“You’re dying right now.”

As sick as he was, Dr. Paul Colavincenzo, a Kettering anesthesiologist and Navy war veteran, remembers that somber nighttime conversation in April of 2016. He had been in Kettering Medical Center for eight days and his condition had deteriorated.

“I came in with a 103 temperature and every single joint in my body hurt,” he said. “I can’t describe how badly I felt. I was very sick. I was septic.”

Seven years earlier, he had been suffering from congestive heart failure and had a bicuspid aortic valve replaced by one made of a cow’s pericardial tissue. It had worked well until it had become so severely infected that – as he said his surgeon, Dr. Peter Pavlina, later told him – it looked “like chewed gum.”

Early the next morning after Pavilna’s warning, Colavincenzo underwent a 12-hour surgery. Six of those hours he was on a bypass heart and lung machine and soon he was struggling.

“I’m told they sent word out three different times to my family that it didn’t look good,” Colavincenzo quietly recounted the other day. “They said ‘He’s not doing well.’”

Pavlina replaced the infected valve with one from a 21-year-old female gunshot victim from Oklahoma.

But after Pavlina finished the marathon procedure, Colavincenzo said the surgeon told his family he feared (Colavincezo) might have had a stroke: “He said, ‘If he wakes up, I’m afraid he won’t be the same Paul.’”

Pavlina certainly had the last part right, but not how you would expect.

Colavincenzo said he woke up a 3 a.m. and though his chest hurt, he immediately felt better.

Still there would be severe problems down the road. A complication from the infection was a septic embolus to the right popliteal artery in his knee. That required multiple surgeries to treat.

Later, the knee was infected by the same bacteria that had laid siege to his heart and he had knee replacement surgery at the Cleveland Clinic. A month later the infection returned and he had another replacement surgery at Kettering.

He required extensive plastic surgery reconstruction and over the next two years he was continual pain. Although he used a cane, he still had trouble moving around. He had such intense night sweats, he would soak the bed.

“I had 40, maybe 44, hyperbaric oxygen treatments where I wore a space suit for an hour each time,” he said shaking his head. “I didn’t like those.”

He ended up at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota where a nasty, tough-to-treat fungus was discovered in the knee.

Finally, it was decided he could best survive with an above-the-knee amputation.

That surgery was January 17, 2020.

That’s two years ago Monday.

And yet the time frame that’s more important to him is this past week.

That’s when you saw that Pavlina was right.

Colavincenzo is not “the same Paul.”

He’s better:

»For the first time in six years, he is skiing again. His wife Teresa said he was scheduled to return to their Kettering home Saturday night from six days in Durango, Colorado, where he took part in a ski school that’s run by the non-profit Adaptive Sports Association.

»In March, Paul and Teresa, along with his son Joe, his 88-year-old father, Raymond, and some high school buddies will head to Montana on a ski trip.

»A month later, as part of a relay team effort competing in the Oceanside Ironman in California, he’s scheduled to swim the 1.2 mile leg of the event.

»And then in June comes the big test. He’s competing in the grueling Escape from Alcatraz Triathlon. Although he’s done the event three times before – all after his first heart valve replacement in 2009 – he’s been unable to do any sports ventures in recent years.

Now “The Doc versus The Rock” – as his first Alcatraz challenge was dubbed – comes with far greater challenges than before.

He’ll be competing with no prosthesis in the 1.5 mile swim through the treacherous currents of San Francisco Bay.

He’ll then use two different prosthetic legs for the 18 miles of biking through the hills of San Francisco and the 8-mile run that includes going up a daunting 400-step sand ladder, which is actually a large dune with 400 sand-covered railroad ties that he said he’ll be forced to hop using just one leg.

As her husband talked about this challenge recently, Teresa said his San Diego-based prosthetist, Peter Harsch – an Ironman competitor himself who has worked with combat casualties at the Naval Medical Center San Diego – tried tempering the lofty goals and suggested: “Maybe you should do a relay and just start with the swim.” Teresa smiled and shook her head: “When Peter walked away, Paul looked at me and said “I’m doing it! I don’t care if it’s 11 o’clock, I’m crossing the finish line!”

She said her husband’s remarkable recovery and renewed drive from one sports venture to the next prompted her cousin to sum it up for everybody recently and say:

“You could make a movie out of this.”

‘A godsend’

After his amputation Colavincenzo didn’t focus on what he’d lost as much as he did just wanting to get his prosthesis and go after everything life had to offer.

He and Teresa married two years ago and together they have six grown children from their previous marriages.

Colavincenzo also has a grandson now – 22-month old Anthony Paul.

“He’s cute as can be, he looks like me,” Colavincenzo said with a grin.

“He doesn’t look as much like you now,” Teresa cracked. “Not since he got hair.”

About the time the baby was born, Colavincenzo got his first prosthesis from a Minnesota company and he struggled with the adjustments.

“He wanted to ride his bike and there were times the leg fell off,” Teresa said. “Other times he rode without it and a few times he fell.”

But this past October, everything changed thanks to a discovery by Teresa that was pure happenstance.

They had gone to San Diego for a medical conference and before Paul headed out the door early one morning, she was telling him about some of the activities she’d been doing, including bicycling.

“As he was walking out, he looked at me and said, ‘I wish I could do that,’” Teresa remembered. “It made me sad.”

She began to tear up as she replayed the moment:

“I get emotional about it sometimes, but he has all these dreams, all these things that just made him happy and he hadn’t been able to do them. I thought to myself, ‘Why can’t my husband do these things? There’s got to be someplace in the world that can help him.’

