and building relationships in group homes.

And he’s thought to be the only active police officer in the state of Ohio with one leg.

A return to fencing

From the time he motioned to the Michigan semi driver, who’d gotten out of his damaged truck on the ice-coated, northbound stretch of I-75 near US-35 just before midnight on December 16, 2016, to come to the passenger side of his patrol car so they’d be “safe” to the time he awoke in Miami Valley Hospital after the first of his four surgeries, everything is a blur to Branch.

“I don’t remember any of it,” he said quietly. “So everything else I tell you has been relayed to me.”

He doesn’t remember an SUV spinning out of control and hitting his patrol car as he spoke to the semi driver, whose rig had tangled with another car just before that.

He doesn’t remember getting pinned by the impact and crumpling to the pavement, severely injured and bleeding excessively from an open wound to his destroyed right leg.

He also had a head wound, broken ribs. a ruptured spleen and four of his front teeth were knocked out.

He was drifting in and out of consciousness and in danger of bleeding to death until some of his fellow officers arrived and a tourniquet — applied by fellow rookie officer Bryan Camden — was fastened to his leg.

That kept him alive and enabled the rescue squad, once it arrived, to transport him to the hospital just before I-75 through downtown Dayton was shut down because of numerous, multi-car wrecks.

He said he doesn’t remember Brittany, the girl he first met at a Halloween party nearly a decade earlier, being at his side in the hospital — she was there 12 days straight — and how she endured the news when informed his right leg had been amputated in a difficult “life over limb” decision, as trauma surgeon Dr. A. Peter Ekeh described it.

And he doesn’t remember being told how police officers kept a vigil at Miami Valley throughout his stay.

One thing he did remember the other day was how, when he finally woke up and looked down at the stump of his right leg — ensuing surgeries would result in an above-the-knee amputation — he had a profane response.

At the time he didn’t know his front teeth were missing, so he said his emotional outburst came with a cartoonish coating:

“I’m not going to curse now, but back then I said, ‘How the f--- am I going to fence now?’ Without my teeth it came out a little funny.”

He sounded like Elmer Fudd, the Looney Tunes nemesis of Bugs Bunny.

Although he’d been a police officer just eight months when he was injured, he’d been a fencer for nearly a decade and a half.

He’d been introduced to the sport in gym class at Northmont High School and by the time he graduated in 2003 he was one of the top prep fencers in the state.

When he went to Wright State — where he got an undergrad degree in international studies with an emphasis on Eastern European politics and the Cold War and then went to graduate school to study international comparative politics — he taught fencing at the school.

By 2010 he had an A rating.

Then, in a sport that depends heavily on footwork, he suddenly found himself missing much of his right leg.

After initially refusing other people’s suggestions to try wheelchair fencing, he was recruited to represent the U.S. and given some sponsorship money and a chair to compete in.

Although he’d only fenced twice from a wheelchair, he entered the 2018 International Wheelchair Amputee Sports Federation’s Americas Championships in Saskatoon, Canada, and won gold in the Category A men’s foil.

He would win the next tournament — this one held in Brazil — and soon was competing around the world.

“In 2019 I competed in 10 countries,” he said.,

Now he has accumulated enough points to qualify for the Paris Games. If his closest competitor in points should surpass him after competing in Poland early next month, Branch will head to Brazil later in July to hopefully reclaim his lead.

Another concern before Paris though is finances, especially since he no longer has a prominent sponsor.

“It cost $30,000 to compete in 2019,” he said.

Cousins Ethan Reigelsperger and Tiffany White started a GoFundMe page to help with his costs so he can train and travel.

In her plea, White wrote: “If anyone deserves support and the opportunity to continue this journey to see how far he can go competing worldwide, it’s Byron. Byron is inspiring in his professional life as well as in his fencing career. He will continue to pay it forward, and he will continue to show others what they, too, can overcome. Please consider giving Byron your help by supporting his quest to get to the Paralympics!”

For more info on Branch’s Olympic quest, visit his Facebook page.

‘He is something’

Before he left his Bellbrook home for Ohio State the other day, Byron talked about what he and his family have been through the past few years.

When her husband admitted he was hazy on the immediate aftermath of his injury, Brittany — who was at the kitchen table with seven-year-old Chloe and five-year-old Peyton — brought out a gray-covered photo album, which Byron promptly handed to me.

