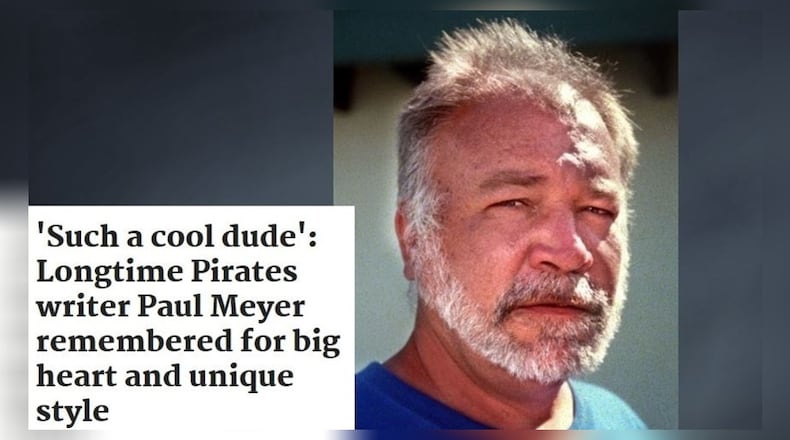

Meyer, 73, passed away this week, and it hit me like one of his pointed jabs because he was a maestro at putting people in their places when they needed it.

And the recipient always laughed because Meyer was so respected and most were honored that he took the time to aim barbs their way.

Meyer and I traveled together, usually sitting in the back of airplanes, he smoking cigarettes and me puffing mini-cigars because you could smoke on flights in those days.

By the time the flight landed, my side would hurt from laughing so much. If you spent any time with Meyer, you were going to laugh until your insides screamed, “No more, no more.”

When the Dayton papers merged in the mid-1980s and became one, Meyer and I split the beat and split the travel. Neither of us was happy about it and Meyer moved to Pittsburgh, where he spent the rest of his career covering the Pirates for the Post-Gazette.

As close as we were, we were fierce competitors. Neither one of us wanted to get beat on a story. In all my years, Meyer was the toughest competition I had.

He was a dogged reporter and a smooth and quick writer. The Journal Herald was a morning paper with deadlines close to when games ended. Meyer not only never missed a deadline, his copy was clean, written well and accurate. Meyer was a stickler for accuracy. He wasn’t afraid to criticize, but he always did it fairly. Managers and players respected him.

Roll it all together and you have a total professional package that was Paul Meyer.

On the outside, Meyer was gruff and abrasive, quick with a quip to put somebody in his or her place, usually a humorous jab that broke up the press box.

The more he liked you, the more he made fun of any foibles, all in good fun. And the recipient laughed harder than anybody. He was the only person I knew who could get the last word in on Hall of Fame broadcaster Marty Brennaman and leave him laughing.

On the inside, Meyer was soft and caring. He was particularly adept at helping young journalists find their way and at doing anything to assist out-of-town writers.

Meyer had a way of phrasing questions that no other writer would dare ask. Legendary pitcher Tom Browning was not a great quote, win or lose.

After Browning pitched a particularly good game one night, Meyer approached Browning and said, “Are you going to give us some good quotes or are you going to say the same ol’ crap?”

Former Reds manager John McNamara and Meyer were particularly close, probably because they were two of a kind. Neither hesitated to say what they thought and let the adjectives hit the floor.

During the 1982 season, the Reds were on their way to a 101-loss season. As the defeats mounted, McNamara kept defending the team night after night.

Finally, after one bad defeat, Meyer walked into McNamara’s office and before anybody could say anything, Meyer said, “Are you going to tell us the truth tonight about how you feel about this bad team, because you know you’re going to get fired.”

Three days later McNamara was terminated.

Meyer’s work clothes were not stylish, it was not something he cared about. Nearly every game he showed up in shorts, a T-shirt and sneakers. In the off-season, Meyer covered the Wright State University basketball team.

Somebody connected with the team gave him a pair of white and green WSU game shoes and he wore them for the next several years. And most of his T-shirts were given to him and he liked to say, “If it’s free, it’s me.”

Brennaman liked to ask him, “Hey, Paul, did you dress in a dark closet again today?”

In Meyer’s case, clothes certainly didn’t make the man. But what was under those clothes was an unforgettable character beloved by everybody with whom he came in contact.

Pittsburgh broadcaster Greg Brown described Meyer perfectly.

“He played this curmudgeonly role, but he was really a romantic about the game and life,” said Brown. “He commanded respect because he was so good and so fair and he knew the game. Such a cool dude.”

Perfect. Indeed, Paul Meyer was such a cool dude. Rest in peace, old friend, rest in peace.

About the Author