“I’m sorry,” he said softly. “I’m sorry.”

His sentiment hadn’t come from a nostalgic revisit to his days as an undersized center for the Dayton Flyers in the late 1950s and early 1960s, even though he’d had big games against rivals like Louisville and Xavier, had been on the team that made it to the NIT Final Four, has continued his friendship with some of his old teammates and now remembers his late coach, the oft, hard-bitten Tom Blackburn, with more affection than some other old Flyers:

“I loved Tom Blackburn. He gave me an opportunity.”

Allen also hadn’t become emotional because he was reflecting on his 58 years as a trial lawyer. That has included early years handling criminal cases in Lima and, for most of the rest of his career, litigating civil cases for E S Gallon in Dayton and, the past 27 years, working for Casper & Casper in Middletown, where his specialty has been helping injured workers.

The other day Allen was moved to tears as he talked about his volunteer work with the Veterans History Project of the Library of Congress.

It’s an oral history effort that collects and preserves firsthand remembrances of United States’ wartime veterans. In Allen’s case, that’s meant gathering stories from veterans of World War II, Korea and Vietnam.

“I just love these guys,” he said in a half-whispered aside to himself. “And if we don’t preserve their stories now, it won’t be long and they’ll be lost forever.”

Thanks to his efforts, veterans have shared some of their most personal wartime memories, often ones even their own families have not heard before.

There was the Vietnam vet who told of his unit being ambushed and how he carried his dead comrade up a hill.

And there was the vet who told of returning from Vietnam with a fellow soldier and being spit on by four guys in Cincinnati.

Another videotaped story was about a Vietnam combat nurse, who followed her boyfriend into war, married him and ended up working in an intensive care ward caring for injured soldiers just off the battlefield.

Just a few days ago I accompanied Allen and his cameraman — Jim O’Donnell, a long time Covington attorney who’s a Navy veteran — to the Sidney home of Mark Deam, who’d received a Purple Heart, a Bronze star with a ‘V’ device and a CIB (Combat Infantryman Badge) after a challenging tour in Vietnam where casualties reduced his 120-man platoon to just 35.

One of his favorite veterans, Allen said, was the late Harold Brown, a celebrated Tuskegee Airman who flew 30 missions in his P-51C during World War II before his plane was hit by the shrapnel of an exploding German cargo train he’d strafed in Austria.

“Eventually he had to bail out and the citizens who captured him there wanted to hang him until a local constabulary saved him and handed him over to the Germans,” Allen said. “They put him in a POW camp for airmen.

“It was toward the end of the war and the guards were Luftwaffe pilots who didn’t have any planes to fly anymore. He said, pilot to pilot, they got along great in camp and when Red Cross items came in, the Germans were so hungry, they took part and gave the rest to the prisoners.”

Allen met Brown at the Champaign County Aviation Museum and eventually went to his home in Port Clinton for an engrossing interview.

Growing up in Minneapolis, Brown had a fascination with flying and saved $35 to take flying lessons. But at $7 a lesson, he ran out of money before the course was complete.

Although he hoped to join the Tuskegee Institute flight program, he was so small, he didn’t meet the 128 3/4 pounds weight minimum, so he set out to fatten himself up.

After the war, Brown went to Ohio State University, got a doctorate’s degree and ended up as a vice president of Columbus State Community College. He died last January at age 99.

“When I interviewed him, he was still sharp as a tack,” Allen said “What a wonderful guy. Just wonderful.”

Brown is one of some 80 veterans in seven states that Allen has interviewed in the six years he’s been involved in the Library of Congress project.

“I wish I’d gotten involved in this 15 years ago,” Allen said. “So many of the stories have been lost.”

He conducts the sessions with the help of a camera person. The other day it was O’Donnell. Other times, for interviews south of Dayton, it’s often Tom Lee. And especially for those out of state, Mary, his wife of 62 years, handles the camera.

The interviews often take 90 minutes to two hours.