“I’ve never opened this thing,” he said quietly.

“I’ve had no need to. I am that person.”

Inside, I found photos showing his battered face as he lay in his hospital bed. There were pictures of him with his missing front teeth, of him getting his prosthetic leg and him relearning to walk.

Those visuals aren’t as haunting to Brittany as was the first thought she had after the accident,

Police had come to her door after midnight and told her she needed to come with them to the hospital. At the time, Chloe was eight months old and suddenly Brittany felt as if she were freefalling.

“For the first three hours, I thought Byron was dead,” she said softly.

“Finally, they came out and told me he was alive, but they had to amputate his leg, I was relieved. I said, ‘OK, we’ll be fine.”

She now admits that was easier said than done, even though they both had the best intentions.

Byron was determined to return to work as soon as he could and pushed himself through rehab.

“I’d been going to the gym six days a week, but when I first got back after the accident, I found out real quick the toll that had been taken on my body,” he said. “I was able to do just five pullups and it felt like I ran three miles. I lay on the ground and thought, ‘Oh my God, this is miserable.’”

He said he lost 43 pounds in the hospital, but was quick to point out: “They said my amputated leg probably weighed 15 or 20 of those pounds.”

He said he had a “fantastic” physical therapist who had him walk all the steps at the Dayton Art Institute and at Sinclair: “She took me to a construction site, too, and had me walk all around it to get used to different terrains, and she took me to that tall building on McFadden (Ave.) where the firefighters train and had me walk those steps. She really pushed me.”

He returned to light duty within seven months of his injury and was back patrolling East Dayton 364 days after he’d been hurt.

Now he also trains new officers.

Behind the scenes though, it was tough Brittany said:

“Initially everything was OK, but once the adrenaline wore off, I had some PTSD. There were a lot of things to work on. Our second daughter had arrived and there was a lot of stress.

“And a year or so after his accident, Byron found himself getting angry. He was still grieving his loss. That second year was tough for both of us and took a lot of therapy and family support.”

Through it all, Brittany – who grew up in Bellbrook and graduated from Wright State – remembered what initially had attracted her to Byron, who is three years older:

“After the accident somebody put it perfectly. He told me, ‘Being around Byron feels like the sun came out.’ And that’s what I felt, too.”

As things have gotten better, Byron has said he’ll try to represent the U.S. in Paris and then retire from competitive fencing. He’s already taught some young people the sport and helped one girl get a scholarship.

Brittany thinks he would be an excellent fencing teacher and he’s also hoping to become a competitive shooter.

But while it may seem like they’d left all the worst from that 2016 accident in their rearview mirror, Byron got a jarring reminder in 2019 that something else was behind him.

“Actually, I’ve been hit on the highway twice,” he said with a weary laugh. “People only know about the first one. But I got hit three years after that, too.

“It was the same thing. I was out on the highway and the weather was horrible. Some girl wrecked her car where Route 4 turns into 75 going south. It was right at the bottom of that huge overpass that turns down. It’s a blind curve coming around it and down.

“She’d wrecked her Jeep, nothing major, and I when pulled up. I said, ‘OK, I’ve got some experience in this. Let’s get in my car to talk.’

“She was in the backseat, I’m up front, and I asked her name and she told me. As I started to ask for her address, I got the question partially out when a car going 60 miles an hour smashed into the back of my car.

“The back window was smashed into my back seat. My shotgun was knocked out of the rack and the computers were knocked off. So were the cameras on the windshield. It was super dusty in the car and I was coughing, but we were both OK.

“The girl who hit us, her head was bleeding from hitting the front window. She was 16 and had just gotten her license. She was terrified. She’d never driven in bad weather before and when she came around the curve and saw me, she freaked and slammed on the brakes and flew into us.

“The first thing that went through my mind was, ‘How am I going to get on the radio and say ‘I just got hit by a car!’ and not have everybody lose their minds?

“I’ve had people ask if I get worried out there now, but you can’t do this job scared and I never have been. But you never really know what you’re made of until something happens and you’re put to the test.

“As for me, I’m just happy to have my family and do what I’m doing. ... I’m just happy to be alive.”

The OSU fencer put the tip of her foil right on it:

“He is something.”

About the Author