“And I swear, it wasn’t five minutes after he went out the door, there was a piece on TV about the Challenged Athletes Foundation and how it helped people.

“I did some quick research and, believe it or not, found out it was located right there in San Diego.

“I immediately emailed them and they responded and invited us to come visit their place at 2 that afternoon.

“Paul and I had planned to go to the zoo that day as part of his birthday, but I told him there was a change. I didn’t tell him where we were going. That was a surprise.”

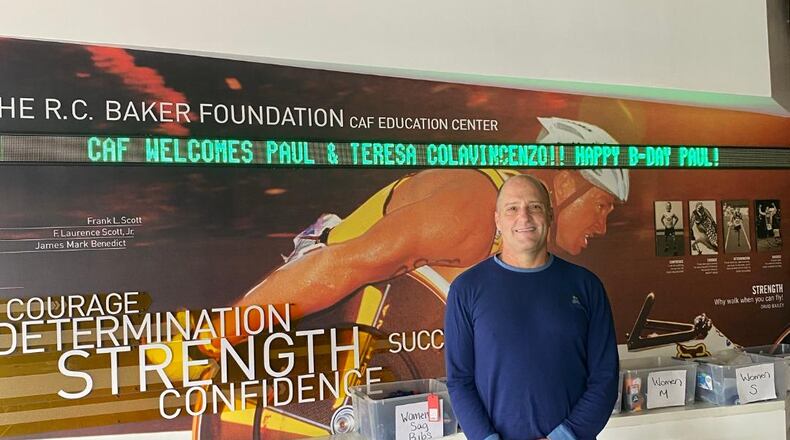

And they both were stunned when they walked into the Foundation and were greeted by an electronic banner that read: “CAF Welcomes Paul and Teresa Colavincenzo!! Happy B-Day Paul!”

The Challenged Athletes Foundation is a 25-year old organization that supports people with physical challenges so they can lead active lifestyles and compete in athletic events.

One branch of CAF – called Operation Rebound – runs programs for military veterans and first responders with permanent physical disabilities.

Colavincenzo is a Navy veteran of the first Gulf War. He was part of a 225-person surgical unit camped in the Saudi Arabian desert, 20 miles from the Kuwait border.

The CAF became an invaluable resource for Colavincenzo – “a godsend,’ he called it – and along with boosting his confidence and outlook, it made him aware of the myriad possibilities that awaited him.

Through the organization he connected with Harsch and he met other vets, including Daniel Riley, a U.S. Marine who lost both legs and three fingers in an IED explosion in Afghanistan – after he first served in Iraq – and now, through his involvements with CAF, is an accomplished skier, snowboarder and surfer.

It was Riley who heard Colavincenzo talking about taking an upcoming ski trip. When he got a private moment with Teresa, he stressed that she first get him involved in the adaptive ski school so he’d know how to ski again and not end up disappointed because he was ill-prepared.

That’s what these past six days in Durango were about and Teresa said her husband told her it was a great trip.

She said he was introduced to three different ways to ski—with his prosthesis on, with it off and ski fixtures added to his poles and with a bicycle frame that is minus the pedals and has two skis rather than two wheels.

“He admitted to me that if he hadn’t gone to this, he wouldn’t have been able to ski on our trip and would have ended up sitting in the lodge,” she said.

Colavincenzo said another birthday gift Teresa got him was to set him up with training sessions from noted triathlon coach Sergio Borges, who is also located in Colorado.

To help Colavincenzo with his preparation for the Escape from Alcatraz, he sends him weekly workout schedules and they talk often.

Although he said he hasn’t run since 2015, Colavincenzo said he’s up for the challenge:

“I wouldn’t just say it if I didn’t think I could do it.”

Lead by example

When we spoke at his home last Sunday, Colavincezo had just come from a swim workout at the Kettering YMCA.

He recently returned from San Diego with a new prosthesis, one fitted with a J-shaped, carbon fiber Cheetah Flex foot similar to the one two-time Paralympic triathlon medalist and world champion Grace Norman of Cedarville University wears.

He hasn’t gotten used to that leg yet. The one he was wearing the other day – which had a U.S. Navy decal affixed like a big tattoo to the thigh part – can be adjusted to nine levels of flexibility through an app he has on his phone.

As he learns all the new ways to navigate the world, he said there are certain qualifiers he does not like at all:

“I don’t like to say handicapped or challenged. I’m just trying to make the best of what my body can give me.”

Teresa, who is a special education teacher, chimed in:

“Here’s a little disability etiquette. I had a professor who would take off if we ended anything in ‘-ed.’ So if you said ‘handicapped, disabled, challenged’ you lost (grade) points.

“You have a disability, you’re not disabled. You have a handicapping situation, but you are not handicapped.”

Colavincenzo admitted: “Look, I know I’m lucky to be alive. My doctor was surprised I survived. “And one thing I’ve come to realize, whether you admit it in life or not, if you have loved ones – with me, especially, it’s my kids – but really any people who know you, they look at you and see how you deal with something.

“I try to put on a good face and just do the best I can. Your examples are better than just your talking. And it you think way beyond that, it’s what your legacy is going to be when you’re not round.”

Speaking of not being round, Colavincenzo had noted that the day he was doing his April triathlon swim in California was the same day Teresa was throwing a baby shower for her daughter Kayla, who is expecting a son in June.

So he said he wouldn’t be here for it.

“But I changed the date of the shower,” Teresa laughed. “So even though it’s just for the girls, it’s at our house. He’ll be here.”

Then again, he did say he wanted to go after everything life had to offer.

About the Author