Allen does research beforehand, and he said his experience as a trial lawyer for more than 50 years makes it easy to ask questions and follow ups.

He takes the interviews to the Cincinnati-Hamilton County Library, where they are put in DVD form. The original is sent to the Library of Congress and the veteran’s family then gets as many free copies as it would like.

He said some veterans have said they couldn’t watch the DVDs once they got them back. They had revealed stories they’d never articulated before and didn’t want to relive them again.

“A lot of Vietnam guys are hard to get,” Allen said. “They don’t want to agree to do an interview. Many resent how they were treated when they got back. They don’t want to tell that story.

“I interviewed one guy who told me how he and his buddy came back and were going through the Cincinnati Terminal. They had their uniforms on, and they were accosted by four guys. Officers had told them, no matter what someone says or does, just keep right on going. But…”

Allens emotions were beginning to well up again.

“These guys were spit on,” he said quietly, his voice shaking.

“The guys said they wiped the floor with those four in nothing flat, but it was heartbreaking to be treated like that.”

As he finished the story, tears spilled from his eyes, and he apologized again.

On the court

Allen went to St. Aloysius Academy in New Lexington, a small town in Perry County, 20 miles southwest of Zanesville.

“I tell people I’m the proud graduate of a girls’ boarding school,” he said with a grin. “And it was.

“The Franciscan nuns started the school in the 1800s and in the 1900s they started a boys military academy for grades one through eight. In the 1940s the bishop convinced the school to let (high school) boys attend during the day.

“My wife was a boarding student there. She’d come from St. Albans, West Virginia.”

Allen’s older brother Mike, who was 6-foot-9, first attended St. Aloysius. He won All-Ohio honors and led the team to the 1954 Class B state title. He went on to Ohio State for two years and then, much like Bill Uhl had done, ended up transferring to Dayton.

Although Pat scored as many points as his brother had in high school, he wasn’t as tall, and his team didn’t have the same kind of success as the 1954 squad had.

“I ended up with just two scholarship offers,” he said. “One was to Steubenville College and the other was to the University of Dayton.”

Freshmen weren’t eligible for varsity then, and Allen said he didn’t play a lot on the Flyers’ freshman team. He flirted with the idea of transferring to Ohio University, but then he became a starter on varsity as a sophomore. That was the one season he played alongside Mike, who was a senior.

Allen said he liked playing in the UD Fieldhouse:

“They called it ‘Thrombosis Fieldhouse.’”

His sophomore year the Flyers went 14-12 and Allen averaged 3.4 points and 4 rebounds a game. He doubled his scoring output the next season and the Flyers went 21-7 and made the NIT quarterfinals.

As a senior, Allen averaged 8.6 points and 8 rebounds a game and the Flyers made the 1961 NIT Final Four before losing to Holy Cross.

The following year, with Allen graduated, UD went 24-6 and won the NIT.

“They needed to get rid of me to win the NIT,” he said with a laugh.

After UD, he ended up going to law school at Ohio Northern University and then became a junior partner at the Lima law firm of Navarre, Rizor, DaPore and Allen. He was there seven years and did criminal trials. At the time he also played industrial league basketball. His Bluffton Boehrs team won the state recreation title.

Moving to Dayton, he worked 25 years for the E S Gallon law firm, while continuing to play recreation basketball until he was 38. Since then, he’s had two hip replacement surgeries, a knee replacement and he said his shoulder is “shot.”

“Too many hook shots,” he grinned.

He joined Casper & Casper in 1997. He and Mary have four children and they now live on a 106-acre farm between Lebanon and Waynesville.

The 84-year old Allen continues to practice law on a limited basis. He’s a regular at UD games, sitting in the 200 level above the players’ tunnel. He often gets together with some of his former teammates, especially Hank Josefczyk and Frank Case.

But one of his most cherished pursuits now is the oral history project with veterans.

