“And he was right. I fell in love with Indy the very first time I experienced it.”

Over 200,000 people were there that warm and sunny day — May 30, 1952 — as Troy Ruttman, driving a dirt car owned by J.C. Agajanian, became the youngest winner of the Indianapolis 500. He was just 22 and he took the lead when Bill Vukovich, who’d led for 150 laps, had the steering linkage break when he was just nine laps away from the checkered flag.

“Everything about the place was so exciting,” Gyenes remembered. “It was more than I ever dreamed it would be, so I kept going back and going back and going back.”

Gyenes is 82 now and has not missed a race since that very first time he walked into the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

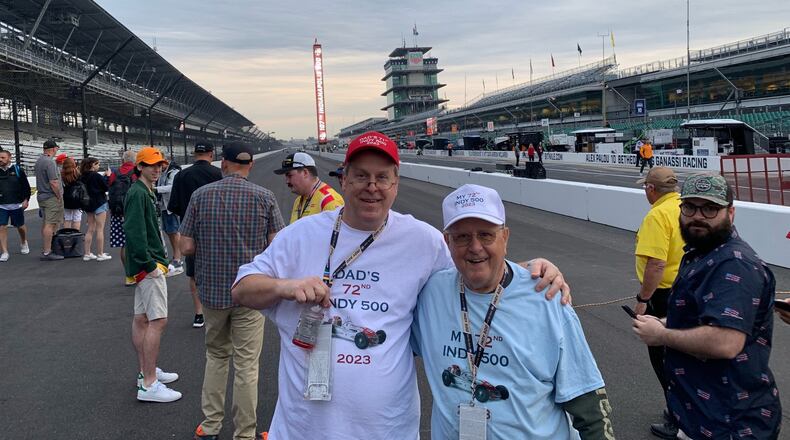

Today, he’ll be attending his 72nd Indy 500.

Like usual, he’ll be accompanied by his son Greg, a Miamisburg High School Hall of Fame basketball player who just finished his 34th year teaching history at the school.

Although he’s not as immersed as is his dad in all things related to the race — and he’s had his own string broken on occasion so he doesn’t keep close tabs on the exact number he’s attended — Greg guessed this will be his 35th Indy 500.

Father and son Gyenes will be wearing T-shirts and matching caps that celebrate Ed’s Ironman feat.

Ed’s shirt reads: “My 72nd Indy 500 in 2023.”

Greg’s says: “My dad’s 72nd Indy 500.”

The pronouncements will draw people to them all day who want to take a photo, shake Ed’s hand or just talk racing.

But even without the T-shirt testimonials, Ed is something of a celebrity at the 500.

A few years ago on race day, Ed and Greg were sitting on the aisle, close to the track in Turn One, when midway through the 500, IMS president Doug Boles suddenly appeared on the stairs in front of them.

“I figured he was going to see the TV people up above us, but, ‘No!’ He came right to me, poked me in the chest and said, ‘Ed, I just want to come and congratulate you for all the years you’ve been coming to the Indianapolis 500.’ He’d seen my shirt somewhere and came and found me. "

Some years before that, Roger Penske – who took over ownership of the track in January of 2020 and whose teams have won the race 18 times – sought Ed out at an Indianapolis hotel in the days before the 500.

And today, as has become tradition in recent years, Robbie Fast, the spotter for veteran driver Scott Dixon – the six-time IndyCar Series driving champ, who won the 500 in 2008 and has led the race a record 665 laps in his career – will come up into the stands before the race and sit and talk with Ed.

The two visited last week, as well, when Ed spent five days at the track watching time trials and practice. In the past, Fast has taken him through Dixon’s big race transport, as well.

“Except for his family, the Indy 500 means more than anything else to my dad,” Greg said.

Ed agreed: “When February hits, I start getting excited and count the days until I can go to the time trials…and then the race.

“It’s like waiting for Christmas as a kid.

