“They try to pull the best of the best from whatever state,” he said. “You look at the roster and see these kids were high school All-Americans. You question if you’ll make it, but it’s a matter of believing if you practice and put in the time and do the best you can do, it will materialize for you. It materialized for me.”

MORE COLLEGE FOOTBALL

• Buckeyes’ Barrett defends accuracy

• Top 7 players in Wittenberg history

• Landers relives touchdown that didn't count

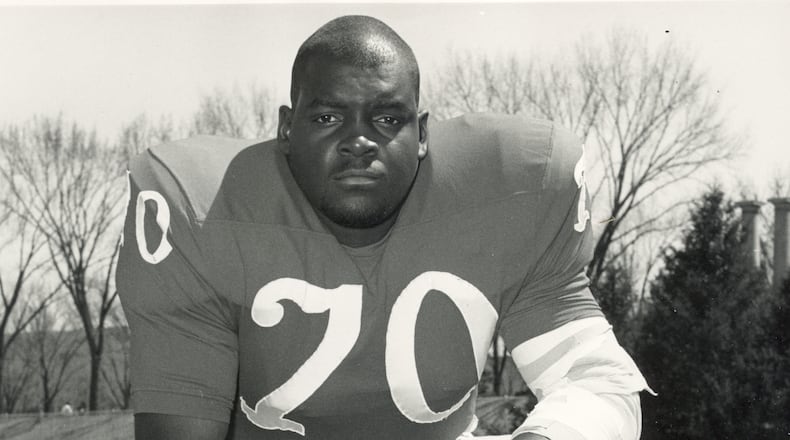

Freshmen weren’t eligible then, and McGhee played sparingly as a sophomore and only slightly more as a junior. But the longtime Urbana resident not only cracked the starting lineup as a senior, but he became a first-team All-Big Eight selection at right guard and helped the Cornhuskers to an 11-0-1 record and their first national title in 1970.

He’ll be inducted with four other players into the Nebraska Football Hall of Fame during the weekend of the Northern Illinois game Sept. 16.

The 69-year-old great-grandfather was caught off guard when he was notified of the honor by mail.

“It was a shock, but a very pleasant shock,” he said.

The recognition is long overdue, according to 1972 Heisman Trophy winner Johnny Rodgers. He ran behind McGhee as a sophomore and gained 929 yards rushing and receiving and averaged 11.9 yards per touch. Two years later when he won the Heisman, he had 1,361 yards and a 10.4 average.

“We called him ‘The Floater.’ He’d float like a butterfly and sting like a bee — just like Muhammad Ali,” Rodgers said. “We used him to pull a lot because he was very mobile, but he was stocky and strong.

“We didn’t have guys who were pro-sized as linemen. We had guys who were mid-sized and scrappers, and Donnie was definitely a scrapper and covered some ground. I just followed his lead and cut off his block — because you knew there was going to be a block.”

POPULAR ON SNS.COM

• Top 7 players in Kenton Ridge history

• Top 7 players in Springfield North history

The 1970 title was unexpected. The Cornhuskers under legendary coach Bob Devaney started the year No. 9 and tied third-ranked Southern Cal in a non-conference game. They beat their next eight foes by at least two touchdowns, but they had a tussle in the regular-season finale with rival Oklahoma, winning at home 28-21.

The Huskers were ranked No. 3 when they faced LSU in the Orange Bowl behind No. 1 Texas and second-ranked Ohio State. The help they needed to vault to the top spot came when the Longhorns and Buckeyes lost their bowl games earlier that day.

“We said going into our game, ‘There’s no way in the world when we beat LSU — not if, but when — that we’re not going to be national champions.’ Even coach Devaney said that,” McGhee said.

The Cornhuskers prevailed, 17-12, to finish No. 1 in the Associated Press poll.

“This may seem like a cliché, but we had camaraderie,” McGhee said. “We were a team that cared about one another.”

They also had players willing to do whatever it took to improve — McGhee included. He was 305 pounds when he first weighed in as a freshman. That may be ideal size for an interior lineman today, but it was considered too beefy then. By the time Thanksgiving break arrived, he was a svelte 250.

“They ran me, they worked me, they exercised it off,” McGee said. “My playing weight from that point on was about 260 or 265.

“It was a tremendous help. I thought I was decent as far as linemen in my high school days. But the competition level exponentially goes up. Taking the weight off allowed me to have quicker feet. Getting in the weight room allowed me to get stronger. I had a whole different outlook on how to play ball.”

Devaney once worked on Duffy Daugherty’s staff at Michigan State and cultivated recruiting ties in the Saginaw Valley area in Michigan. He kept it going after taking over at Nebraska, which is how McGhee ended up so far from home.

After graduating in 1971, he returned to Flint for one year as a school teacher and then took a job with General Motors there. He migrated to Dayton and worked for GM as a negotiator with labor unions. After quitting that position in 1987, he took a job with Honda and retired in 2008 after 20 years in management at the Marysville plant.

McGhee, who was inducted into the Greater Flint African-American Sports Hall of Fame in 2009, hasn’t been back to a Nebraska game since before Devaney’s death in 1997. He’ll be joined at the ceremony by wife Ruby and one of their two children, son Roland, who is bringing his family.

Rodgers plans to be there, too.

“I’m looking forward to spending some special time with him on that day,” Rodgers said. “He was one of the best. He definitely deserves it.”

About the Author