Helping veterans

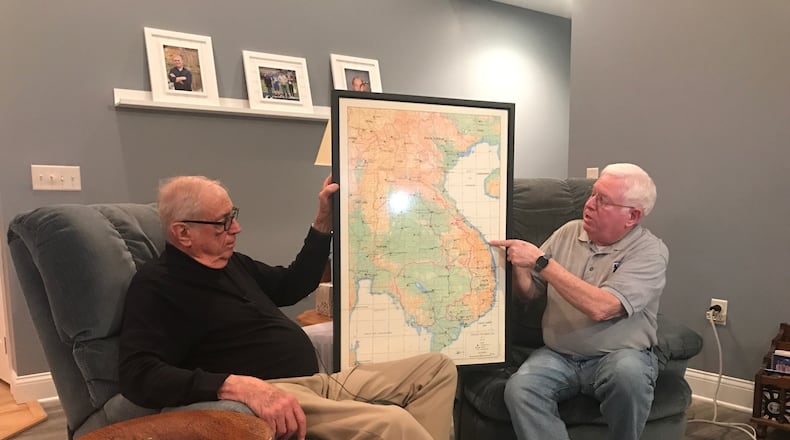

He and O’Connell and went to the home of Mark and Joyce Deam on the north side of Sidney the other afternoon and set up their camera in the living room.

They brought along a map of Vietnam mounted on a board and it would serve as a visual aid so Deam could point out Chu Lai — southwest of Da Nang — where he was stationed.

Allen learned of Deam through a veterans’ group in Troy. Although not a vet himself, he’s been embraced by many area veterans’ groups who recognize his passion and appreciate his heartfelt work. He attends their weekly or monthly gatherings and often gets tips on other soldiers with stories.

A 1966 graduate of Sidney High School who’d been a snare drummer in the schools All-Boy Band, Deam was drafted in August of 1967.

Four months later he slipped home on a short leave from Fort Lewis in Washington and married Joyce (Eipper), whose locker had been next to his in high school.

Seven weeks after that he left for Vietnam. where he was assigned to Company C, 1st Battalion, 6th Infantry, 198th Light Infantry Brigade.

Soon after getting there, a superior made him a radio operator.

Three months after getting to Vietnam, Deam was wounded in the right knee by shrapnel during the Battle of Hill 352 in Quang Tun Province.

North Vietnamese Army regulars were well-entrenched there and Deam said, even though he’d watched the hill be bombarded by US jets for an entire day, NVA soldiers managed to survive in spider holes and popped out as they approached.

Deam returned to duty and though he didn’t go into detail about the deadly consequences of his tour, he did note over 70 percent of his platoon had not survived.

“The average John Doe has no idea what these guys went through and a lot of them don’t share it once they get home,” Allen said.

Not only does he not want their stories to be forgotten, but sometimes he sees how participation in the project can help a veteran in other ways.

He recounted meeting former combat nurse, Nancy Orth of Fairfield, who he said had followed her fiancé to Vietnam and married him.

“When she got off the plane, her first assignment was a combat hospital right near the front lines and her first patient was a triple (amputee) just in from the field,” Allen said. “She couldn’t handle it, so they assigned her to an intensive care ward, and she loved it.

“And when she got out of the service she worked in intensive care units in hospitals around Cincinnati.

“She’s disabled and uses a walker and during our interview she told me she had a 50 percent disability rating,” Allen said. “As I talked to her, I thought, ‘This lady needs more help than this!’

“She’d been told she couldn’t get more than 50 percent, but I tied her in with the Veteran Social Command, a group that gets together every Thursday in Trenton. I go there every week and they’ve kind of adopted me as family. They help veterans with benefits, and, within three months, they were able to get Nancy 100 percent disability.

“She’s been grateful ever since and, every once in a while, we have dinner. She’s so appreciative, but it’s the least we could do after she did so much.”

As he was telling the story, his eyes welled-up again.

About the Author