“I’m 1,000 percent passionate about all this. It’s the biggest sporting event in the world. A few years ago they had something like 400,000 people. To put it in perspective, that’s four times the crowd that goes to an Ohio State football game.

“There’s nothing I’ve ever been to that matches it.”

And this isn’t just grandiose assessment from a guy who’s never been beyond the Brickyard grandstands.

An All-State baseball player at Fairmont High School, he got a scholarship to Ohio State and then, by his mid-20s, he was a big-time college basketball referee in the Big Ten, the Mid-American Conference and the Ohio Valley.

Although he’d prematurely retire as a ref to concentrate on the demands of his job and family, he did officiate some NCAA Tournaments, including the 1971 NCAA West Regional in Salt Lake City. That’s where he shared the court with John Wooden, whose UCLA Bruins would go on to finish 29-1 and win the national title.

“I’ve been to Super Bowls and World Series and other top events, but nothing tops Indy,” Ed said.

Each year when he comes for the time trials, he said he spends part of one day walking the whole inside of the 2 ½ mile track.

Today —race day — he and Greg have a set routine.

Ed lives in Mansfield now – he and his late wife, Doris, moved there because of his job in 1994 – and he drove to Greg’s place in Miamisburg on Saturday.

In the evening they went to the Sorg Opera House in Middletown and saw a theatrical production of “James and The Giant Peach.” In the past there have been trips to the Cincinnati Zoo, the Cincinnati Reds and Dayton Dragons games.

This morning they planned to be on the road by 5 a.m.

“I don’t remember a trip where Dad hasn’t started singing ‘Back Home Again in Indiana,’” Greg laughed.

He said when they get close to Indianapolis, his dad’s adrenaline is pumping and he has to chide him about his driving:

“I tell him to slow down. It’s like he thinks they’re going to start without him.

“We’re usually one of the first people at the track, but by about 10 it really gets fun to watch Dad. You get the Parade of Bands, the 500 introductions, the flyover and, for all those years, Jim Nabors was overwhelming.”

This year Ed will watch for two of his favorite drivers: Dixon, who is starting on the outside of Row 2 and Tony Kanaan, the popular driver who won the race in 2013 and has said this will be his last Indy 500. He’ll start on the outside of Row 3.

Over the years Ed had other favorite drivers, including Vukovich and Eddie Sachs, both of whom died in terrible crashes during the Indy 500.

Vukovich had won in 1953 and 1954 and was leading again in 1955 when his car got caught in a chain reaction crash, went airborne, flew out of the track, hit a low bridge and burst into flames.

Sachs, known as the Clown Prince of Racing, had won the pole in 1961, as he had the year before, and was leading with three laps to go when he chose to pit and replace a tire that was delaminating. That allowed A.J. Foyt to win.

“I’d sooner finish second than be dead,” Sachs said after the race.

Three years later — on the second lap of the 1964 Indy 500 — he was killed in a fiery crash that involved seven cars. The carnage also would claim driver Dave MacDonald, who died two hours later at Methodist Hospital.

“That’s my one worry, I don’t want to see anyone get seriously injured or killed,” Ed said quietly.

He said he just wants to see good, safe racing and he said you can appreciate that all the more when you’re at the track and can take in the spectacle, rather than just watch on TV:

“You get the chills. Talk about speed and power! When those 33 cars get the green flag and they go into Turn One all bunched up at over 200 mph, it’s a living tornado!”

‘We had everything but a car’

As a senior second baseman at Fairmont, Ed Gyenes (pronounced Jen-us) was voted to the first team All-Southwest District. Second-team honors went to a Western Hills second baseman.

His name?

Pete Rose.

Although he went to Ohio State, Ed said he soon was forced to come home:

“My junior year in high school, my mom had suffered a serious stroke. She was bedridden and couldn’t walk or talk. My dad ran the printing press at NCR and was under a lot of pressure. During the winter of my freshman year at Ohio State, he had a severe nervous breakdown and I had to go take care of them.”

He got a job at Dayton Steel and ended up meeting and falling in love with Doris Smith, a Miamisburg High grad, who worked there.

They were married in 1960 and when she passed away in October of 2020, they were four days shy of their 60th anniversary.

Their two children — Catherine and Greg — both have splashy accomplishments on their early resumes.

“Catherine was just an outstanding dancer,” Ed said. “She was Miss Cincinnati and Miss Dance of Ohio. And the Miss Ohio title (in 1984) came down to her and Melissa Bradley and Melissa won.

“And Greg was just an outstanding basketball player. He played hard and in the last regular season game of his senior season, he scored 50 points against Edgewood.”

Greg went on to play at Muskingum College and Ed said he made all but one of his games, even though his job – with Beckley Cardy -- had taken Doris and him to Duluth, Minnesota.

And Ed didn’t just keep his Indy streak intact up there, he further immersed himself in the aura of the race.

“Up in Duluth, it was like 25 degrees below zero and some of us started talking about going to the Indy time trials,” he said. “We formed a race team: Team Rameri. It was the only simulated race team in Indianapolis 500 history.”

“Rameri stands for Ragamuffin Engineering Racing, Inc,” he laughed. “We ended up with over 50 people on our team. They were venders and my partners who worked with me in Duluth, especially Jim Ingledue. He had been a tremendous athlete at Springfield High and Wittenberg. He really promoted the team. He was our ‘driver.’ We called him Fernando Poppi.

“People thought we were a real race team. We had hats and shirts and pins and people would come up for autographs.

“We had everything but a car.

“One time we were staying at the Hampton (Inn) and when we checked in, they had a big banner in the lobby that said: ‘Welcome Team Rameri.’

“After a while, in walked Roger Penske. He asked for a room on the first floor and they said, ‘Sorry Mr. Penske. Team Rameri has the whole first floor.’

“He said, ‘Who in the world is Team Rameri?’

“When he came over to talk, he noticed our shirts and all, he said:

“‘You guys are dressed better than us!’”

Unforgettable ride

“This has been a fun father-and-son thing we’ve done for quite a long time,” Greg said of their annual Indy 500 trips.

“The most enjoyment I get from it is watching my dad get such enjoyment. And since my mom passed away, this is the main thing that keeps him going.”

Some years ago, before Doris died, she and Greg and some of Ed’s coworkers and friends all chipped in and surprised him with a two-lap driving experience around the Speedway.

In a black fire suit and helmet, he joined an IndyCar driver who’d been bumped from the race and rode in a two-seater car at speeds close to 200 mph.

“You could feel the power, but it was smooth,” Ed said. “But when we got in the turns, that’s when the Gs wanted to pull you out. The force you felt was amazing. It’s an experience I’ll never forget.”

“He looked like a little boy in a candy store,” Greg said. “He was beyond overwhelmed.”

“It was the biggest thrill I’ve ever had in my life,” Ed said. “I’ve had so many beautiful experiences at the speedway over the years — that’s why I keep coming back.”

Greg said his dad hasn’t missed an Indy 500 since his first race in 1952.

“His body won’t allow him to be sick – not in May,” he laughed.

Several years ago, one of the IMS track ambassadors saw Ed and his buddies in their Team Rameri regalia. “He got so curious, he came up and said. ‘Just who in the hell are you guys?’” Ed laughed.

When they explained, he said he wanted to join their team and then he gave them a real treat. He took them into the basement of the IMS Museum, a place off limits to the public.

“They had rebuilt Eddie Sachs’ car and it was down there,” Ed said. “He let me sit in it. That just got my heart.

“That year, Jay Leno was at the track too and he was trying to get down there, but they wouldn’t let him.”

Leno found out celebrity only takes you so far at Indy.

When it comes to the 500, Ed Gyenes has the weightier currency:

He has longevity.

And today nobody will have to ask who in the hell he is.

They can just read the front of his shirt:

“My 72nd Indy 500 in 2023.”

About the Author